The Museum of Islamic Art

Introduction

Islamic Arab societies have a distinctive, but culturally common system of beliefs, attitudes and values that over time have formed a traditional expression. These traditions have been articulated through art, architecture, community designs, social institutions and conventional behavior; all of which form spatial patterns. Knowledge about Islamic and Arabic architecture comes through numerous publications. Recently, in the Arab Gulf countries, the conservation of local identity has become the center of attention. Their attempts have been specifically demonstrated by the conversion of important historical buildings into museums, or the application of neo-vernacular architectural styles into newly constructed museums. One could question its specific use as museums. Museums symbolize cultural values, wealth, global status and a center of attraction. Although the building was designed by I.M Pei, a well-known architect outside the principles of Islamic design and local Qatari architecture, it is one of the most prominent monuments of the city and one of the emblematic icons of the neo-vernacular qatari. Architecture that catalyzes urban rejuvenation. (M Salim Ferwati, Qatar University)

Dedicated to reflect the vitality, complexity and diversity of the arts of the Islamic world, the Museum of Islamic Art collects, preserves, studies and exhibits masterpieces that span three continents from the seventh to the nineteenth centuries. The austerity of the exterior of the Museum contrasts with the use of decorative patterns and shapes used by Pei inside the building. Apart from the more elaborate metal canopy of the entrance, the building is essentially flat.

Location

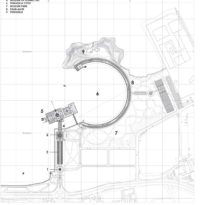

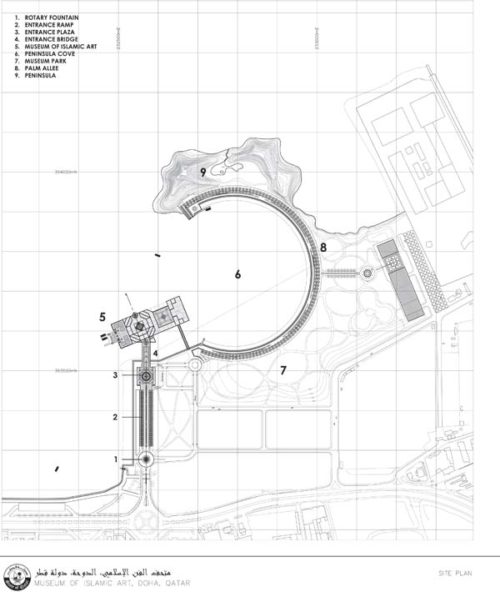

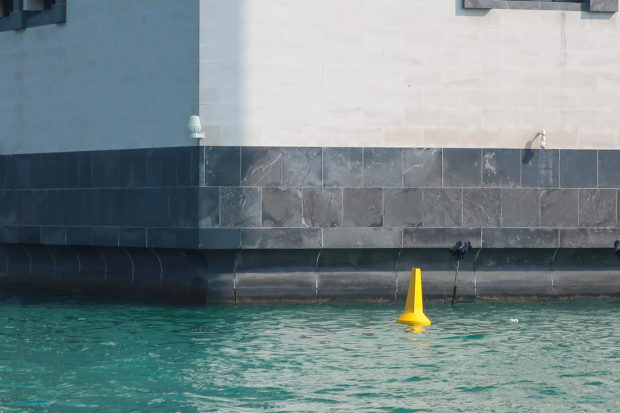

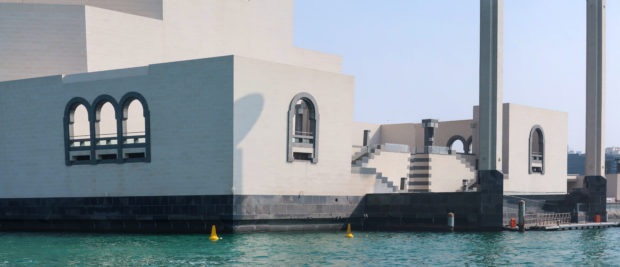

The Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar, was built on an artificial island located 60 meters from the coast, on the south side of the city’s Corniche, over the waters of the Arabian Gulf.

Pei refused to build the museum at any of the proposed sites on the Corniche, suggesting the creation of an independent artificial island somewhat away from the promenade, and thereby ensuring that future buildings never invade the museum. A park of approximately 64 acres of dunes and oases creates a new peninsula behind the Museum, offering refuge to the Persian Gulf from the north and to industrial buildings in the east, in addition to a picturesque backdrop.

