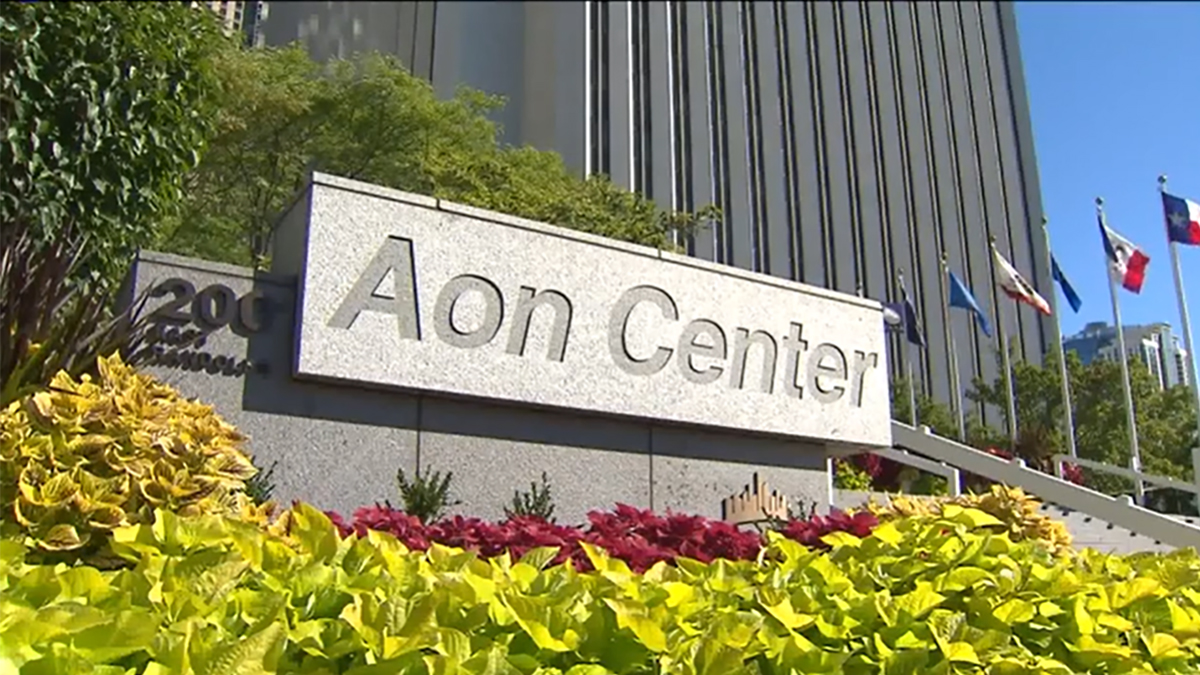

Aon Center

Introduction

The Aon Center was designed by the architectural firm of Edward Durell Stone in association with the Perkins & Will Partnership, and was completed in 1973.

It was first known as the Standard Oil Building, then changed it’s name to Amoco Building, and is currently known as Aon Center.

With 83 stories and a height of 346m, it was the tallest building in Chicago and the fourth tallest in the world at the time of its completion. It was later surpassed by the Willis Tower, the Trump International Hotel and Tower and the St Regis Chicago.

Change of name

The Standard Oil Building was built as the new headquarters for Standard Oil Company of Indiana. In 1985 the company rebranded as Amoco and the building also changed its name. The next change name came in 1998, when the property was sold and renamed the Aon Center in honor of one of its major tenants.

Perhaps its various names have kept the building from gaining the same iconic status as other Chicago high-rises. However, even as newer structures have sprung up nearby, the Aon Center remains an elegant and timeless piece of modern architecture that graces the city’s skyline.

Location

The Aon Center is located in the Chicago Loop, 200 East Randolph St, the financial district of the city of Chicago, Illinois, USA.

The Chicago Loop comprises a rectangle formed by seven streets parallel to Lake Michigan between Jackson and Lake Streets and five vertical to the lake between Wabash and Wells.

Within walking distance are some of the city’s main tourist attractions, such as the Art Institute, Millennium Park and Maggie Daily Park.

