Azadi Tower

Some parts of this article have been translated using Google’s translation engine. We understand the quality of this translation is not excellent and we are working to replace these with high quality human translations.

Some parts of this article have been translated using Google’s translation engine. We understand the quality of this translation is not excellent and we are working to replace these with high quality human translations.

Introduction

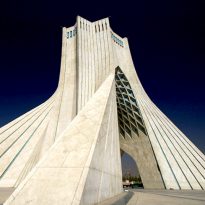

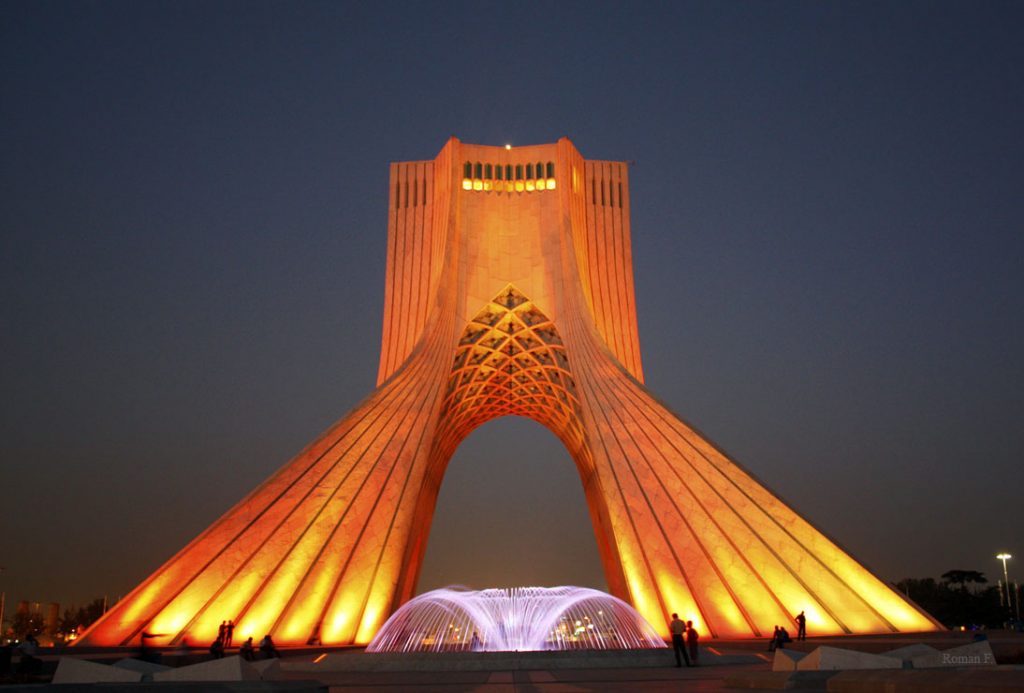

The Tower of Azadi, formally Shahyad Tower, with an inverted Y-shaped structure was built in 1971 and inaugurated on October 16 of that year, although open to the public on January 14, 1972. Designed by the architect Hossein Amanat, combines Artfully modern architecture with traditional Iranian influences, especially the “iwan” style of the arch which is lined with 8000 pieces of white marble.

The monument was commissioned by Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran to commemorate the 2500th anniversary of the first Persian empire. The project was funded by 500 Iranian industrialists. The word Azadi means “libretad” in Persian.

