Glessner House

Introduction

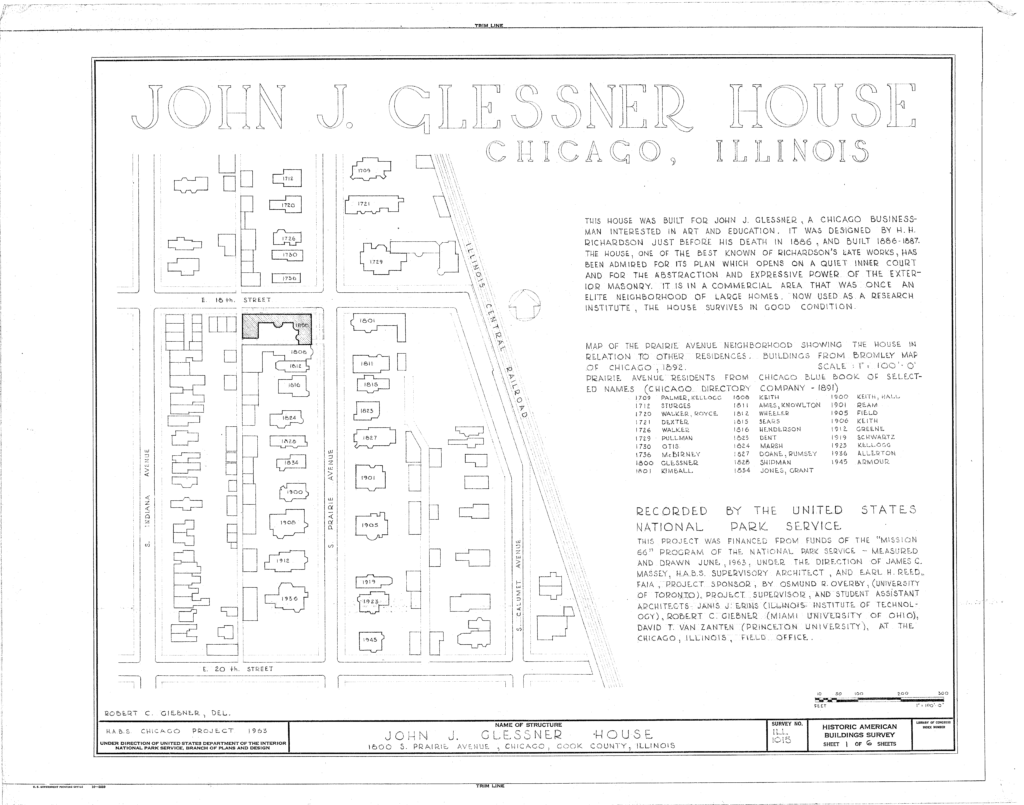

In the summer of 1885, H.H. Richardson sat not only at the pinnacle of his career, but also at the top of the list of American architects. On May 2, 1885, Chicago’s Real Estate and Building Journal announced that John J. Glessner, a Chicago partner in a large farm equipment company that would eventually be merged in 1902 to create International Harvester, had asked Richardson to design a house at the corner of Prairie Avenue, the most prestigious residential street in the city, and 18th Street. In order to understand his design, one must be familiar with the state of Chicago’s political climate between its business leaders and the working-class poor at the time. Following the economic crash of 1873, Chicago had been a hotbed of union activity fighting for the 8-hour workday.

In October 1884, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions had held its annual convention in Chicago where it set a deadline of May 1, 1886, for a nationwide walkout to force the issue. On the following Thanksgiving, the local branch of the International Working People’s Association had sponsored a “Poor People’s March” in which the protestors had purposely walked past the homes of the rich, stopping in front of the homes of the wealthier industrialists to hurl verbal epitaphs at those celebrating behind their bolted doors. On April 28, 1885, a grand banquet was held in the city’s new Board of Trade, scheduled to open two days later. The IWPA held another parade to protest the new building that had been redirected by restrained police action only a few blocks from the gala. Richardson had first met with the Glessners only a few weeks after this latest incident.

