Bauhaus building in Dessau

Introduction

Bauhaus, etymologically meaning ‘House of Construction’, was founded in 1919 in Weimar (Germany) by Walter Gropius, moved to Dessau in 1925, and disbanded in 1933 in Berlin. The spirit and teachings of the institution can be said to have extended throughout the world.

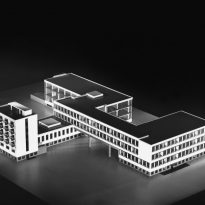

With the move from Weimar to Dessau, the Bauhaus had the opportunity to create a building which would provide the optimal working conditions to develop its own design, which was taken forward by their very own Walter Gropius and inaugurated on the 4th of December 1926, rapidly becoming an icon of the beginnings of the Modernism movement.

…”Architects, sculptors, painters, we all must return to manual labour!… Let us establish, therefore, a new confederate of artisans, free from that arrogance which divides one class from another and which seeks to erect an insurmountable barrier between the craftspeople and the artists! We long for, we develop and together we construct the new building of the future, which will accommodate everything- architecture, sculpture and painting- in one entity and which will rise to the sky by the hands of a million artisans, a crystal clear symbol of a new faith which has arrived…”- Walter Gropius.

With the Bauhaus building, Gropius put in practice his ambition to design processes of living, in order to unite art, technology and aesthetics in the search for functionality. It was born from the merging of the Academy of Fine Arts and the School of Arts and Crafts, in an attempt to overcome the existing divorce between art and industrial production on one hand, and art and crafts on the other. The use of new materials and technologies was promoted, without devaluing the artisan legacy.