Location

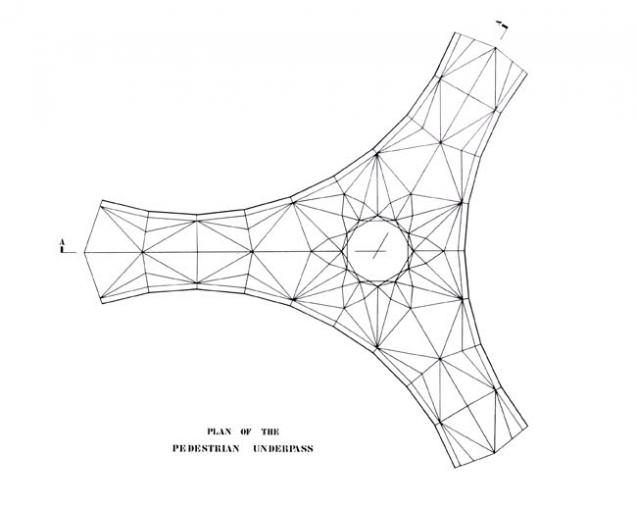

The Tower is one of the visual icons of Tehran. Located in the 10th District of Iran’s capital (خیابان آزادی, پل عابر), it rises above a large oval park, Azadi Square, scene of numerous protests during the 1979 revolution and today focal point for demonstrations. The monument marks the west entrance to the city, a few kilometers from the airport.

Concept

Hossein Amanat based his ideas combined post-Islamic Iranian architecture with that of the Sassanid and Achaemenid eras. During the 1960s due to the Sha White Revolution, Iran became a major exporter of oil. The Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi reinvested the profits in the implementation of programs to modernize the country. The architect named this movement as a “mini rebirth”.

