Social Housing “Hufeisensiedlung”

Introduction

In 2008, UNESCO declared the Horseshoe (or Hufeisensiedlung) Project a World Heritage Site. It forms part of Bruno Taut‘s Britz Residential Project, as one of six social housing buildings designed in the modernist style of Berlin. The other five are: the Falkenberg Garden City in the district of Treptow (B.Taut, 1913-1916), the White City in Reinickendorf (Otto Rudolf Salvisberg, Wilhelm Büning and Bruno Ahrends, 1929-1931), the Carl Legien Project in Prenzlauer Berg (B.Taut, 1928-1930), Siemensstadt in Charlottenburg (H. Scharoun, W.Gropius and others, 1929-1934) and the Schillerpark Project in Wedding (B.Taut 1924-1930, extended between 1953 to 1957). In the 1990’s, the housing complex was restored.

History

As a result of the huge housing shortage which had plagued Germany since the end of the World War, numerous cooperatives, public associations and syndicates were created with the objective of building affordable homes in Berlin.

One of the largest associations created for this objective, the GEHAG, was founded in 1919 to build houses for its members. Committed to a progressive plan of modern houses, the association looked for the collaboration of new architects. In 1924, Bruno Taut was named as the chief architect of the project. Taut had been involved in the development of the large residential community, Gross-Siedlungen, whose concept was in the construction of large housing estates within garden-cities, as well as another similar project in Magdeburg between 1912 and 1915.

To build the new social housing, they looked for cheap land outside of Berlin but with good transport links to the city, this being the origin of Hufeisensiedlung. When the inhabitants of “central Berlin” saw the building, they began to complain, saying that such a beautiful thing should not have been created for the working classes.

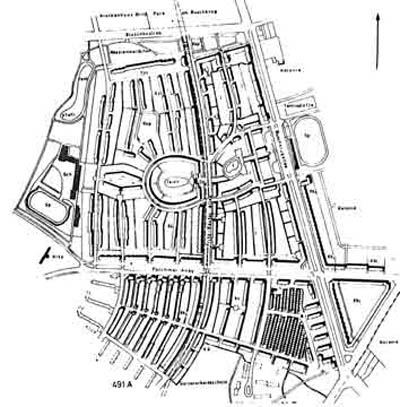

Location

The settlement was built in a zone to the South of the suburbs of Berlin, Britz Süd, in the district of Neukölln, Germany. It was one of the first “Gross-siedlung” (major settlements); housing collectives which were built in the area applying the concept of the garden city, and designed by a functionalist architect. It’s main access roads are found at Fritz-Reuter Allee 2/72 and Lowise-Reuter-Ring 1/47.

Concept

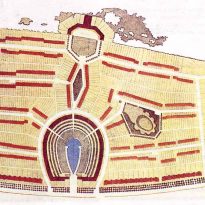

Taut‘s concept of the horseshoe-shaped building was derived from his desire to fulfil the needs of its inhabitants for socialisation. His intention was that the inhabitants of the estate would have contact with nature and enjoy the fresh air, light and sun, hence the wide balconies and windows which opened out onto the landscape. This construction is considered historically as one of the first to humanise high-density housing.

Modernist perception

- Colour: one of Taut’s signatures is the use of colour. He is known as the chromatic architect of Modernism. Colour which supersedes the function is used to give the maximum vitality and liveliness to all external surfaces, achieving a dignified overall effect that seeks to identify the user with his space.

- Perception of type: In Hufeisensiedlung, the “perception of type” dominates over the racionalist or modern architect’s own “perception of the unique”. Taut applied the principals in this project that he would develop throughout his rationalist period in 1929:

- maximum utility

- constructive materials and systems completely subordinate to utility

- direct relationship between the building and its final use; leaving aside factors like symmetry or closed compositions, a better use of space can be achieved, and also improved economy in terms of distribution of resources. The spaces are distributed taking into account their projected function, without giving importance to a symmetrical configuration

- an aesthetic of the new architecture which does not acknowledge the separation between the façade and the floors, between the street and the terraces, between ahead and behind. The house and its details are not valued for themselves but form part of the whole. The concept of isolation and separation is discarded, living instead in relation to the buildings which surround us and converting them into a product derived from a collective and social disposition.

This project represented Taut’s idealisation of rural life in the suburbs of the city, combined with the sense of eclecticism which existed at the end of the 19th Century.

