Zonnestraal Sanatorium

Introduction

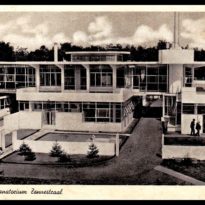

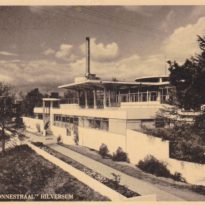

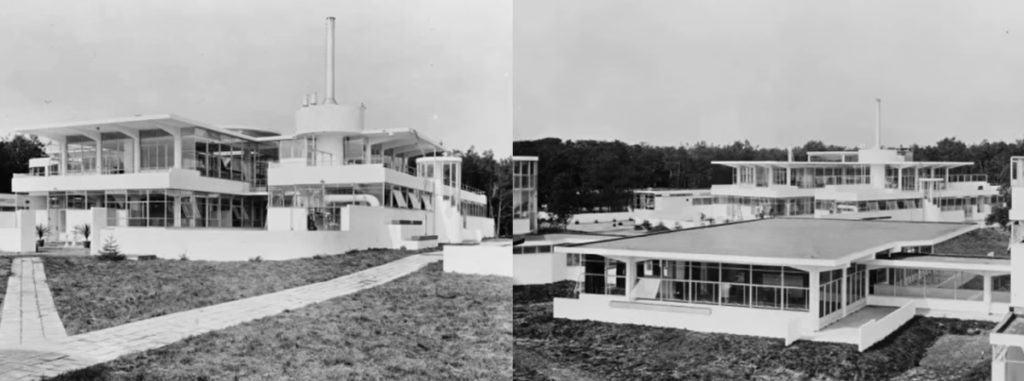

The Zonnestraal Sanatorium is a jewel of the modern movement made of concrete and glass, revealing its own time and establishing itself as one of the most experimental designs within one of the most creative decades of modernism, between the two world wars.

Designed between 1925 – 1927 by the principal architect of the architectural movement within the Netherlands, Jan Duiker, together with the architect Bernard Bijvoet and the structural engineer Jan Gerko Wiebenga, began operating in 1928, was completed in 1931, and functioned as rehabilitation center for patients with tuberculosis.

Its construction was commissioned by the Dutch Diamond Workers’ Union for its workers who, breathing the air contaminated by dust particles in the polishing and profiling workshops of the stones, frequently suffered from respiratory conditions that used to lead to the development of tuberculosis.

Zonnestraal was celebrated as an important monument in the early years of the modern movement, even while it was under construction. The sanatorium was in operation from 1928 to 1950. In 1957 it became a general hospital, and since then several annexes have been added. The death of Duiker in 1935 and the progress in the eradication of tuberculosis after World War II, caused the sanatorium to deviate from public and academic attention, falling into disuse and disrepair, with sections that literally disappeared between the landscape surrounding. For almost two decades, the Zonnestraal Sanatorium was forgotten.

In the 1960s, however, the sanitarium was rediscovered and considered by historians of architecture as an important monument of modern architecture. In 1982, before the imminent deterioration of a building that serves as an example of modern architecture in the Netherlands, the Dutch government summoned leading architects, headed by Hubert-Jan Henket and Wessel de Jonge, for their recovery. In 1995 he received the category of building with Historical Protection. In 1997, a master plan was developed to convert it into a health center with a combination of medical and recreational functions.

Location

The sanatorium is located in the city of Hilversum, Holland, in Loosdrechtse Bos 7.