Unfortunately, Richardson would not live to see the house completed as the 47- year old finally succumbed to his chronic bout with Bright’s disease on April 27, 1886. Two days before, on Easter Sunday, April 25, 1886, only six days before the scheduled start of the nation-wide walkout, buildings on the West side of Chicago were bedecked with red banners, for the Central Labor Union had organized a march to shore up support that day reported to have involved over 15,000 people. On Saturday, May 1, D-Day, it was reported that between 40,000 and 60,000 had walked off their job in Chicago that morning, while over 80,000 later in the day marched down Michigan Avenue in support of the national General Strike. That night and the following Sunday, the beerhalls and bars in Chicago, the center of the storm, were alive with talk of this success and what was to come next. Meanwhile, Chicago’s business leaders were readying their own plans: for the city’s elite had convinced the city’s leaders to station a force of 200 policemen to put a stop to any attempt to convince their non-union workers to stop work and join the walkout. The police wasted no time in dispersing a mob of strikers with clubs and pistols the next day, Monday, the first full-day test of the eight-hour day.

The movement’s leaders called a protest meeting for the following evening, Tuesday. May 4, 1886, a day that still lives in history. During the meeting, a bomb was thrown into a group of policemen igniting what is called, depending upon your political leanings, the Haymarket Square affair, riot, or bombing. The final recorded death toll included eight policemen, at least four bystanders, and five of the eight leaders of the movement who were rounded up in the ensuing dragnet and found guilty of murder (one committed suicide in jail while the other four were hanged). The final fatality was the eight-hour movement (at least for the next two decades). Two weeks later, the Glessners signed the construction contract for their new house.

Location

Chicago: the southwest corner of S.Prairie Avenue and E.18th Street.