Concept

Its faceted exterior planes and the breadth and layout of its interiors speak of a modern architecture but also of the essence of Islam. From the last century the culture is what has promoted innovation in this part of the Gulf, and with the fusion of the work of the architect IM Pei and the French designer architect Jean Michel Wilmotte, a bridge has been built that crosses the centuries, linking the culture Islam material with art and architecture.

The Museum of Islamic Art is the result of a voyage of discovery made by I.M. Pei, whose quest to understand the diversity of Islamic architecture took him on a world tour. During visits to the Great Mosque of Cordoba, Spain; to Fatehpur Sikri, a Mughal capital in India; to the Great Mosque of the Umayyads in Damascus, Syria and the ribat fortresses in Monastir and Sousse in Tunisia, he found that the influences of climate and culture led to many interpretations of Islamic architecture, but none evoked the true essence he sought. The inspiration for the final design was the 13th-century saber (source of ablutions) of the Ahmad Ibn Tulun Mosque in Cairo, Egypt (9th century). In the “… austerity and simplicity …” of the Sabil, Pei said, he found “… a severe architecture that comes alive in the sun, with its shadows and shades of color …”. The sable offered an almost cubist expression of geometric progression, evoking an abstract view of the key design elements of Islamic architecture.

The relationship between the final form of the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha and the high dome of the fountain of ablutions (sabil) erected in the central courtyard of the Ibn Tulun Mosque in the 13th century by Sultan Lajin Mamluk is clear, even through of the largest scale of the Pei building.

“… This severe architecture comes alive under the sun, with its shadows and shades of color. I finally found what I came to consider as the very essence of Islamic architecture in the middle of the mosque of Ibn Tulun… ”(I.M. Pei)

Spaces

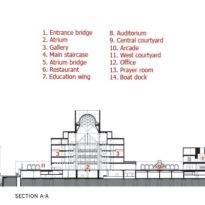

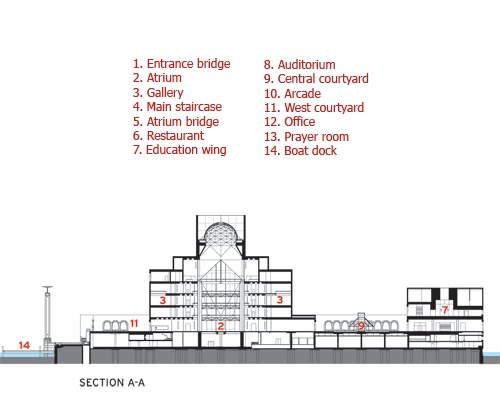

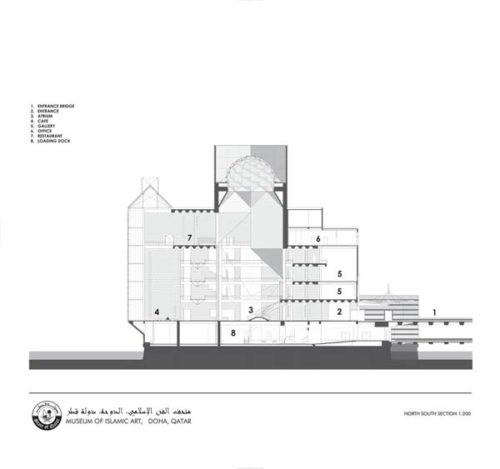

As one approaches the building, the entire weight of the structure begins to decrease, and the forms become more imposing. The bridge, flanked by rows of tall palm trees, is placed diagonally to the entrance, which makes the stacked geometric shapes appear more angular and the contrast between the light and the most extreme shadow. Soon some traditional details begin to appear: the two small arched windows above the entrance or the covered gallery that links the museum with an educational center. These touches seem minor, but they provide a sense of scale, so that the size of the building can be understood according to the size of the human body.

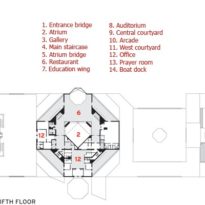

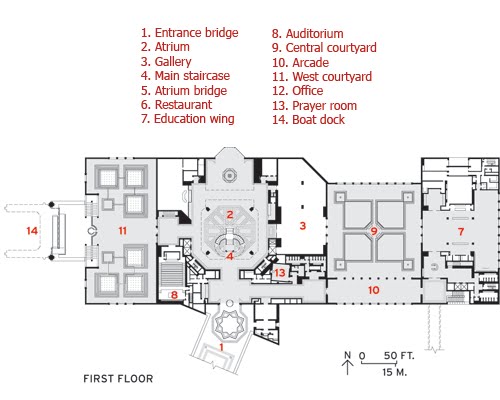

The museum, which consists of two buildings, the main one with 5 floors and 4,225 m² of exhibition space and the 2-story educational wing connected to the first one through a central courtyard, is connected to the coast by two pedestrian bridges and a vehicular bridge . Two 30.50m high lanterns mark the boat dock on the west side of the Museum, creating a large entrance for guests arriving by boat.