Concept

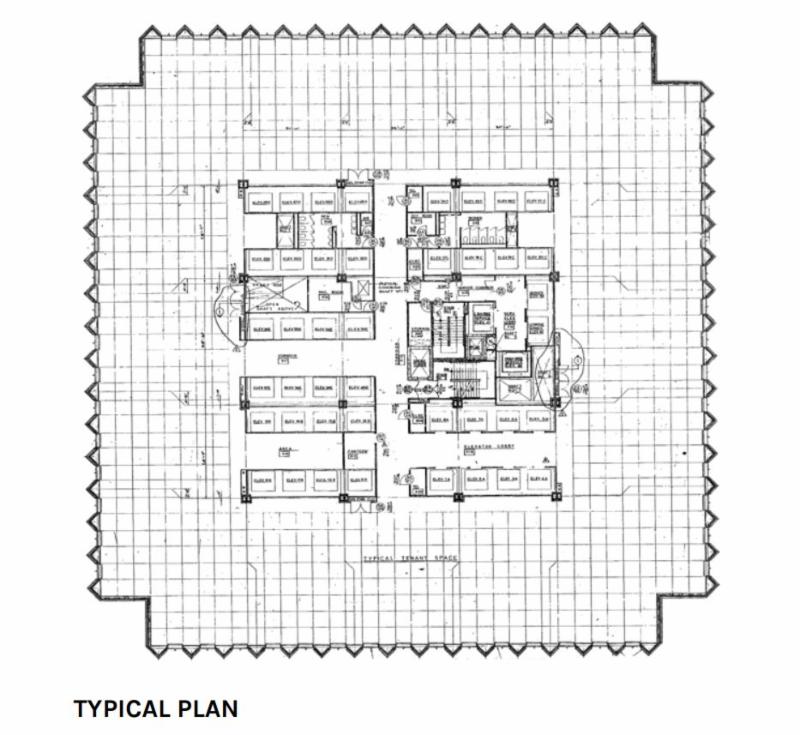

Stylistically the Aon Center reflects the classically inspired Modernism that East Coast architects such as Durell Stone and Philip Johnson embraced in the 1960s and 1970s. Structurally, however, the building is pure Chicago style, being a framed tube, a structural method first introduced in Chicago in the early 1960s and characterized by a center core and a series of perimeter columns connected to the core with spandrel beams that allow column-free floor plans.

Modern architecture is generally characterized by the simplification of form and the creation of embellishments from the structure and theme of the building. Gaining popularity after World War II, architectural modernism was adopted by many influential architects and architectural educators, and continues to be a predominant style for institutional and corporate buildings.

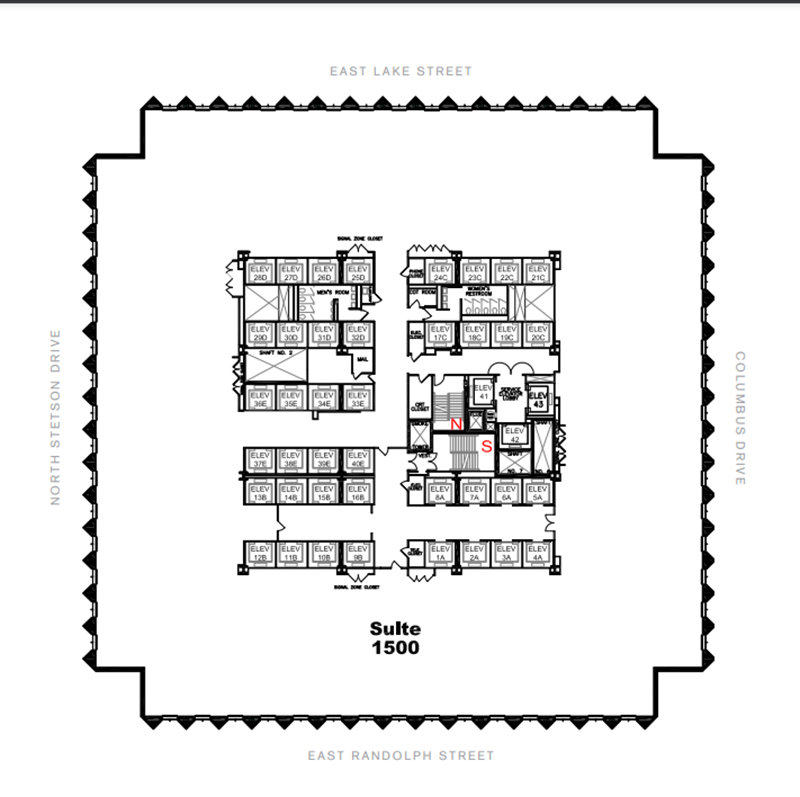

Spaces

The building occupies only a quarter of the lot, the remainder being a two-level landscaped plaza. It is the only building in the shape of a regular box over 300m high so far, and the tallest without antennas, spires or other elements on top.

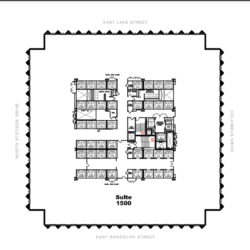

Its layout sets the standard for today’s corporate office offering top-notch amenities as well as panoramic skyline and lake views. It has a Conference Center with four rooms that can accommodate up to 80 people, a messaging center, an Auditorium located on level 1 with capacity for 205 attendees, and a luxury gymnasium on the 70th floor, among other services.

