L’Esprit Nouveau Pavilion

Introduction

The Pavillion de L’Esprit Nouveau was a temporary building created in 1925 within the framework of the International Exposition of Decorative Arts in Paris. Le Corbusier took the chance to provocatively display his ideas about architecture and urbanism, which he had started to develop along Pierre Jeanneret since 1922.

Such ideas were rare at a time where the Art Nouveau was considered primarily a decorative art; the response against this project was frankly hostile.

The exposition organisers’ attitude stems from the participant’s reject of decorative art. A four-meter high fence was built around the pavilion to hide it from the public eye, later removed thanks to the intervention of the Minister of Beaux-Arts during the exposition’s inauguration.

Location

The Exhibition took place in the centre of Paris, France, tracing both skirts of the river Seine and finally surrounding the Gran Palaix. Every exhibitor was granted a space big enough to host their pavilions and respective gardens.

Concept

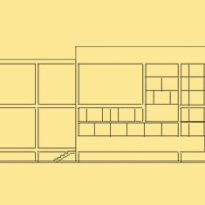

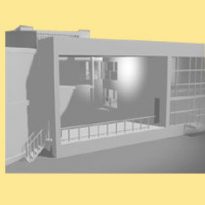

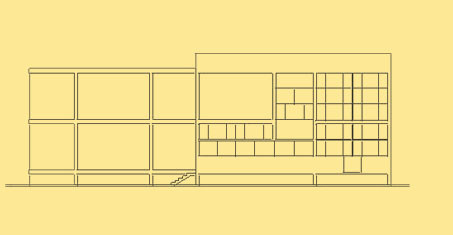

The pavilion’s new conception of “habitable space” discards all decorative notions. Le Corbusier attempts to demonstrate that architecture is overall present, be it in the most humble domestic equipment or in a manor, a district, a city, etc. It is a question of proving that reinforced concrete and steel (at a time in which these materials were regarded as undignified by architectonical masters) offer many architectonical possibilities, particularly for series housing, and demonstrating that industrialisation through standardised materials and art are not mutually exclusive.

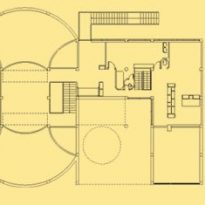

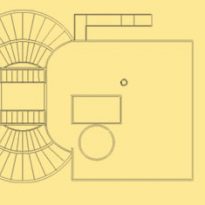

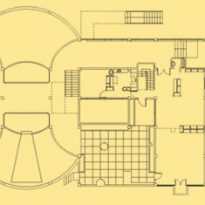

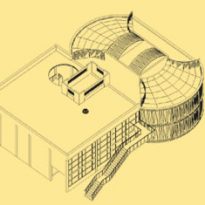

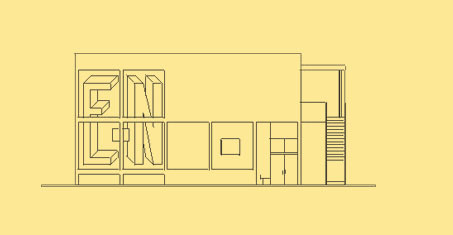

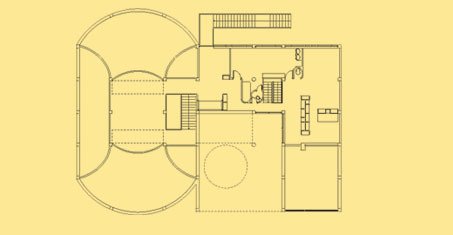

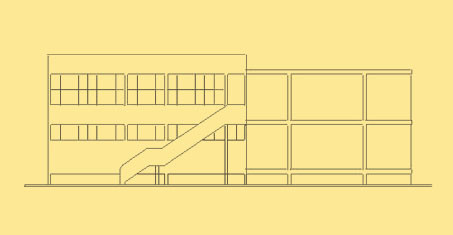

Next to the pavilion, a roundabout, reachable to the public, was established for the presentation of great urban projects. Two dioramas exhibited, in approximately 100 square meters, the Contemporary Villa with 3 million inhabitants (1922) and the Plan Voissin (which owes its name to the sponsoring industrial), which suggested the building of a business city in the urban centre of Paris. These scenes were accompanied by revolutionary urban and architectonical plans: a real vision of tomorrow’s world. The Pavilion of L’Esprit Nouveau was, in fact, a natural scale model from one of the aforementioned cells.

The Villa’s prototype constituted one of the Modern Movement’s models due to the emblematic, radical synthesis of its proposal. The familiar unit was hosted in purist quarters, with refined designs and resolutely constructed, which continued on to private gardens allocated across space.

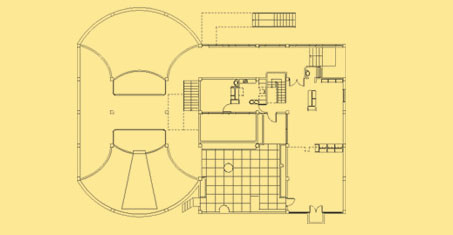

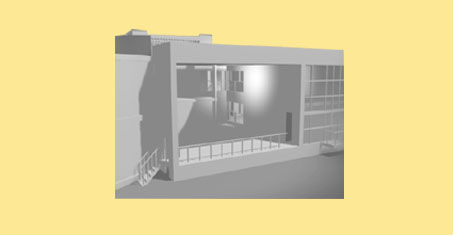

On a side note, in the Pavilion’s chosen location grew a tree which could not be brought down. Le Corbusier’s solution was to adapt his architecture around the territory’s requirements.

The Pavilion de L’Esprit Nouveau marks a milestone in architectonical evolution. The concept of furnishing is replaced by that of equipment, which affects the distribution of different essential elements for the habitat’s daily functioning as a consequence of its utility. Standardised, industrial furniture replace the inner walls and distribute the different functions. Each responds to and is defined by its purpose: library, clothes, dishes, etc. The designer Charlotte Perriand collaborated at the stage of equipment design.

Spaces

This living unit constitutes an ingenious way of synthesising elements such as privacy and the intimacy of an individual’s space with the socioeconomic imperative of collective housing.

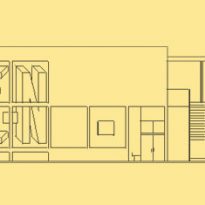

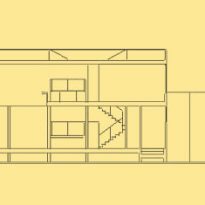

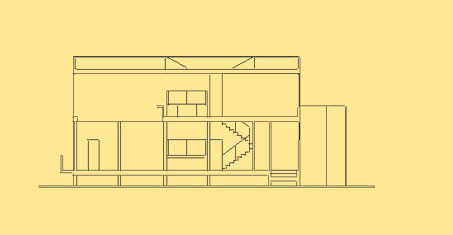

Essentially, the unit is based on the Maison Citröhan style, with the reception and kitchen on the first floor and quarters on the second floor, acting as balconies over the living space. However it was developed around a garden-foyer which stood at double height, serving as a “lung” of space for the unit, making it possible to transmit different atmospheres.

This foyer, fully integrated in the central cell, serves as a “toiture-garden”, one of the well-known five points stemmed from the first Citröhan prototype (1920). The Citröhan’s terrace, designed to host individual households, could not endure serial housing; but by locating the foyer adjacently to the unit, the unit becomes apt for juxtaposition and stacking next to others in a collective multi-person building. As such, it will reappear in different projects through the period, demonstrating a notable versatility – even in peculiar, atypical cases such as the Argel Plan.