Construction

1925 – 1927

Between 1925 and 1925 the first phase was built, which was comprised of 1000 houses and became the first example of the construction of homes on a grand scale according to the principals of the New Construction and, for the first time in Europe, making worthwhile this type of project. This was helped by the size of the project, the use of excavators and cranes and the prior planning of a rational order for the activities.

1929 – 1923

Between 1929 and 1933 they added the single-family houses with terraces and gabled roofs which surrounded the main building and some apartment buildings for rent.

The houses were built following various standardised models but never in excessive numbers. The Horseshoe contained 150 identical homes, the “Fritz Reuter Allee”, 180.

The creation of the gardens and public open spaces was undertaken by the head of the department of the Parks and Gardens of Neukölln, Ottokar Wagler, who followed the original plans designed by esteemed landscape architect, Migge Leberecht.

Spaces

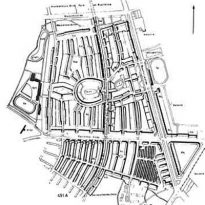

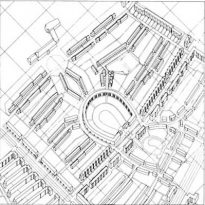

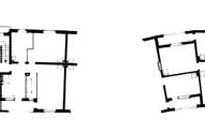

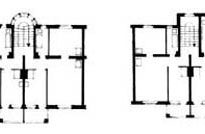

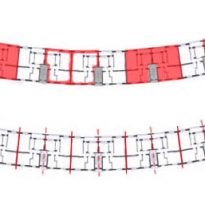

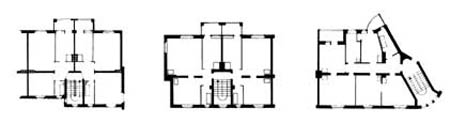

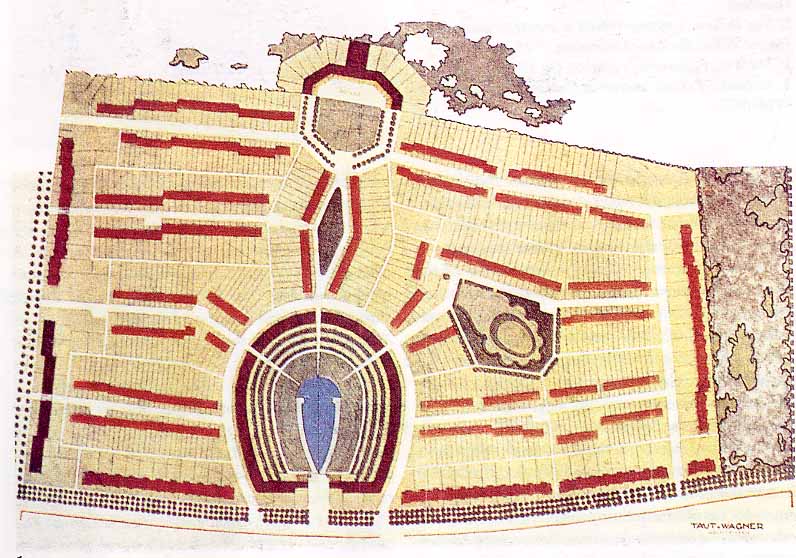

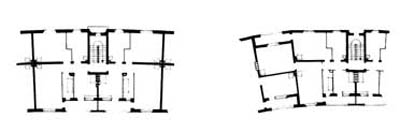

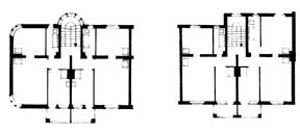

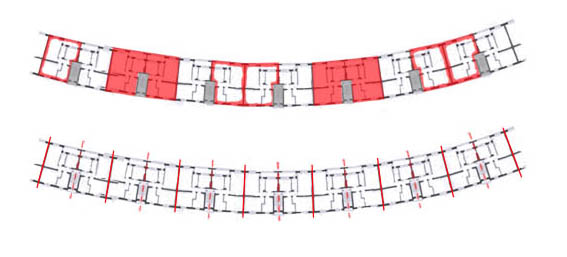

The residential estate formed seven blocks, built in seven phases from 1925 to 1933, in the modern architecture style, encompassing 1072 houses with four different layouts, of which 472 were single-family homes and 600 were distributed in three-floor apartment blocks. Unlike most typical social housing projects, like those previously built in Germany between 1920 and 1930, the slabs of these buildings were organised in blocks which defined the partial perimeter of the large interior gardens.