Concept

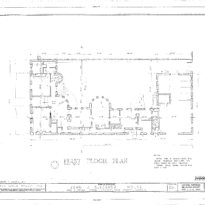

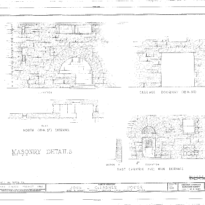

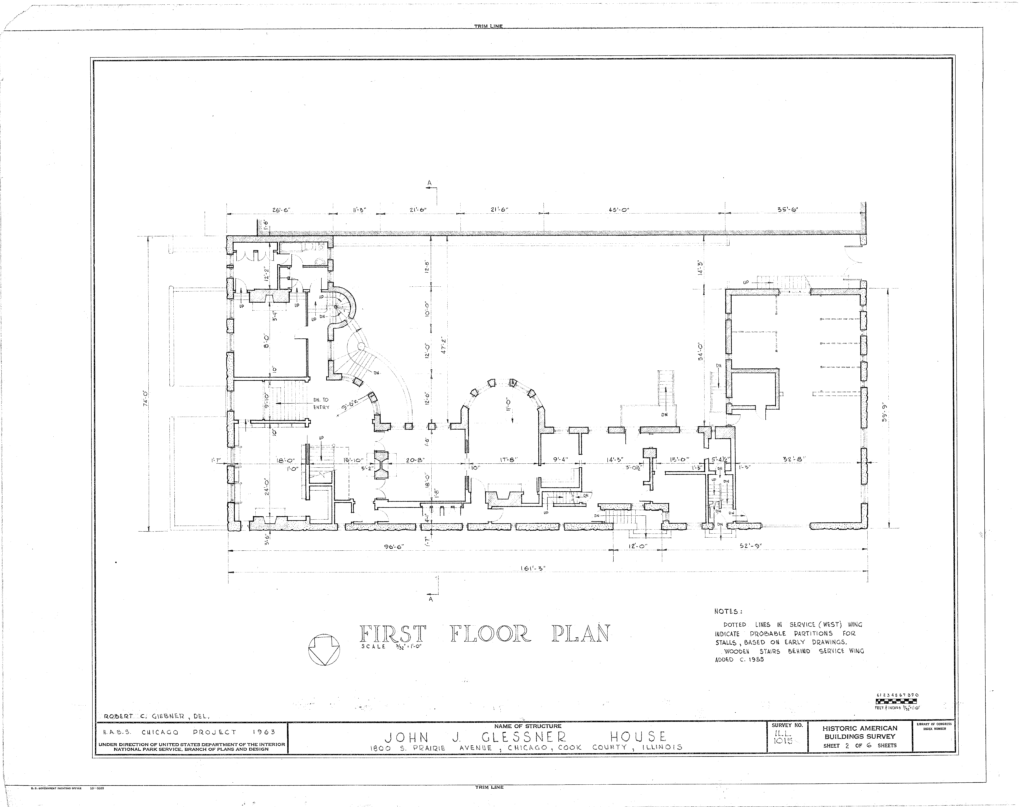

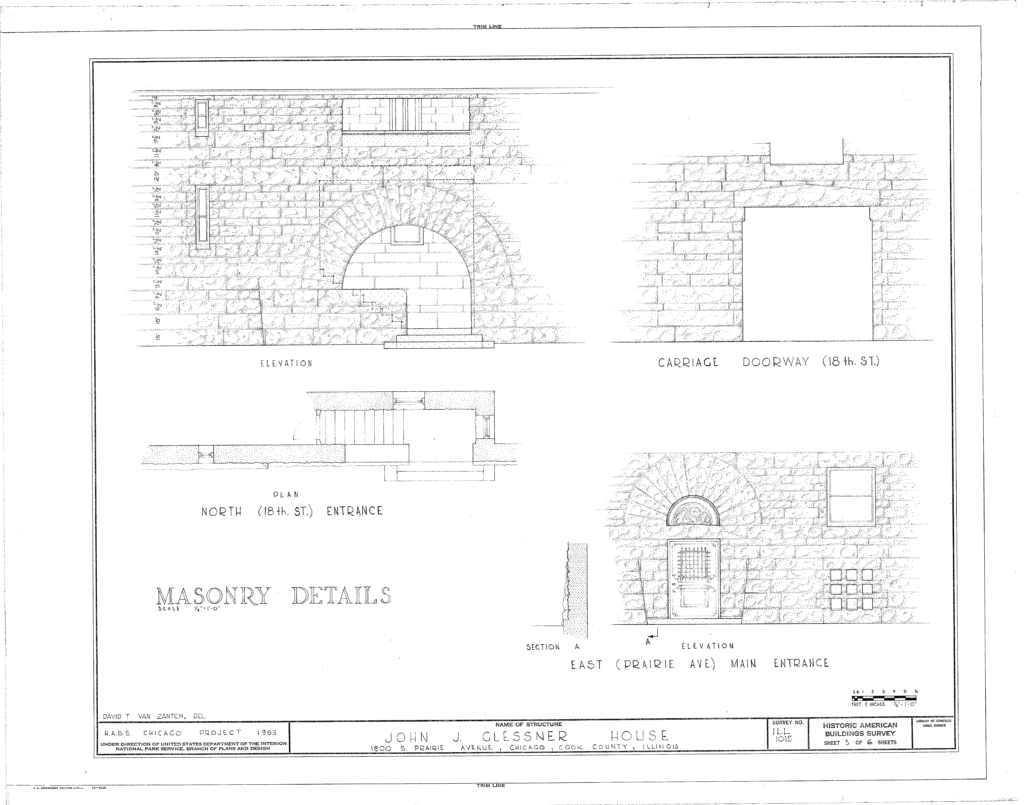

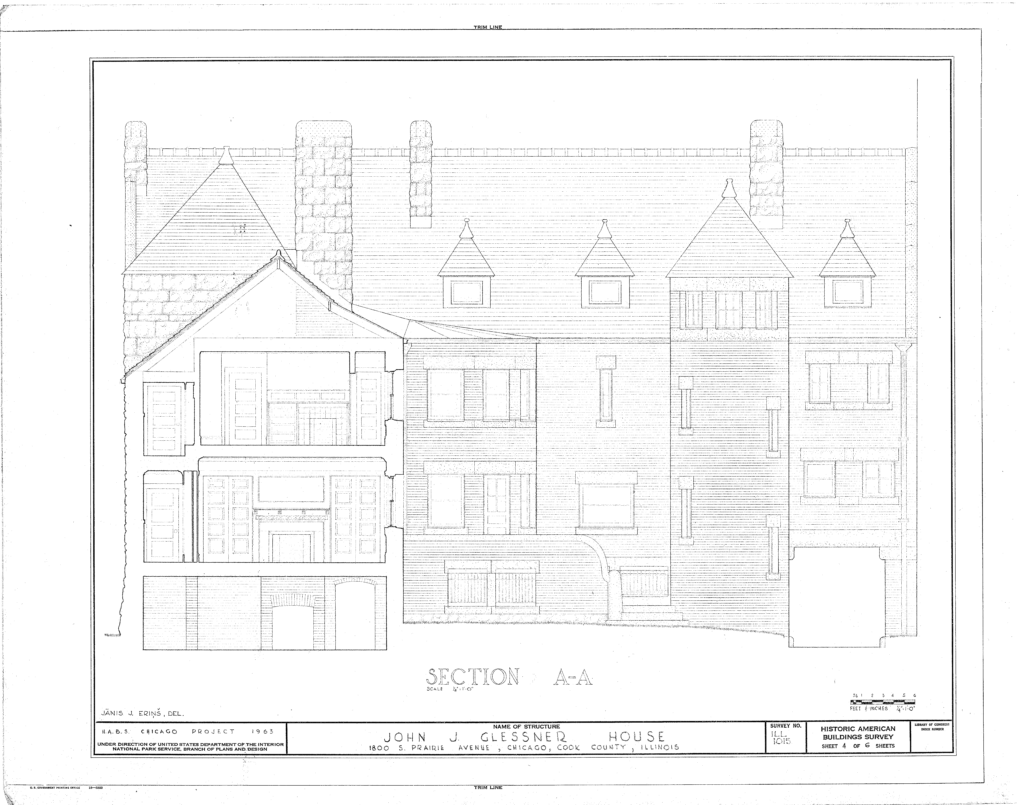

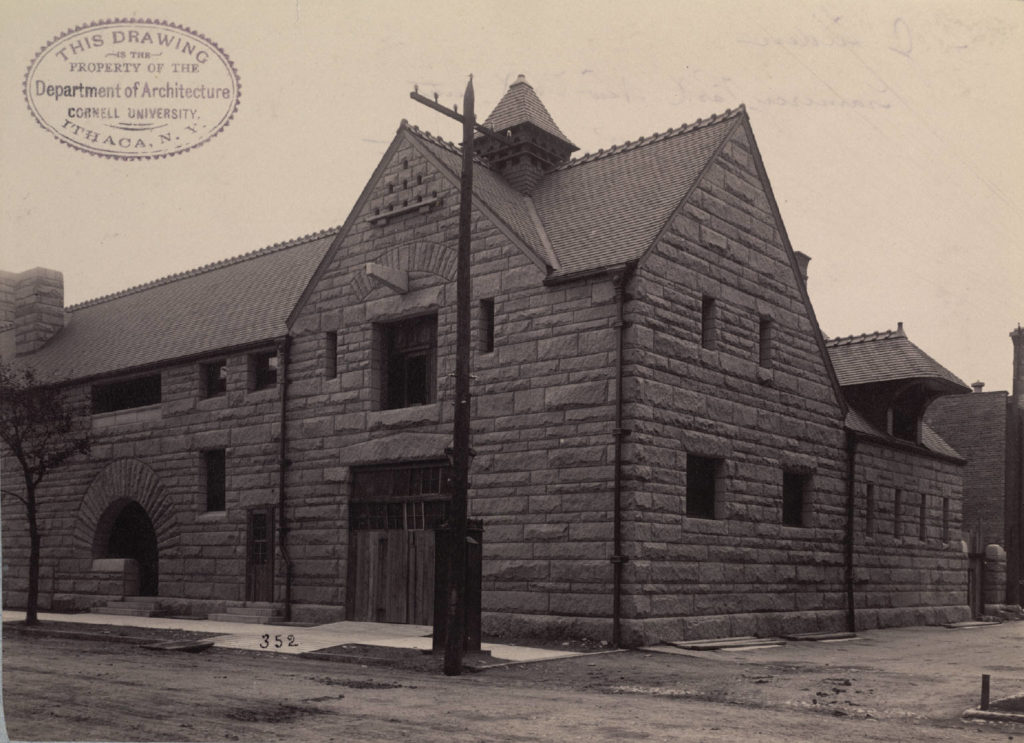

Richardson had produced an entirely new approach to a Chicago house. Instead of the setback, freestanding suburban box in a field of green grass, he had designed an urban Florentine Renaissance palazzo, pushed right up to the sidewalk. Judging by the fortress-like image it presents to the street, protecting his family from the street mob and concerns over having his children kidnapped were, indeed a major concern for Glessner. Note there are no windows on the ground level, and other than the four on the main floor overlooking Prairie Avenue, there are only a number of tall, but thin rectangular windows along the longer 18th St elevation, intended to provide light for the servant’s corridor located against this wall, that in a moment’s notice could just as easily be used as rifle slits. The house has only two entrances with an opening immediate above each that, if need be, could be used for defensive purposes. Most interesting, he downplayed the front door while he celebrated the service entry on 18th St. with his characteristic overscaled arch with cyclopean voussoirs. It was almost as if he and the Glessners wanted to trick any would-be attackers to focus on the service door and away from the front door.

To complete the fortress or castle analogy, visitors arriving in a carriage would have to first pass through an entrance tunnel, located to the left of the main entry, protected by two heavy gates or portcullises. The first gate facing the entry would be opened, allowing the carriage to enter the tunnel while the second gate remained closed to ensure no unwanted visitors could rush into the interior courtyard. Once the first gate was secured, the second gate was opened and the carriage could continue into the courtyard where its passengers could then exit and be greeted. The carriage would then either continue straight to an exit gate or turn left into the adjacent stable.