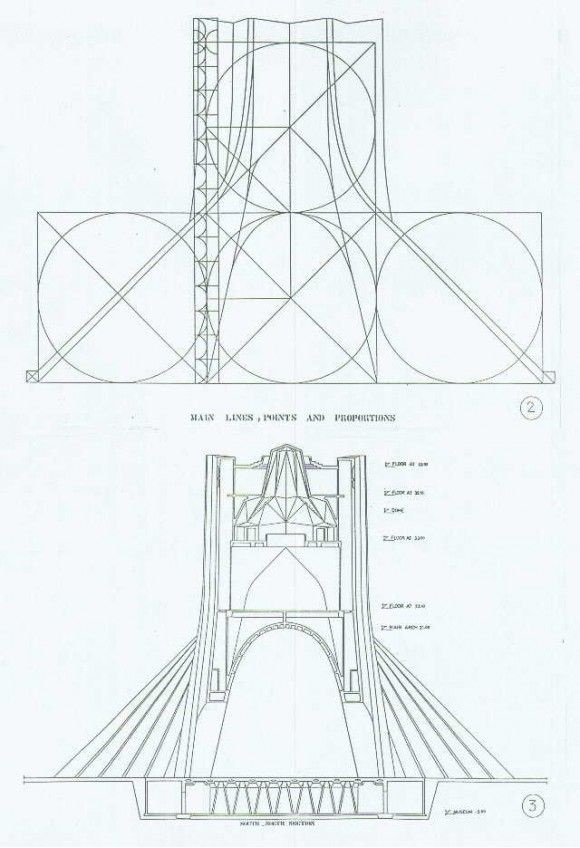

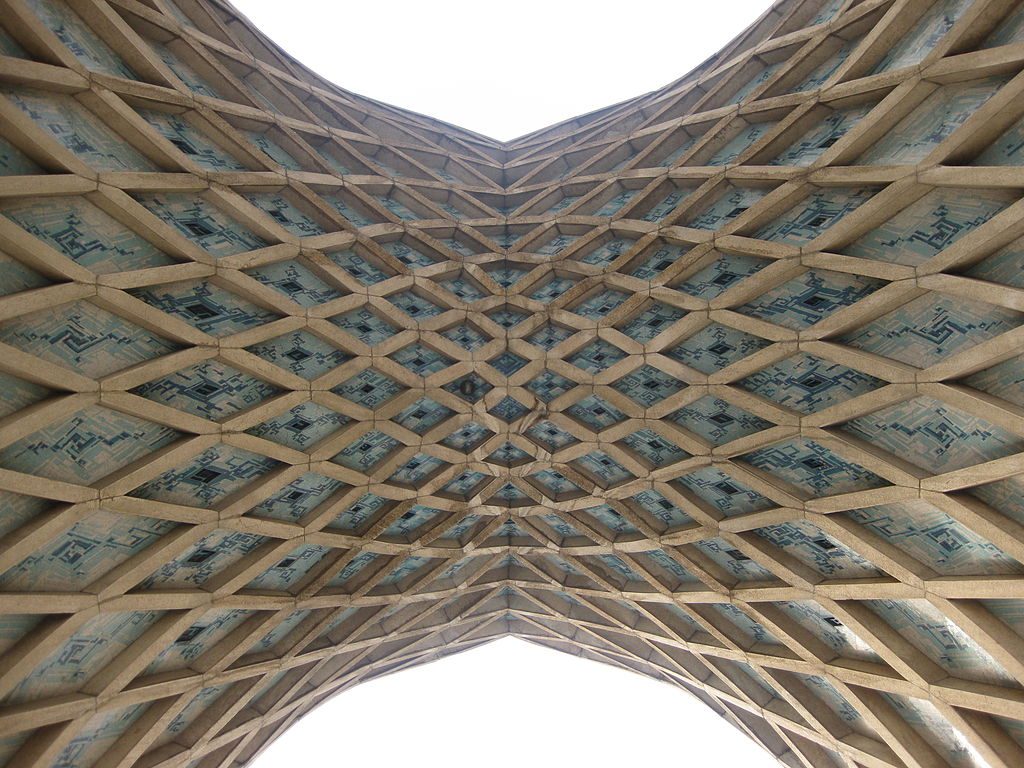

In an interview Amanat explained that the building starts at the base and rises skyward, so its design was inspired by the feeling that Iran should be moving to a higher level, describing each section of the tower and what had influenced his design. The main vault is a Sasanid arch representing the pre-Islamic period. The broken arch above it represents the Islamic period, as it became a popular form of arch after Islam began to influence architecture. The “net of ribs,” which connects the arches to each other, shows the connection between pre-Islamic Islam and post-Islamic Islam.

It is alleged that Amanat also integrated a degree of Bahai symbolism into the design. There are exactly nine stripes on each side of the tower and exactly nine windows on the high sides of the building, with nine being a significant number in the Bahai faith.