Concept

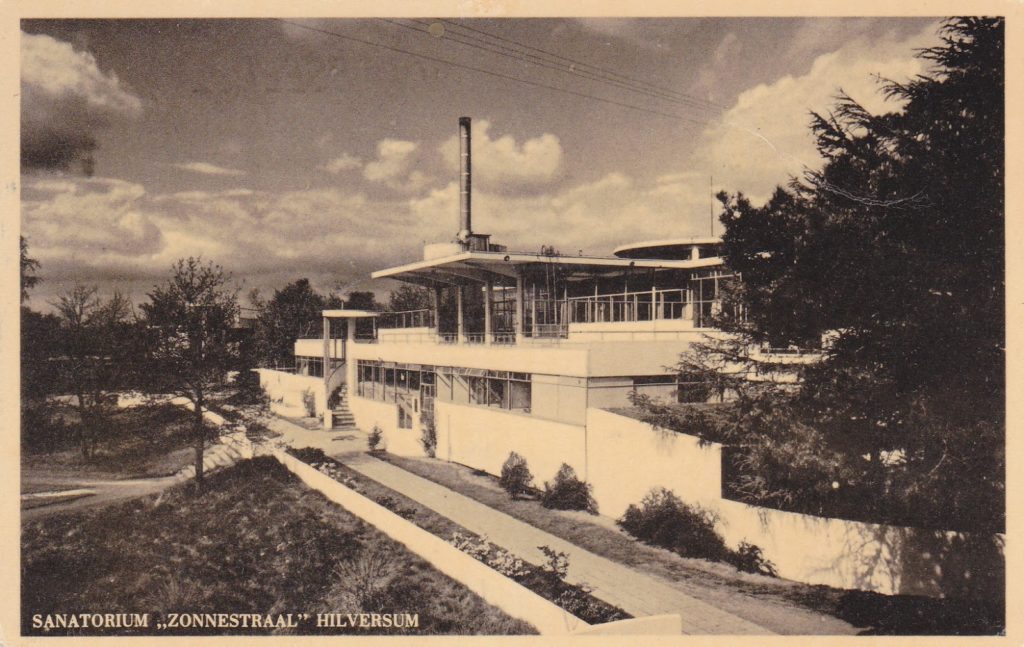

Embracing the progressive ideals of the modern movement, Zonnestraal’s architecture sought short-term functionality, providing the necessary lighting and ventilation that specialists postulated were necessary to treat the disease. The idea was to create a building that offered patients lots of fresh air and light.

The ensemble is known as the great example of the “Nieuwe Bouwen” movement, a modern Dutch movement. One of the aspects associated with this movement is the idea of disposable buildings: the requirements for the use of a building are linked to a short life. After all, the building was built specifically for patients with tuberculosis and, because it was thought that the disease would be eradicated within the next 30 years, a functional life of 30-50 years was assumed for the sanatorium. For this reason the materials used in its construction were the standards and fair to comply with the regulations.

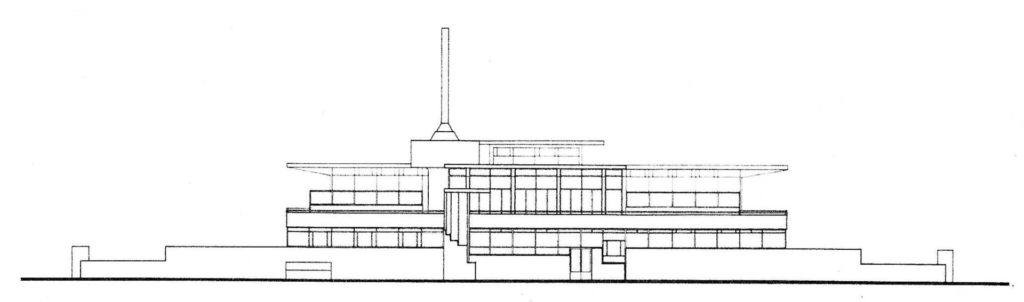

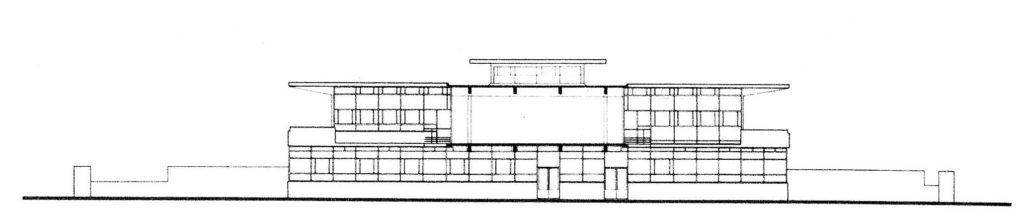

Zonnestraal is an indisputable pinnacle of modern Dutch architecture. Its glass skin wrapped around the slender structure, the elongated white facades, the cylindrical stairs and the fireplace combine to create an image of white ships in their moorings, the perfect metaphor for modern architecture.