Location

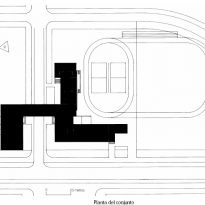

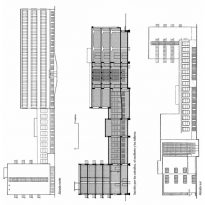

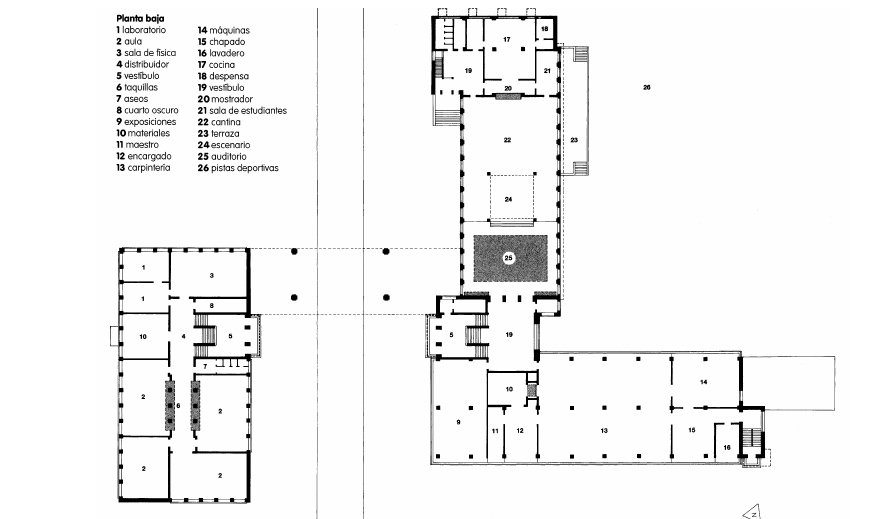

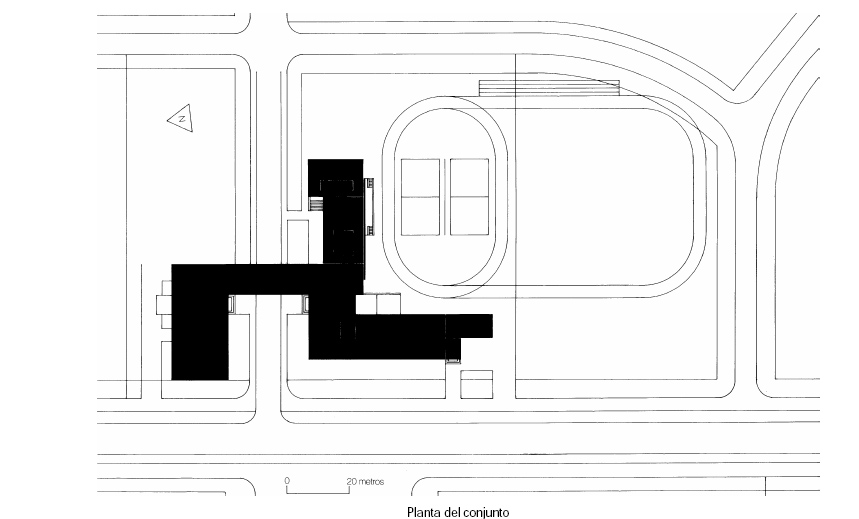

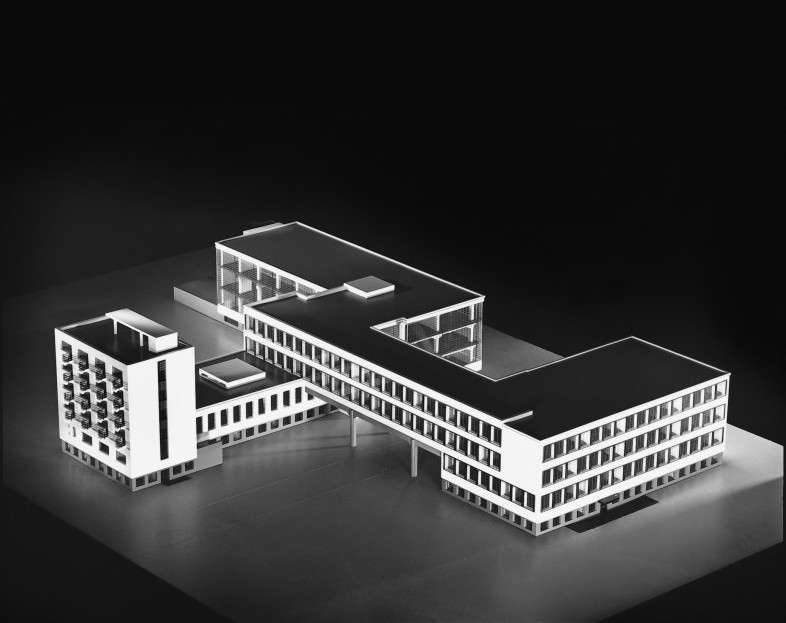

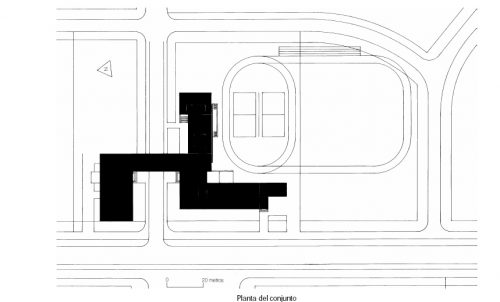

The building seems to draw the reasons for its configuration from the circumstances in which it is found: confined by a street, with another crossing perpendicular to the first and with two of its wings bordering a nearby sports ground.

Its postal address is: Gropiusallee 38, 06846, Dessau, Germany.

Concept

After the First World War, the defeated Germany sought an escape from the crisis of values in which it found itself immersed. Its intellectuals believed that the political irrationalism had led to the violence, and a critical rationalism had to be imposed in order to resolve the social conflict.

Gropius felt himself to be strongly involved with these concepts. His great manifesto for architectural rationalism would be the exceptional Bauhaus building, in which they would bring together the characteristics of the Modernism movement: rationally articulated pure spaces (functionalism); innovative usage of new materials, such as the glass curtain-walls in the façades; horizontal windows; an absence of ornamentation; a global design for all elements; and, above all, a spatial conception presided over by the interrelation between the interior and exterior by means of the glass wall.

These principals gained rapid approval and were consolidated internationally in the housing projects of Mies Van der Rohe, the previous director of Bauhaus, at the Weissenhof Urbanisation built near Stuttgart.

Description

Facades

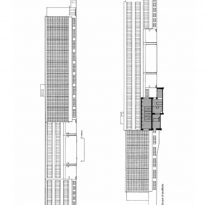

More than anything, the façades testify that the Bauhaus is very much a typical building of modernity. Although you can search, you will never find the main façade. All were made with an “affection” for the details, all with the intention that the function be easily recognised from the outside.