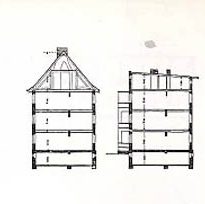

The various buildings varied in height and exterior details which achieved diversity without the typical format of a unified organisational structure. It is one of the first examples of a flat roof being used for a residential project in Berlin, which in 1920 was a controversial decision. Those in power were publicly against the idea, since they had always identified houses with gabled roofs, something that Taut though was a “romantic idea” with no real justification. However, some of the slabs had a stepped section which was made to overhang which tended to soften the hard profile of the flat-roofed buildings.

Some of the buildings were painted red, a further signal of the socialist inclination of GEHAG and their architect, while the colour blue for the balconies and part of the façade was highly criticised at the time but today has become symbolic of the zone.

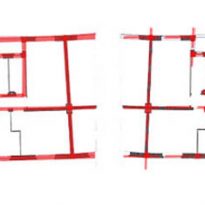

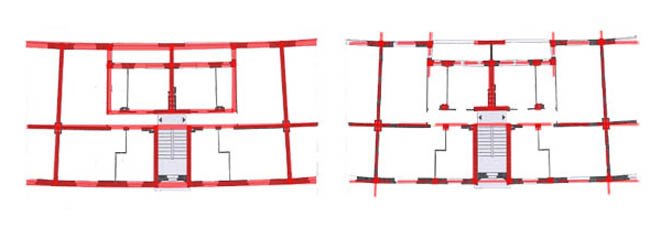

Central Building

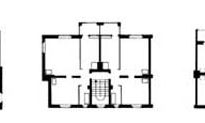

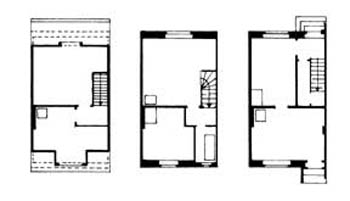

The main horseshoe-shaped building was built around an interior garden with a pond in its centre. This building followed a fairly conventional plan, with two or four bedroom apartments reached by a staircase. This staircase, on the façade next to the street, followed a repetitive pattern of glazed vertical sections alternated with regular windows.

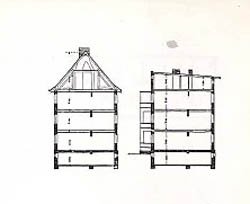

The balconies which open out on the opposite side dominate the façade facing into the garden. The small openings on the uppermost floor are characteristic of the residential buildings of this period, providing natural light to the communal attics, which were commonly used as laundries and storerooms.

In spite of some apartments being only 49m², they remain highly sought after as their rents have remained reasonable.

Single-family houses

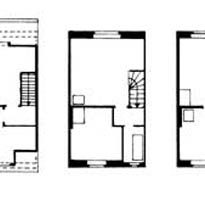

Around the main building, at a distance, they built rows of non-symmetrical houses, some with gabled roofs, others flat, with gardens and play areas, giving the place a villa-like aspect and combining the principles of the garden-city with the urban elements of a large block of houses.

The architect, Martin Wagner, head of urban planning for the city of Berlin during this period, had shown enthusiasm for the garden-city since the end of the war and accompanied Taut on his trip to England to design some of the slabs used in the construction. The two-storey houses, distributed in rows, included ample basements, gabled roofs and small skylight windows in the attics. The line of the buildings was adapted to the terrain.

Materials

In their construction, they used masonry materials, red bricks, gypsum plaster and some exterior ends in wood. The carpentry of the windows, divided in multiple panels, was also made in wood. Taut combined modern materials like steel and glass with the traditional materials of German construction, such as wood and masonry.

Another combining of modern with traditional architecture is seen in the flat roofs, which contrast with the traditional sloped roof covered in red tiles of some of the houses.

To improve and make more enjoyable the lives of the inhabitants of the estate, Taut combined a diverse range of colours for the façades; some houses were painted blue, others red.

The longest section of the façade of Fritz Reuter Allee is painted “Berlin Rot” (cherry red) for which its known as “Rote Front” (Red Front). The entrances to this building by this façade were painted bright blue.