Inside, visitors enter one of the most sophisticated and advanced museums in the world, the result of the union of the French designer Wilmotte and the American Chinese architect Pei.

Main building

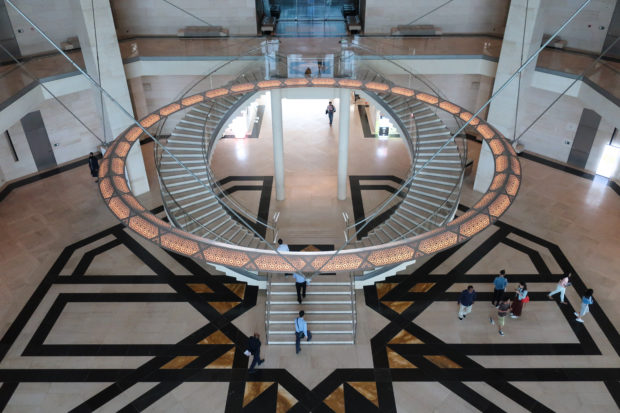

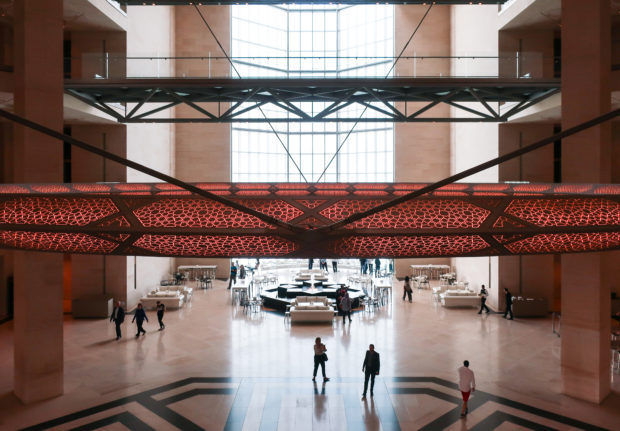

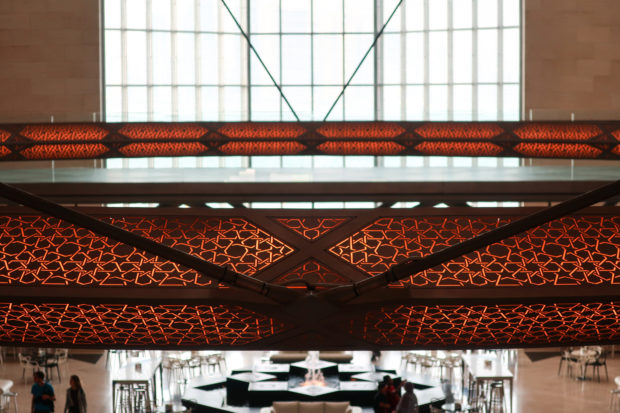

Atrium

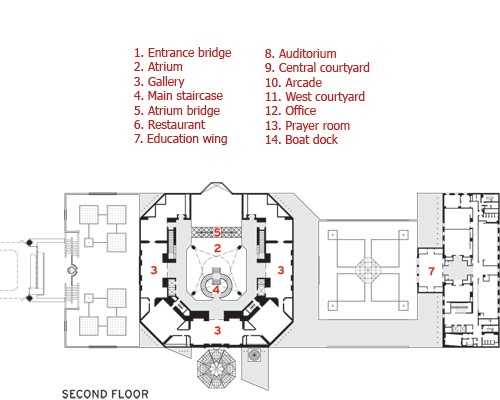

The angular volumes of the main building recede as they rise around a 50m high vaulted atrium, designed by Pei and hidden from the outside by the walls of a central tower. An ovule, at the top of the atrium, captures and reflects a pattern of molded light from within a faceted dome, allowing the rays of light to move along its surface, giving life and movement to the space below. On the beginning of the stairs, under the dome, hangs a spectacular and tubular circular chandelier with a diameter of 12m,