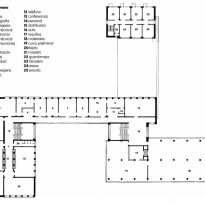

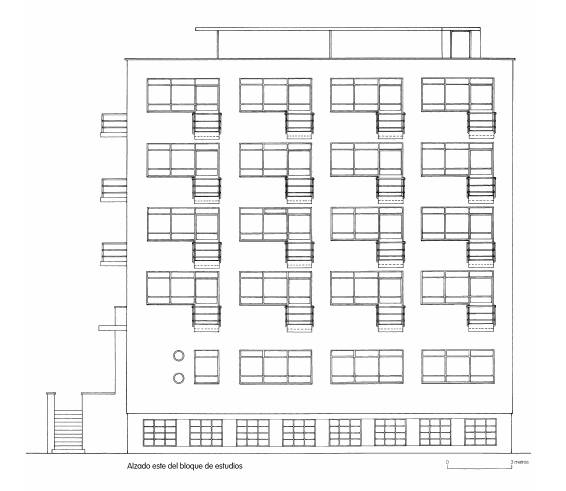

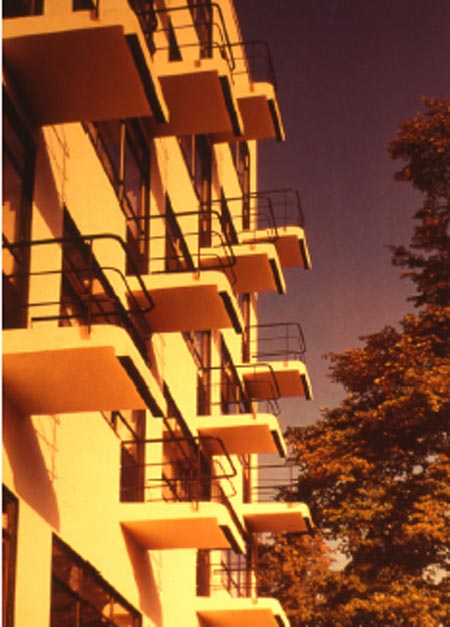

Each façade corresponds to the requirements of the activity which takes place inside: the façade of the block of classrooms is formed of horizontal windows, whose function is to ensure adequate light; while the apartment building, on the contrary, has small individual apertures designed to increase privacy.