Spaces

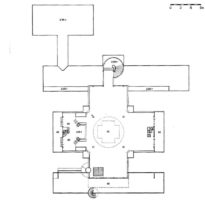

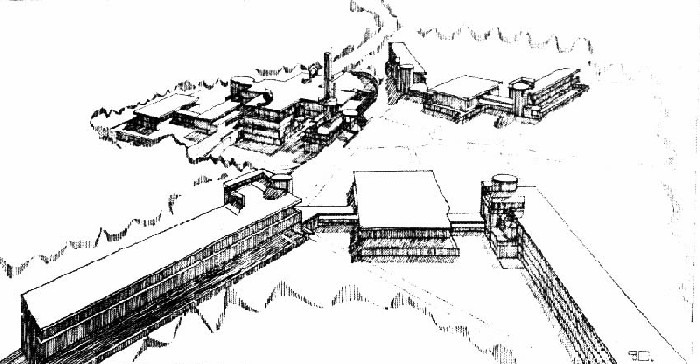

The original project raised a complex consisting of a main building and 4 pavilions, although 2 were never built, leaving in the main building, two pavilions, the Henri ter Meulen and the Dresselhuys, 5 workshops and the house for the staff.

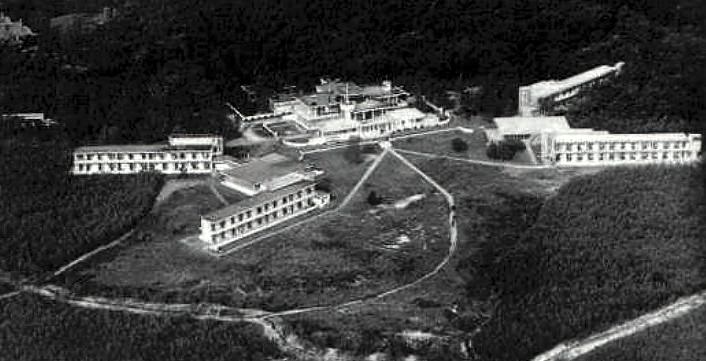

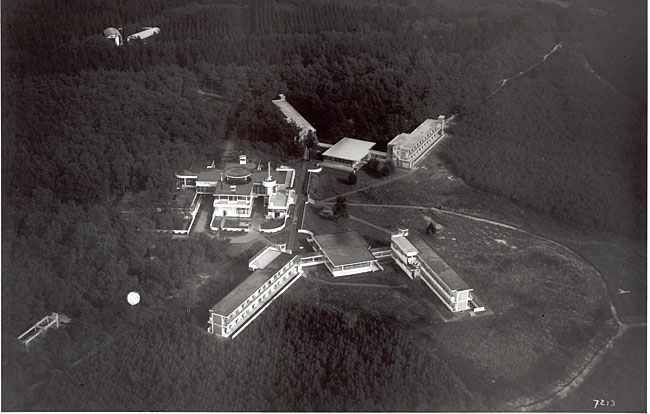

In the center of the 120-hectare site is the main building with the patient pavilions on both sides. The orientation and location of these three buildings were determined by the sun and an unobstructed view. The buildings accommodated 128 patients.