Spaces

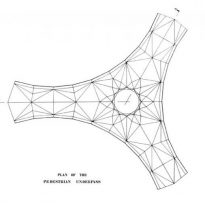

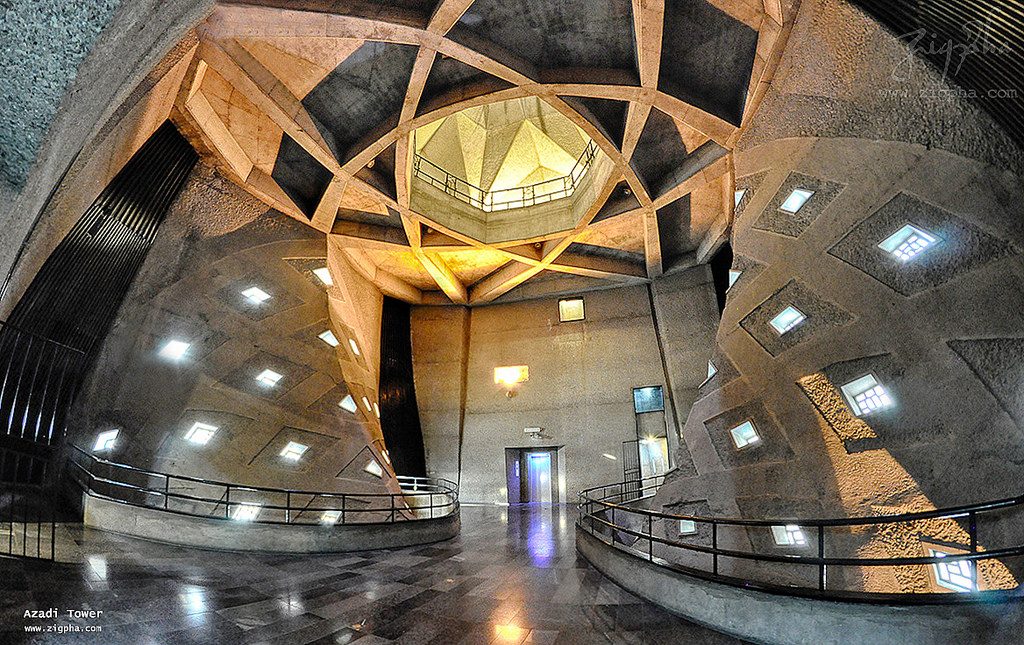

The tower is part of the Azadi Cultural Complex, in an area of approximately 68,000 m². There are several fountains around the base of the tower and an underground museum, as well as multiple galleries, libraries and souvenir shops distributed at different levels of the tower.

The building has three floors with a height of 5m, four elevators and two stairs with 286 steps. By stairs or elevator visitors can access the highest part of the tower where a viewpoint is located. At the base there are exhibition galleries and a coffee shop. However, all major entrances sink underground to improve the circulation flow of the complex.

Square

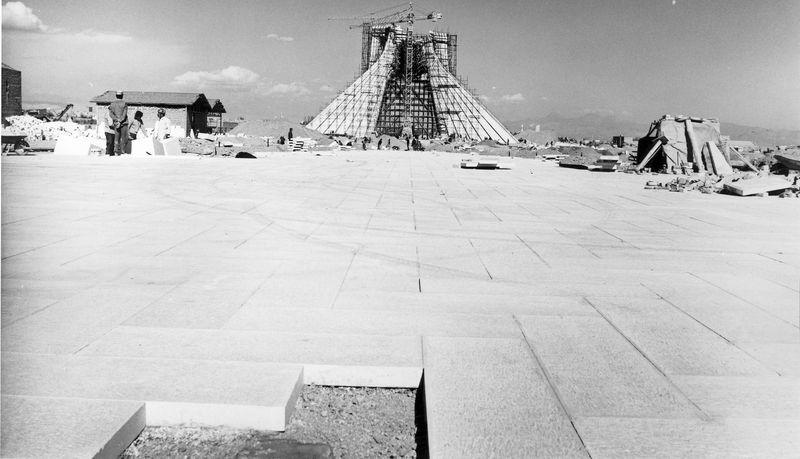

The square is almost oval. Along the east-west axis the diameter is 380m and in the north-south axis of 210m.

Amanat used the circulating arteries of the existing urban context as directional vectors to influence the monocentric landscape pattern of the tower complex. The square contains fountains and landscaping in patterns similar to traditional Persian gardens.