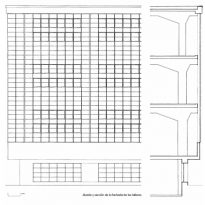

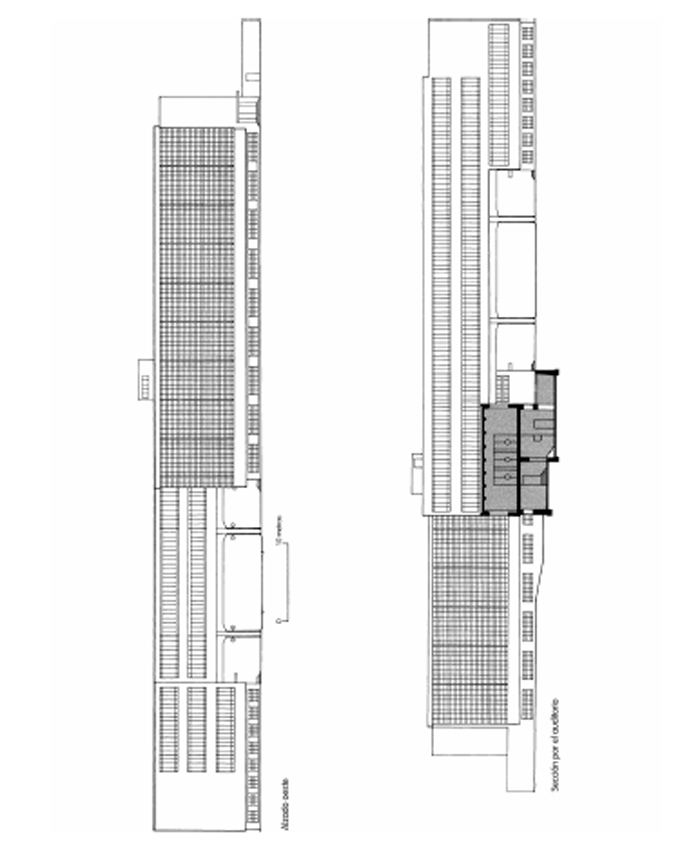

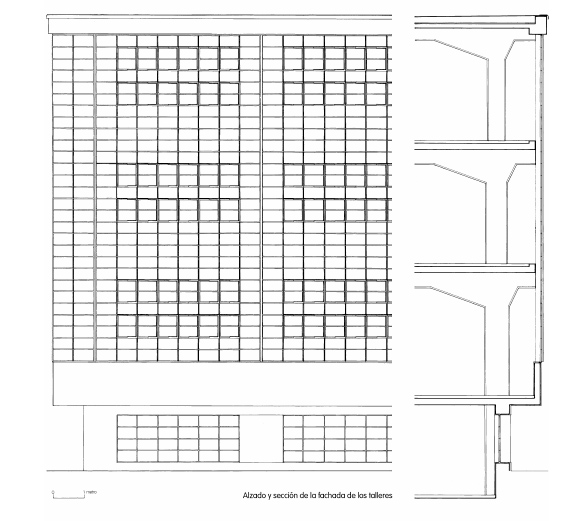

The workshops display an imposing glass frontage, which permits the maximum illumination and view of the interior from outside. In this façade, Gropius revisited the theme of Faguswerk and the Cologne factory, establishing a glass closure which sits over the front of the structure, keeping the pillars tucked in and adding a cantilever which allows the corner buttress to be eliminated, thus creating the famous image of angular transparency which constitutes one of the most typical formal aspects of the Bauhaus.

The front façade is where the first level is set back, to produce the levitation of the upper volume comprised of a curtain wall, which creates a tension toward the access, as a result of the contrast of opacity with the lower volume.

Roofs

Flat roofs of vast extension were designed. However, there was very little experience with similar constructions at that time. As such, the construction of the roofs encountered various problems. The biggest of these was the inclination of only one degree. The next was the interior drainage, and lastly they did not use gravel drainage, so that the sun radiated directly onto the layers of tar, deforming the layers as there were no expansion joints. As a result, the roofs of the Bauhaus were never waterproof.

Spaces

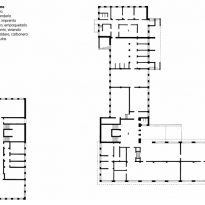

The main entrance of the Bauhaus is divided by three doors, separated by red columns, which provide access to the entrance vestibule and stairs.

Staircase

The stairs were designed in three parts: the part in the middle is the widest and leads to the upper floors, the narrower laterals descend the levels. In front of the staircase, there is a large floor-to-ceiling window which is as wide as the stairs.

Vestibule

Going up half a level, you arrive in the lobby; a very interesting space for its component elements.

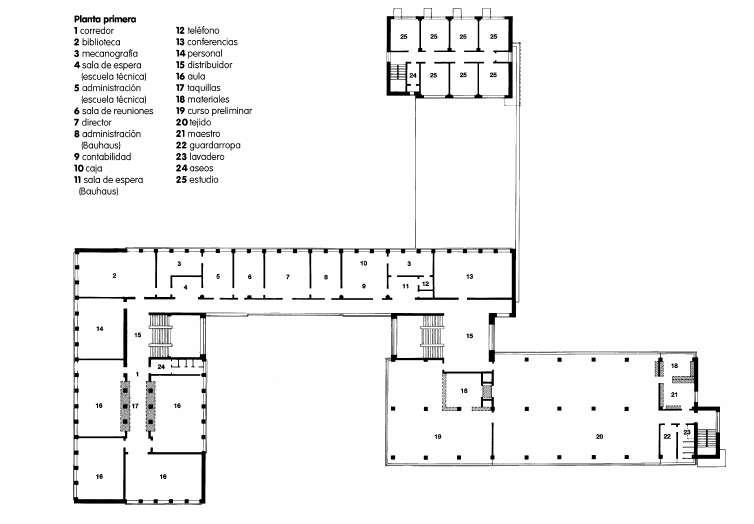

A very characteristic feature of the Bauhaus building is that in walking the corridors or stairs, there are almost always various possibilities for where to go, as a result of which the different sections of the building achieve a certain correspondence.

Ascending the stairs from the lobby, you cannot only reach the workshops and administration, but as there are large windows located at either side of the stairs, on each step you can see a new perspective of the interior, but above all, the exterior.