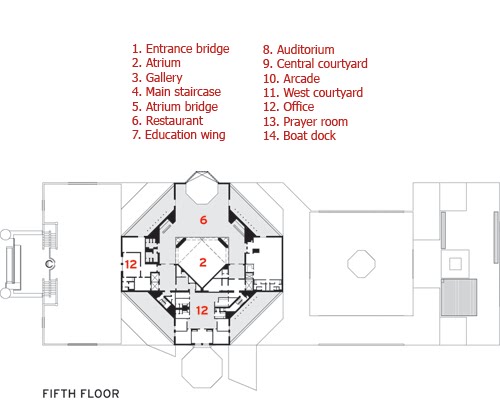

On the opposite side of the entrance, the north side of the museum, stands the only main window, a 45m high glass curtain wall that offers panoramic views of the Gulf and the West Bay area of Doha. This glazed wall can be seen through a sculptural double staircase specially designed to highlight the effect of light and the growing horizon of the new city towers. In this part of the atrium are the restaurant cafe tables, set by the sound of the water that flows from a particular octagonal black marble fountain.

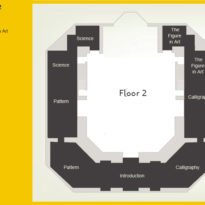

Galleries

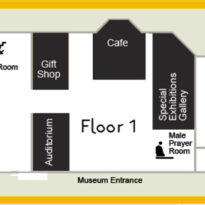

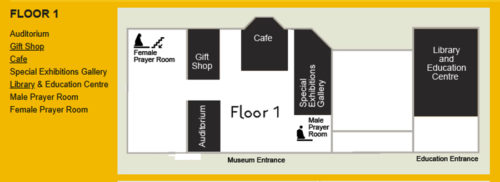

On the main floor 750m2 are distributed among the galleries of special exhibitions. Both these and the rest of the galleries were the work of designer Jean Michel Wilmotte, as well as the museum shop and offices, always within the forms created by the architect.

On this floor there is also an auditorium of 430m2 with 197 seats equipped with the latest audiovisual technology, a restaurant cafe and the prayer room for men, to the right of the entrance to the museum. The prayer room for women is located on the mezzanine floor, to the left of the atrium.

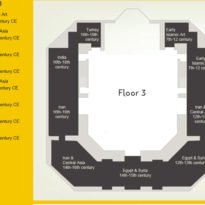

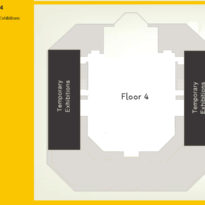

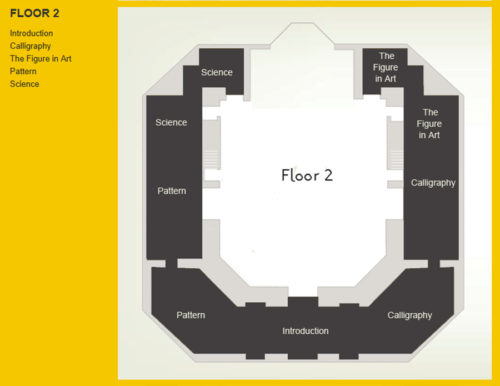

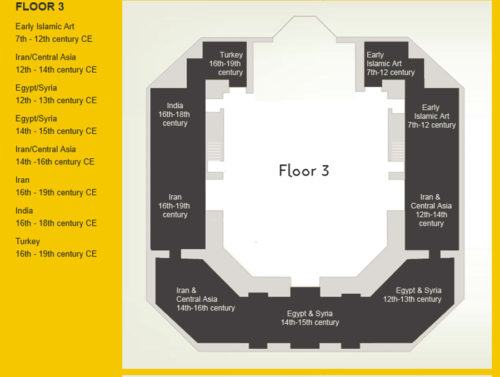

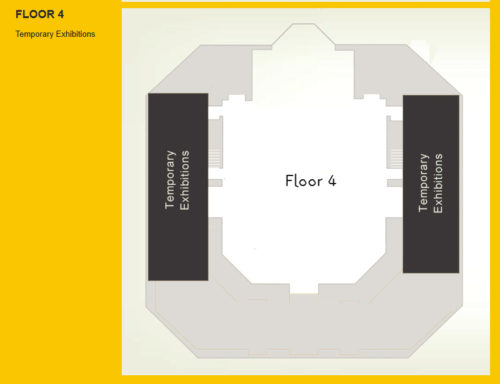

The galleries with permanent exhibitions are dedicated 3,100 m² distributed in two upper floors that surround the atrium and in the fourth the temporary exhibitions.

Pei provided the museum with a series of galleries with geometric arrangements that were essentially “black boxes” and put in the hands of the French designer Wilmotte to turn them into vibrant spaces where to exhibit Islamic decorative arts. The designer played with a subtle range of high quality dark materials that highlight the exposed piece making it the protagonist, despite the huge glass doors in the showcases, operated only by a button, or the dark-carved gray stones that line the walls , all wrapped by a suggestive and intimate light.