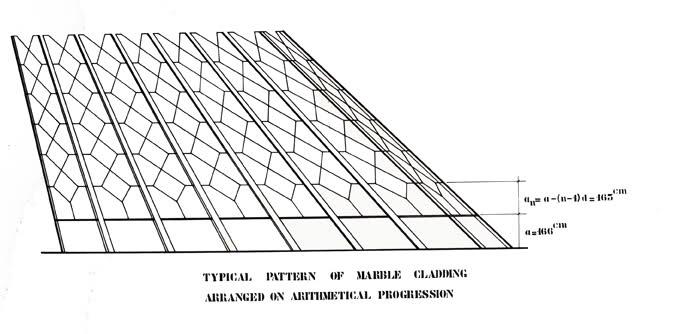

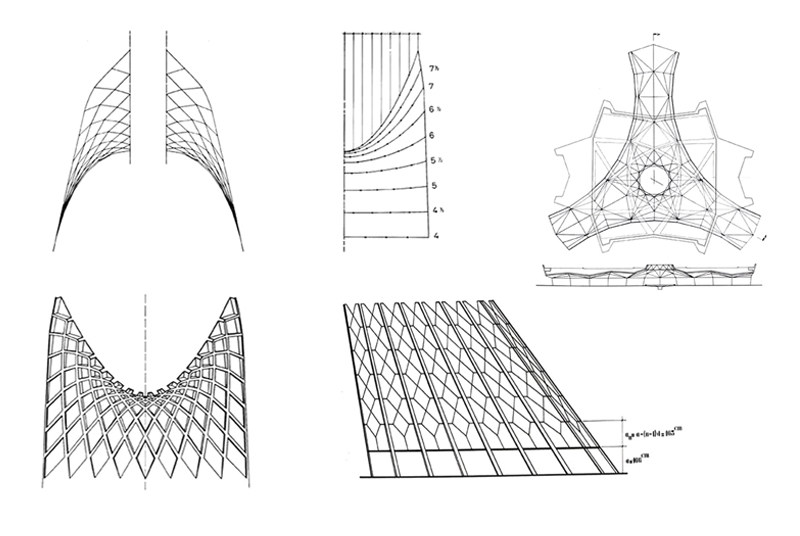

The circulation trajectories, as well as a ripple effect, influenced the differentiation of the scale and the articulation of the marble blocks in the body of the tower.

Museum

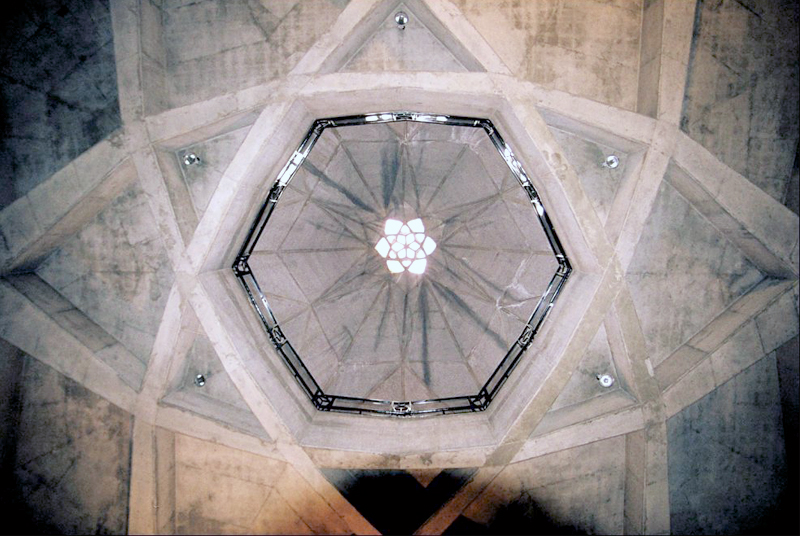

Below the main vault is the access to the tower that leads to the Azadi Museum in the basement. With a dim lighting, the strategically located showcases store unique pieces of great value, gold and enamel, painted ceramics or marble, making even more noticeable the deliberately austere atmosphere of the building, with stone walls, dark floors, pure and sober lines and proportions Measured. A concrete mesh forms the ceiling of this closed room with heavy doors.

The main showcase is occupied by a copy of Cyrus Cylinder, the original is in the British Museum. A translation of the cuneiform inscription of the cylinder is inscribed in golden letters on the wall of one of the galleries leading to the audiovisual department of the museum. Opposite, a similar plaque lists the Twelve Points of the White Revolution. Next to the Cyrus Cylinder, a gold plaque commemorates the original presentation of the museum to Mohammad Reza Pahlavi by the Mayor of Tehran. Other elements exposed are square slabs, gold leaves and terracotta tiles of Susa, covered with cuneiform characters.