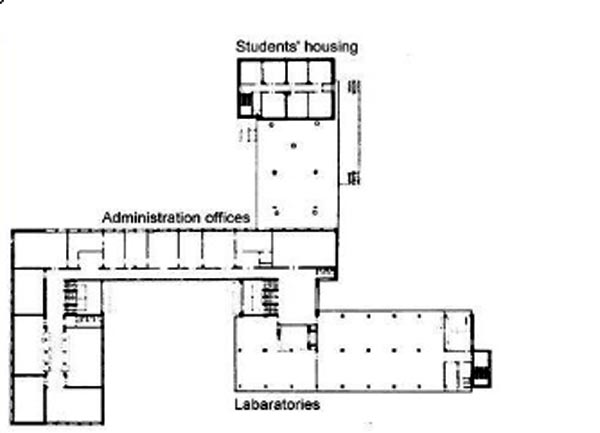

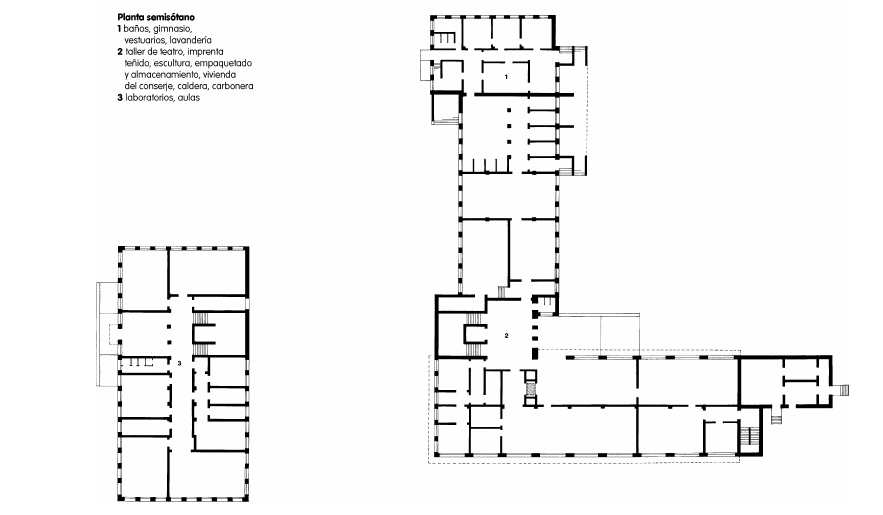

The building is distributed over three main wings, interconnected by a bridge element, whose X-shaped form breaks with the concept of symmetry and gives its functional efficacy precedent over its aesthetic coherence. It was characterised by orthogonal levels and sections, generally asymmetric, and an absence of decoration on the façades. The interior spaces are bright and airy.