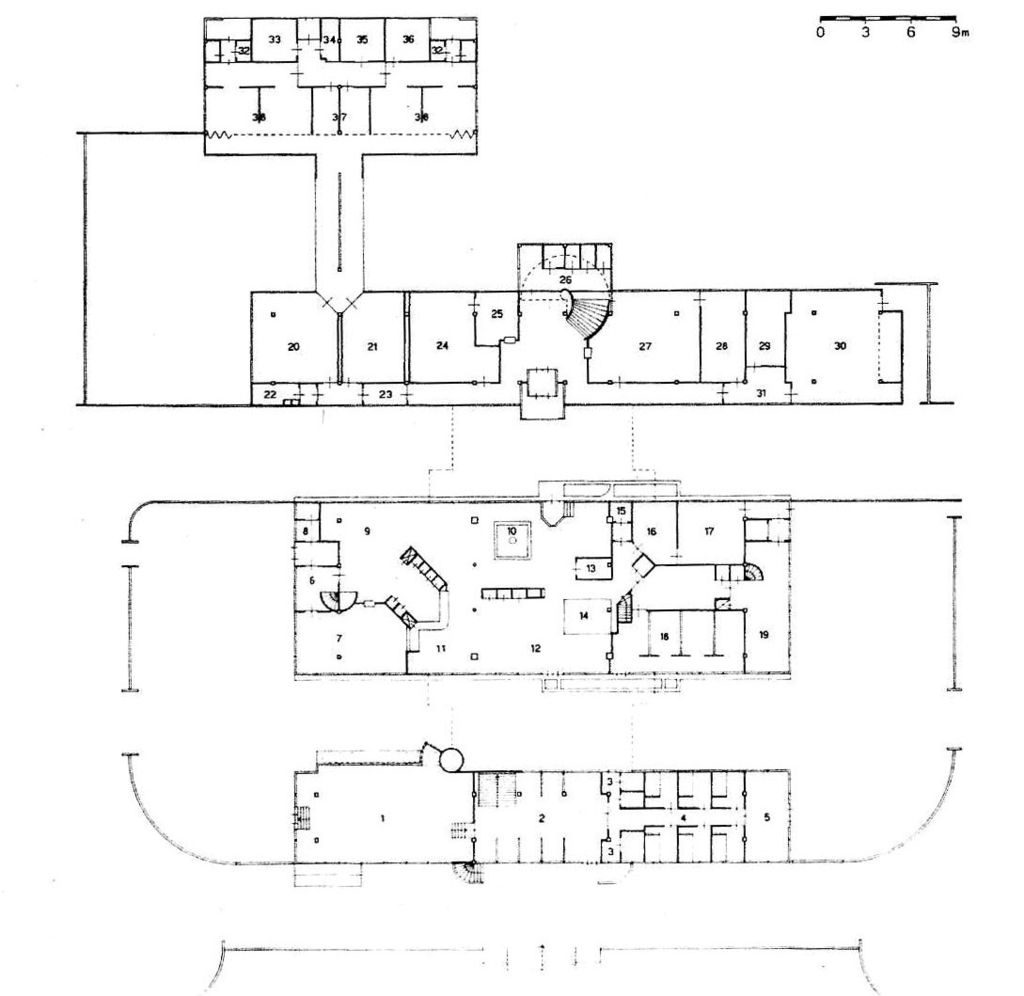

Main building

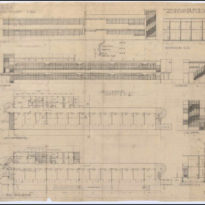

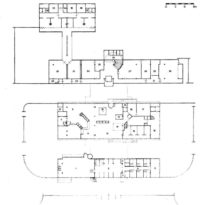

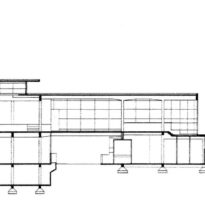

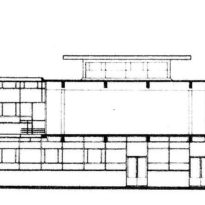

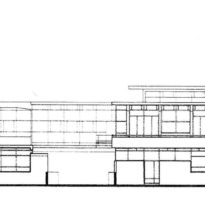

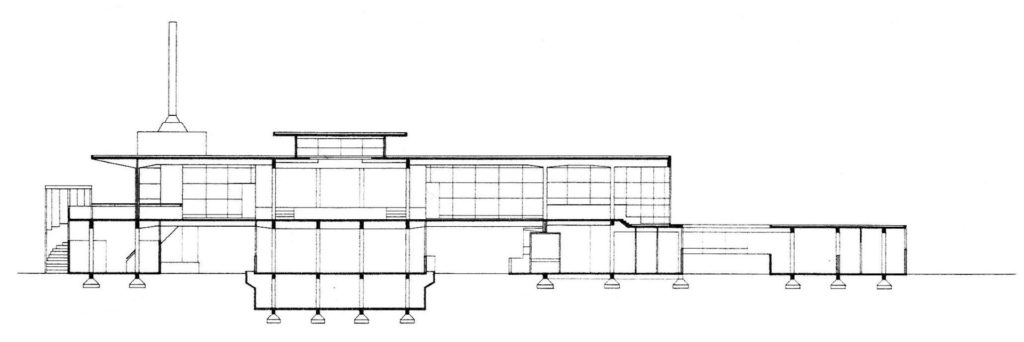

The main building consists of three elongated linear blocks, with the medical department and the entrance in the north block, kitchen and storage space in the central block and sanitary facilities and the boiler room in the south block. Placed on these three volumes there is a restaurant with a cruciform plan that purifies its geometry in relation to the rest of the building, adopting the shape of a Greek cross and which opens onto a roof terrace on the south block. The latter also contains the entrance for patients who come from the pavilions to the restaurant. The block also has a small extension for terminal patients. The entire building combines large white glass enclosures and cantilever slabs.

The entire floor of the building is generated from a 3x3m grid, following the principles of Le Corbusier‘s modular architecture.

Pavilions

The pavilions are located on the sides of the main building. Each pavilion is configured as a pair of two-story wings placed at an angle of 45 °, which gives them an unobstructed view of the surrounding forests and also plenty of sunlight.

The Henri ter Meulen Pavilion began to be built at the same time as the Main Building. The two wings are connected by a central volume that housed the general facilities and services. The patients had their own room, these were in groups of 12/13 per floor, with a total of 48 rooms, with wide spiral concrete stairs protected with large cylindrical windows.

The Dresselhuys Pavilion is the same as Henri ter Meulen, with an axis of symmetry that coincides with that of the main building. But its allocations were more adapted to progress and functionality and it was equipped with a chairlift while expanding the number of rooms, always on both sides of the common meeting room.

