Wrigley Building

Introduction

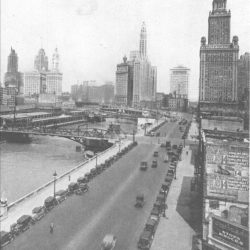

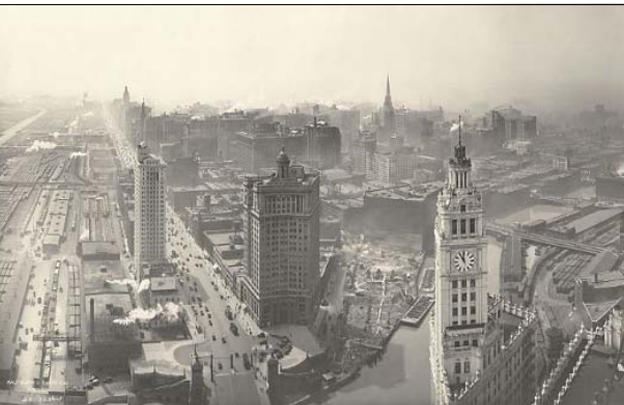

When Michigan Av. extended north of the Chicago River, it opened up a gritty landscape of small buildings and industry to a complete transformation. Chewing gum magnate William Wrigley Jr. started the boom when he decided to build a new headquarters for his company on an odd-shaped lot west of Michigan Avenue and just north of the river. It was the first, and arguably the best, of the buildings that have come to define the Magnificent Mile.

William Wrigley, Jr. commissioned the architectural firm of Graham, Anderson, Probst & White to design a building that would serve as a fitting monument to the company’s success. The firm drew on a variety of influences ranging from European classicism to early skyscraper development. The resulting structure served as the centerpiece for the new “Gateway to Chicago” created by the 1920 opening of the Michigan Avenue Bridge. As the first major commercial structure built north of the river, the Wrigley Building inaugurated the rapid commercial development of North Michigan Avenue during the first half of the twentieth century.

One of the important features of Daniel Burnham’s 1909 Plan for Chicago was to widen Michigan Av., formerly Pine St., north of the river and build a new bridge to connect the roadway on both sides of the river.

The iconic Wrigley Building was home to the Wm. Wrigley Jr. Co. for nearly 100 years, until it was sold in 2011 to a group of investors. In 2012 the Wrigley Building received official Chicago Landmark status.

Anecdotes

After its opening, the temple-like dome on the 26th floor of the Wrigley Building served as an observation deck for 360° views of the city as it rapidly expanded. The five-cent admission price included a stick of Wrigley’s gum,

Since then, the Wrigley Building has become recognizable around the world not only as an image of Chicago, but also for its place in popular culture and architectural history. In 1965 Frank Sinatra stated that “Chicago is…. The Wrigley Building”, 8 years after giant grasshoppers scaled the structure in the low-budget sci-fi film “The Beginning of the End”. The Art Institute of Chicago has a fragment of one of the building’s terra cotta finials in its archives, while the Canadian Centre for Architecture’s collection includes coins with the building’s image as souvenirs.

Location

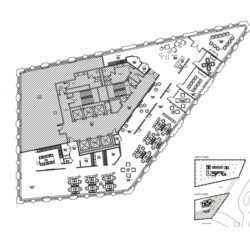

The early skyscraper is located at 400-410 Michigan Av, where it intersects the Chicago River. The building is known throughout the world as a symbol of the city of Chicago, reaffirming the city’s preeminence in both architecture and commerce, as well as marking the entrance to the Magnificent Mile, the city’s great commercial axis.

In the 1920s the street now known as the Magnificent Mile was little more than a country road called Pine Street that stretched north from the Chicago River, lined with docks, wharves, factories and railroad tracks.