A mechanical conveyor allows visitors to see the corridor in comfort. Some art galleries and halls have been assigned to temporary fairs and exhibitions

Structure

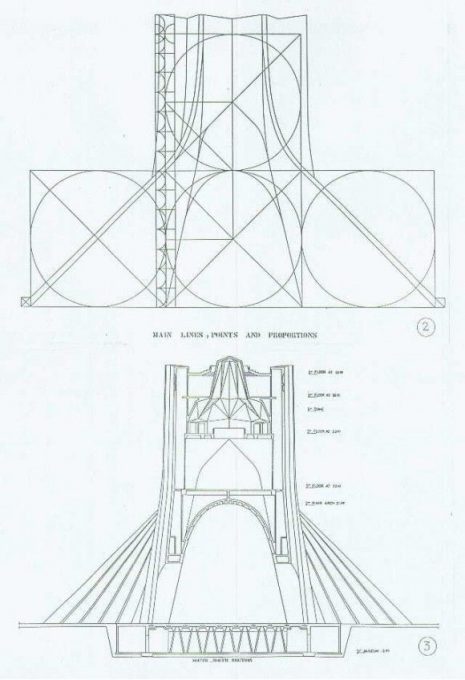

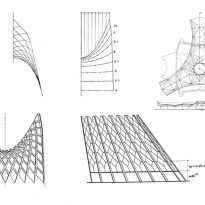

Like many other architects in 1960, Hossein Amanat was very interested in the structural performance of the geometric modules. It combined the organizational logic of a monocentric Islamic pattern with the forgotten traditional Persian stone block architecture as well as articulated landscape divisions. The architecture of the Azadi Tower complex is the result of both its heritage and its modern influences and the future vision of the city.

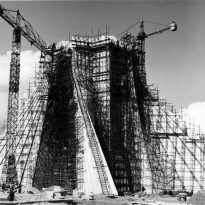

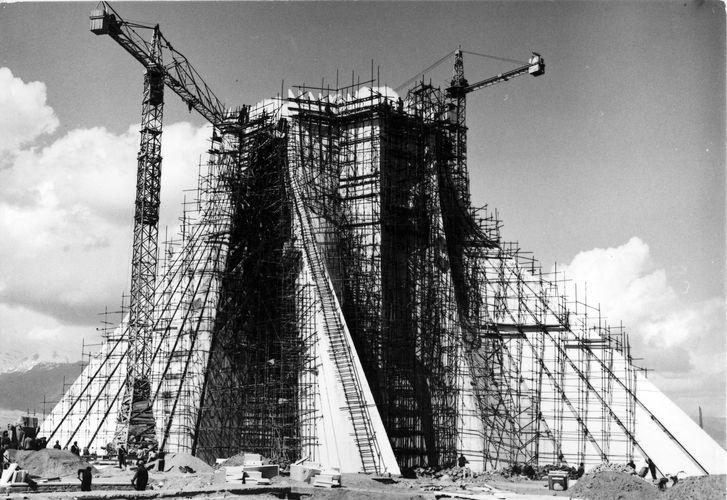

Amanat was impressed by the work of the engineers of the British firm Ove Arup & Partners, especially in the construction of the Sydney Opera House, which led him to hire them for the structural design of the Tower. This decision led to clashes with the country’s bureaucracy as well as with several conservative and nationalist engineers. In spite of the resistance, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, like the Empress Farah Pahlavi, took the side of Amanat, sending a letter to Bousherhri, head of the Celebration Council, telling him to allow the architect to go ahead with his project .