The galleries are literally made to allow visitors to appreciate objects of utilitarian origin. The cabinets created by Wilmotte fade and float in the air to improve the works. Wilmotte & Associés managed not only to give visibility to these objects, but also, by mutual agreement with the local administration and I. M. Pei, to impart all the majesty they deserve as works of art. The solidity and subtlety of the accessories are manifested in what Pei sought and what he calls “the essence of Islamic architecture.”

Circulation

Each level of exposure is crossed by bridges with glass floor that pass over the cafeteria of the fountain, completing the circulation route of the U-shaped balconies cantilever around the atrium. The transparency and height of the bridges that cross the atrium gives them a vertiginous appearance.

Educational Wing

The educational programs of the Museum are located in a wing to the east of the main building that is joined by a courtyard with fountains. The education wing, with 2,694m2, includes a brightly lit reading room in the museum’s library, classrooms, workshops, study spaces and technical and storage facilities.

Dimensions

The building has 35,500m2 distributed as follows:

- 4.225m2 exhibition space

- 3,100m2 for permanent exhibitions

- 750m2 for temporary exhibitions

- 375m2 for study galleries

- ceremonial entrance and 280m bridge,

2.700m2 educational wing:

- 820m2 library

- 400m2 conservation laboratory

- 1.800m2 warehouse, 430m2 auditorium

- 380m2 bar-restaurant

- gift shop 300m2

Heights

- Highest point inside 50m

- outside 63m

- 45m glazed north facade

- luminous pillars at the pier 30m.

Others

- 12m diameter lamp of lights in the main atrium.

- Park surrounding the museum, including the peninsula, 26 hectares.

Structure

With steps on both sides, the apex of the main building is dotted with a short tower with an eye-shaped opening that masks an inner dome. From certain angles, the structure has a flat and chimeric quality, as a scenario, from others, seems to be floating on the surface of the water.

Dome

A geometric matrix transforms the descent of the dome from a circle to an octagon, to a square and finally to four triangular fins, which lean at different heights to become the columns of the atrium.

The structural system that supports the dome is not particularly elegant, on the one hand, the drum that supports it rests on thin columns three stories high, on the other hand, extends down to meet a wall that encloses an office floor before leaning on a series of shorter columns, altering the natural symmetry of the room, although the meaning of the space is clear.

Although the central dome of the Museum can remember a certain number of mosque structures, the architect has not aligned his building or his large window in the direction of Mecca. The “mihrab”, a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the “quibla” (direction that Muslims must face when they pray), is rarely designed as a window, although the elongated and axial shape of the large window The museum recalls this aspect of Islamic architecture. However, the prayer facilities inside the Museum naturally take the correct alignment and turn slightly with respect to the rest of the building. These are the moments in which Pei’s architecture must be incorporated, the architect placed culture as religion on the same pedestal. His museum reminds us that building a culture, as much as a political or social agenda, can be a healing act. Like all great art, it requires forging seemingly conflicting values into a common whole

Substructure

The construction of the substructure for the Islamic Art Museum building, a structure completely surrounded by water, involved the creation of a structural filling platform contained within a specially designed “driven” concrete pile enclosure. Appropriate temporary works and dehydration schemes were implemented.

Work also included the construction of piles, large pile caps, grade beams, “pressure” grade slabs and deep wells. The scope of the works also included the formation of a new cove and peninsula to remodel the existing coastline, which included 2.5 km of prefabricated and rock cladding works. In its construction, 200,000m3 of structural fill and 30,000m3 of concrete were used.

Materials

The building was constructed with noble materials, such as cream-colored limestone Magny and Chamesson from France covering the exterior facades, the Jet Mist granite from the United States and stainless steel from Germany, as well as the architectural concrete from Qatar.

The structural framework of the dome that illuminates the central space of the atrium was made of stainless steel. The ceilings are constructed with intricate pieces of architectural concrete in the form of small domes embedded in the place and finished with individual molds.

The large glazed wall facing the Gulf is protected from the sun and outside noises by means of a damping screen made of aluminum acoustic bars.

The galleries feature dark gray porphyry stone and Louro Faya, a Brazilian lace wood that was brushed and treated to create a metallic appearance, which contrasts with the light-colored stone from the rest of the Museum. To protect the fragile antiques on display, the rooms have specially designed cases and lighting. Wilmotte also created custom furniture for the museum, inspired by Pei’s architectural style.

Videos