On the first floor of the building we find several retail stores, mainly dedicated to the supply of office materials for the tenants occupying the tower.

Public square

Surrounding the building is a two-level public plaza designed by landscape architect Edward Durell Stone Jr. It opened in 1974 as part of the transformation of the rail terminals into a mixed-use urban development called Illinois Center.

The landscape comprises raised walkways bordered by flagpoles on the east and west sides of the building, with an enhanced pedestrian entrance, a driveway to the north, and a sunken plaza to the south at the main entrance to the building. A 55m long waterfall, which conceals the ventilation ducts, falls into the pools bordering the square.

At street level, the garden is adorned with benches, glass-roofed pavilions, garden beds, water features, and areas shaded by large trees.

In 1974 Standard Oil commissioned sculptor Harry Bertoia to create a kinetic artwork to be placed in the water plane at the center of the plaza (372m2). With eleven sets of brass and copper rods of different sizes. The sculpture flexed in the wind, colliding with each other and resulting in resonant tones.

In 1994, architect Wojciech Madeyski and the landscape architecture firm Jacobs/Ryan Associates redesigned the sunken plaza: the rectangular pool was replaced with a circular fountain and performance area, gazebos were added, plantings were renovated, and Bertoia’s sculptures were reconfigured. Today a component of the sculpture remains, now located on the west promenade.

Parking

The building can park more than 679 cars in the five levels of subway parking available to the public. The garage can be used by the building’s tenants, their guests, and visitors to area attractions.

Structure

The architects used, a simple 59.15×59.15 rectangular framed tube structure with a relatively new tubular steel frame. This structural steel system with V-shaped perimeter columns is more resistant to earthquakes, reduces sway, and minimizes column bending.

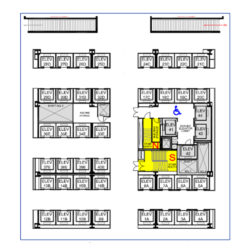

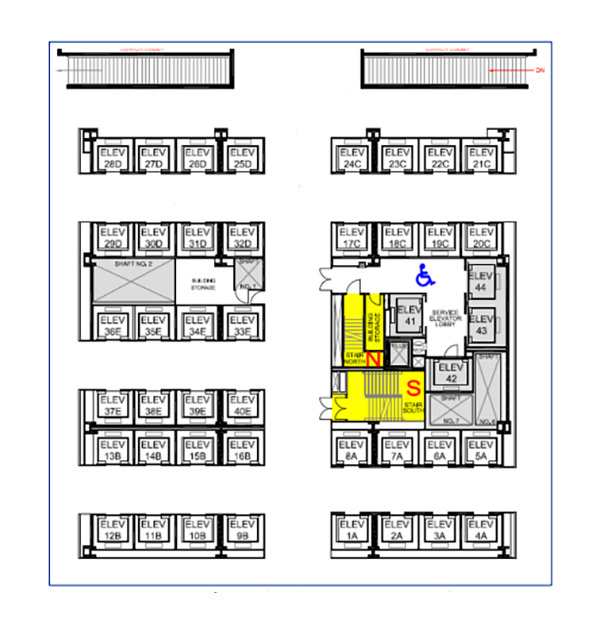

Elevators and other services are grouped in the core, while the perimeter columns define an outer tube. The tower has 50 elevators, some of them with double platforms, and several service stairways. The inner and outer tubes are joined by trussed beams that support the large open floor slabs, and the entire arrangement provides the structure that keeps the building standing. The height between floors is 3.86m.

The framed tube-based structure was related to the Willis (Sears) Tower, under construction at the same time.

The foundations are reinforced concrete poured in place, and reinforced columns, slabs and perimeter walls below grade.

The facades feature a curtain wall with 15 vertical bands of black windows on each side of the building, embedded between white triangular pillars. This non-structural curtain wall transfers horizontal wind loads to the main building structure through connections at the floors or columns.

Materials

Steel and V-shaped perimeter columns were used in the construction of its tubular structure.

The curtain wall is made of dark glass with metal frames and vertical bands of white marble that was later replaced by granite.

Carrara marble

Originally the numerous columns of the structure were clad with 44,000 slabs of white, 0.317cm thick, Carrara marble. Although the material was beautiful, it was cut too thin to resist the sudden Chicago temperature changes, and cracks started appearing over time. Heat causes a permanent expansion in this type of marble and while the external side expanded, the side facing the building did not. In the early 1990s, the entire building was clad with a much stronger granite.

The Carrara marble originally used was recycled in a variety of ways: as trophies for staff awards and as part of a garden at an Amoco refinery in Whiting, Indiana.