Technical education

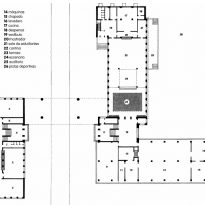

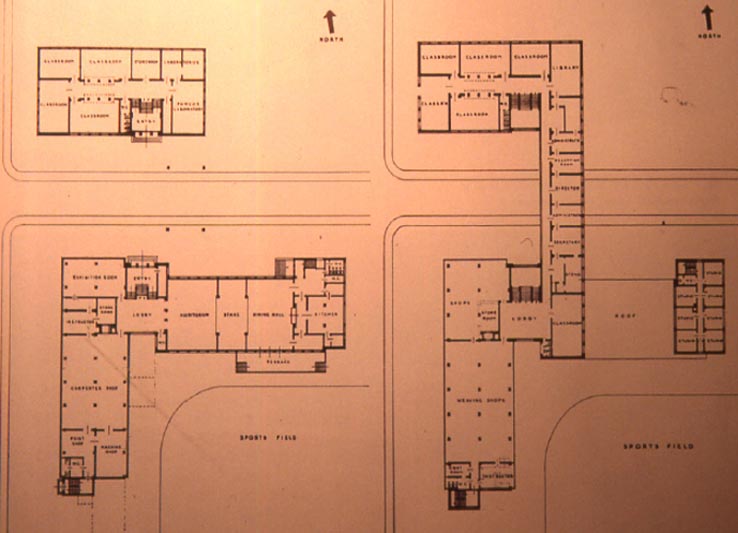

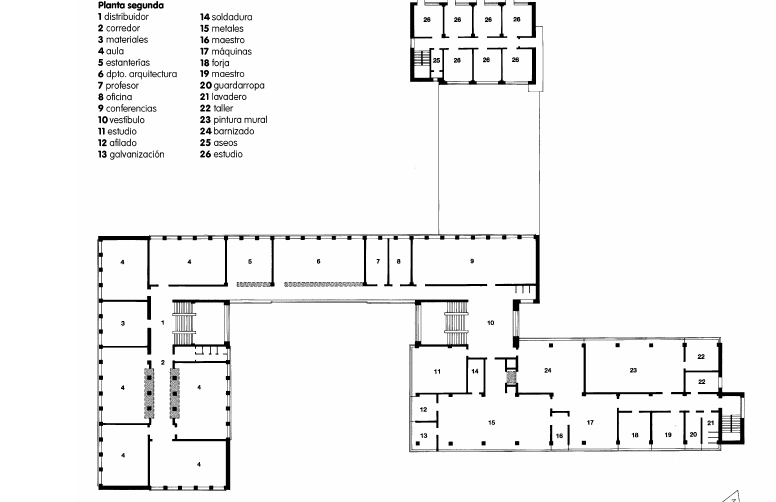

Three floors in the North part of the building which house classrooms and small laboratories.

Laboratories, classrooms, dining room and main auditorium

The main auditorium is like the heart of the Bauhaus because here can be seen, on a small scale, what was developed in those years and why it is where they held festivities. This compartment of the building is called the festive area and is comprised of the hall, the stage and the university dining room. The dining room and stage are separated by three folding doors, so that the whole section is actually one large space.

Kitchen and dining room

A window separates the kitchen from the dining room, it being a novelty at that time to be able to watch what the cook was doing.

Accommodation

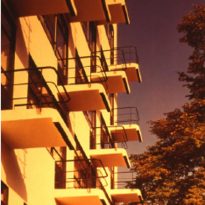

Six floors of 28 bedrooms, each 20m². All had a small balcony; a concrete slab which protrudes toward the open space.

On each floor, there were bathrooms and a small kitchen. In the semi-basement, the students had showers, a laundry with automatic machines and a gym. But the special thing about the accommodation was that the students had various possibilities for enjoying the good weather, as in addition to their balconies, there was a large roof terrace, surrounded by benches and partly covered.

This building is also the most solid volume, interrupted only on the East façade by the cantilevered balconies and on the West by the windows.

Bridge element

As well as connecting the distinct wings, it led to the office, Gropius‘ private workshop and a club or recreation area.

The bridge expressed the idea of an architecture freed from the ground, which does not impede urban circulation.

Structure

A steel and concrete structure forms the frame of the building, ensuring the unity of the complex and allowing for the existence of three different façades, built with very innovative though fragile materials such as glass.

The static construction is not as it may seem- completely in reinforced concrete- as only the frame is. The surfaces in between are mostly made of brick, as are the floors.

Materials

The Modernist movement enjoyed the possibilities of new industrial materials, such as reinforced concrete, rolled steel and large-scale glass panels.

Along with these new materials, the façades here also have a typical smooth, white plaster. However, they also have a base of rough plaster in grey. This base has an optical effect, as it gives the impression of the building being much lighter.

Apart from the plaster and its colour, the windows are one of the most basic elements of the façades. The Bauhaus’ windows are all steel-framed, without drainage, and with simple glass. They were never black, rather dark grey, which has the advantage that, from a distance, the frames cannot be seen. As such, the façade appears as a vast glass surface. We can see that the Bauhaus worked a lot with effects, whether light or optical illusions, but also with psychology, depending on these effects to influence the characters of those people who worked and studied within.

The corridors and stairs had magnesian floors, the offices had linoleum in various colours, and the walls were covered with lime plaster.

The cement used in the construction was very porous as it contained too much gravel, while the layer which covered the frame of the building had too little, which is why the iron frame has oxidised. The plaster used for the columns of the bridge which has remained as exposed concrete presents a relief which appears as though hammered, something which was unusual in modernist works.

A detail which demonstrates that this was not only a functional building in the location of the spaces, but also in the sense of practical use, is that since the beginning a method for cleaning the many windows was planned, consisting of hooks fixed to the roof from which ropes for saddles could be hung.

The central heating consisted of radiators placed throughout the building and is a symbol of Bauhaus’ intention to cooperate with industry and make use of new technological systems. In some spaces, these radiators occupy the space which would be dedicated to the exhibition of a painting of the Barroque period, demonstrating the importance of the utilisation of industrial elements to the Bauhaus movement.