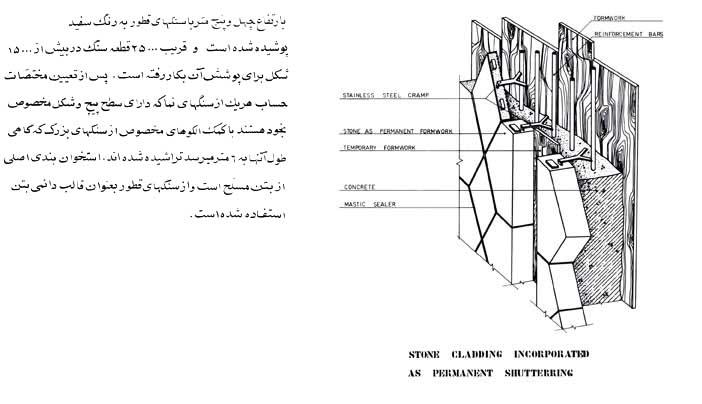

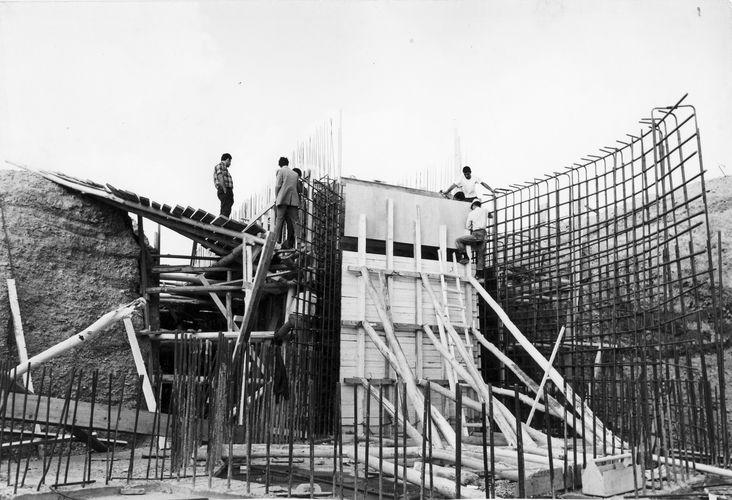

The monument was built with concrete poured in situ with solid marble as formwork and cladding.

Base

Its broad base narrows as it ascends towards a tall arch, densely interwoven with lines of ribs which in turn is the bottom of the robust and beveled tower that crowns the monument. A complex structural engineering forms the skeleton of the tower that depends from the angle you look at offers different geometries, wide and wide on one side, tall and thin on the other. The stone surfaces curl and flow like a dance dress, and its formal complexity suggests something both deeply ancient and firmly modernist.

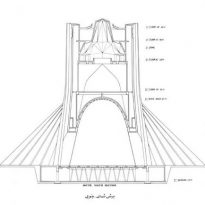

The bases were developed on a rectangular surface of 42x63m, acquiring a twisted form to provide greater stability to the arc that unfolds on them, formed by the union of the same. The elliptical arch is 21 meters above the ground and consists of eight other sections that reflect the evolution of the elliptical arc in twill arch. In the interior of two of the bases are located the elevators and in the other two the stairs.

Tower

The structures of the body of the tower, which start at the top of the four bases and the covers forming the dome grid, are inspired by the Seljuks and Ghaznavids dynasties (seventh century AD)

Seen above, the plane of the Tower shows an octagonal form with curves in the sides that overload the structure, representing the “good taste” of the art of architecture that combines octagonal forms with the oval forms of the square, responding to an appropriate Visual communication of the whole set.

Materials

The main core of the building is reinforced concrete, together with the Iranian rocks and materials used in its construction, such as the 25,000 blocks of 6m long white stone from the Joshaghan Isfahan quarries with 15,000 different forms and complex surfaces that were used On the facade. The computerized system to define the fabric of the complex surfaces was a technological advance in the architecture of the country. The continuity achieved by careful calculation of each piece has given the tower the nickname “the tower covered with silk”. The articulation of custom marble units for the facade translates into fluid concrete forms that in turn create the inner shell of the body of the tower.

The main doors are made of Hamadan granite and its weight is approximately 7 tons. Soil stones and fountains were extracted from the Pearl Kurdistan mine.

The floors of the crypt that forms the museum are made with blocks of black marble.

The turquoise tiles and the peacock feather pattern that decorates the arches are the main symbol of the architecture of the Islamic period.