Concept

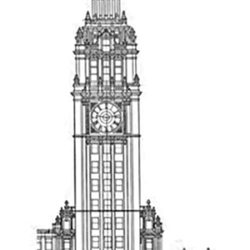

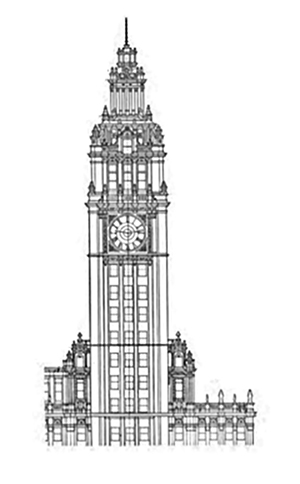

The site chosen for its construction called for a remarkable building and architects Graham, Anderson, Probst & White lived up to expectations. Modern in its height and steel structure, the facade of the Wrigley Building, however, carries the weight of history. The architects combined for their design the Spanish Neocolonial architecture materialized in the form of the Giralda tower of the cathedral of Seville, Spain, with details of the Beaux-Arts style and the French Renaissance.

As a young man, Wrigley visited the World’s Columbian Fair (1893) held in the city of Chicago and never forgot the famous “White City” and its nightly light displays. The color of the material widely used for the facades of the buildings gave it this nickname. Those memories live on in the building that bears his name. Six different shades of bright white terracotta become brighter as the building rises and its facade is illuminated at night in its twin structures.

The building was the first skyscraper built on the new grand boulevard and residents and visitors alike stop at its plaza and mark time with the tower’s clock.