A little further away is the circular house of the “Koepel” service, where there were 16 small rooms for the staff.

Structure and Materials

The buildings are constructed with a concrete skeleton with extremely thin steel frames to accommodate the large windows. Extensive use of prefabricated elements was made and although concrete was relatively expensive in the 1930s, construction was carried out in the most economical way possible to meet the minimum requirements. The beams and the overhangs are narrow and thin in all the places where it was possible, with some concrete floors whose thickness was between 8-12cm. The architect himself saw the construction as a “disposable building” which he only predicted a use for 40 years.

The geometric structure of the complex can be clearly seen in the drawings that show a strict geometry, both in the axes that are present in particular in the main building, as in the measurement system. The smallest module is that of the rooms, 3x3m and the upper one consists of 12 of these rooms. These dimensions are related to the standards of the time: the formwork could be removed before with a maximum length of 3 meters. Another solution to save on construction.

In the main building the structure is made of reinforced concrete with longitudinal corners that rest on pillars every 9 meters. The cantilever floor slabs reach 1.5 m with cantilever beams. This counterweight helped minimize the use of concrete.

The facades are mainly glazed, with a steel frame, the vertical walls and those of the annexes are hollow constructions or plastered wire mesh.

The color scheme also gives buildings an airy appearance: white stucco with light blue-blue frames for the main building and yellow frames for workshops.

Video