Materials

The exterior is faced with Braggville (MA) granite. But if one saw only the courtyard elevations of the house, you would never associate them as having been from the stone fortress that shows on the exterior, for Richardson faced these with a residential-scaled Chicago common brick.

Spaces

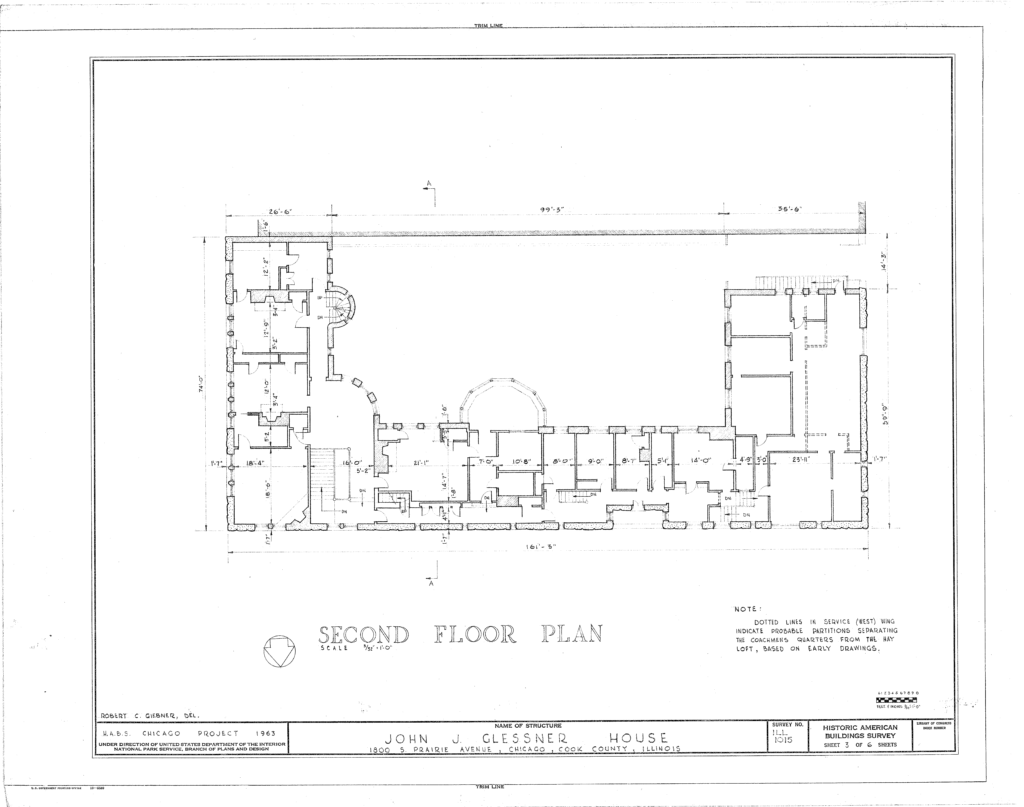

During his European trip in 1882, Richardson had the good fortune to run into William Morris while in London and the two of them spent a few days together discussing their professional interests. The Glessners were also followers of the Arts & Craft movement, having a few Morris pieces in their old house. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that in the plan of the Glessner House, one could argue that Richardson had been influenced by Morris’ Red House. We have the same Pugin-inspired L-plan and the front entry and circulation systems are quite similar to the Red House, with the exception that Richardson has moved the stairway and servant corridor to the back, or north wall, which had the added advantage of insulating the hall, dining room, and parlor from the winter north winds.

Fortunately, the site that Glessner had purchased was located on the south side of 18th Street, facing north. It was so oriented that Richardson could line the two street fronts with solid walls that would also protect the interior from the winter winds off Lake Michigan. The amount of glass used in the courtyard elevations allowed views from the interior to the courtyard, and daylight to enter into the interior spaces that opened to the south to allow the sun to light (and passively heat during the winter) the interior of the house and its exterior yard. In conjunction with the adjacent house’s southern wall and the Glessner’s attached coach house, the courtyard was completely enclosed. In the self-contained courtyard: he had given the Glessners a model of urban domesticity. Richardson had completely inverted the residential model of Chicago; instead of putting the house in the middle of a grassed lot, he has put the grassed lot inside of the house. It was as if the Glessners had turned their backs to the rabble of the street and created their own private Garden of Eden.

Structure

Exterior brick bearing walls with stone veneer. The interior structure consisted of timber beams and flooring.