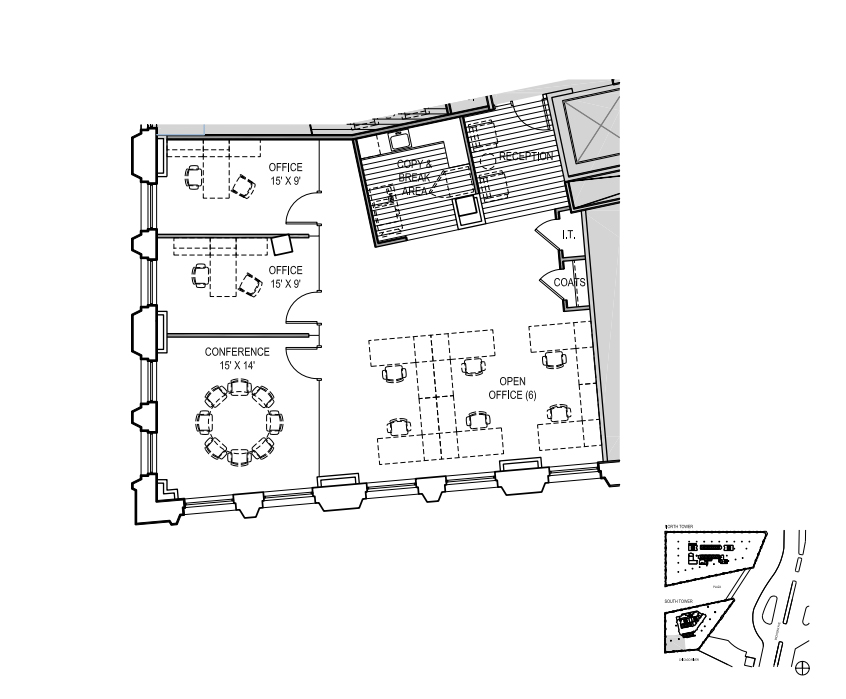

Spaces

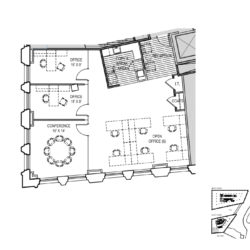

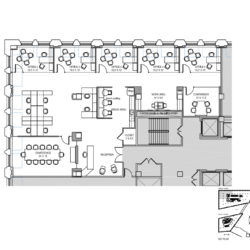

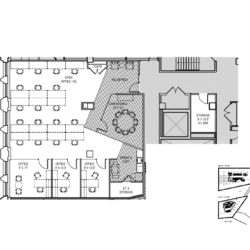

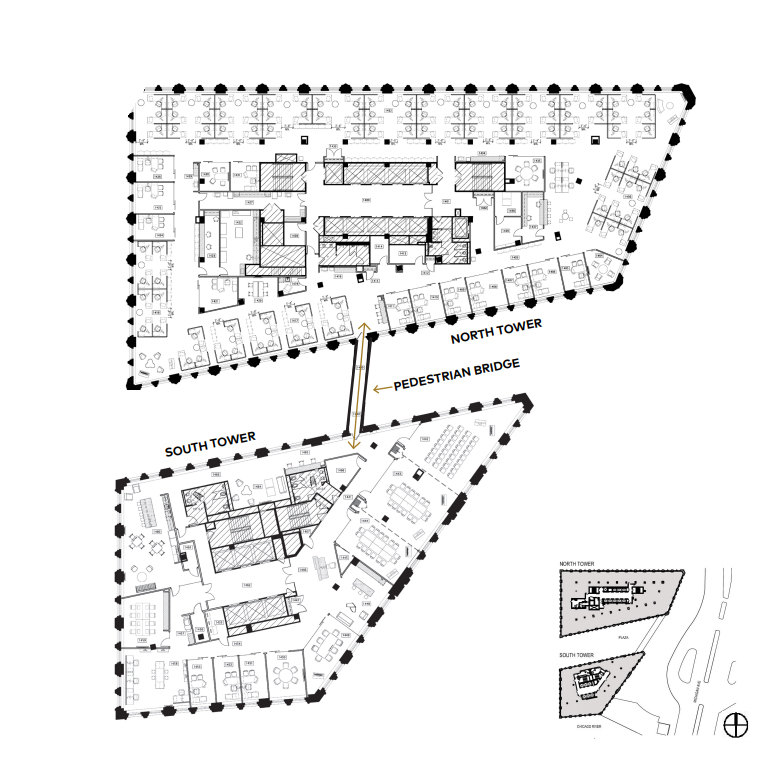

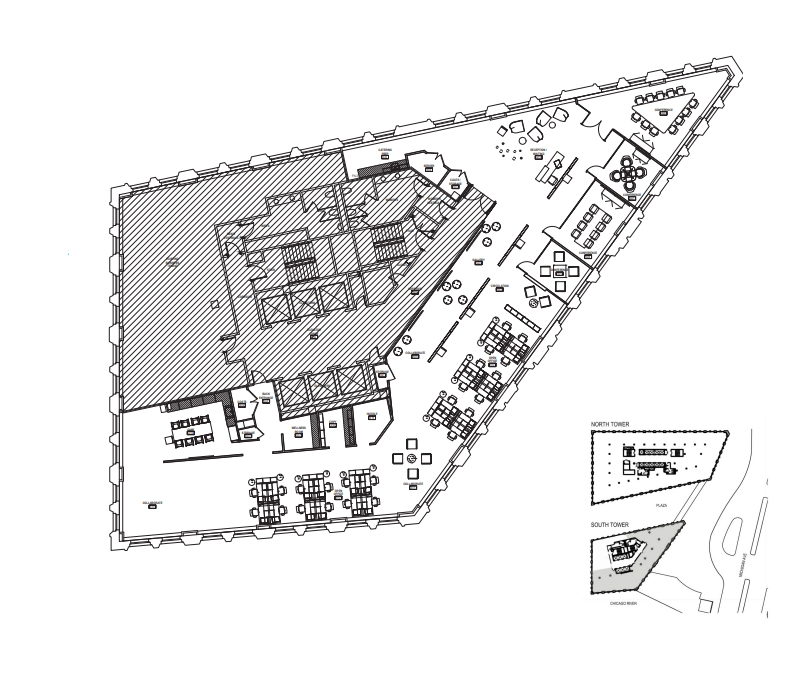

The office building is composed of two volumes, the south building and the north building. At 121.31m high, a singular flourish crowning the first building was just 61cm below the maximum height allowed by Chicago building codes at the time, 121.92m.

South building

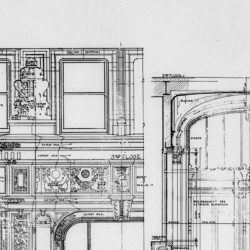

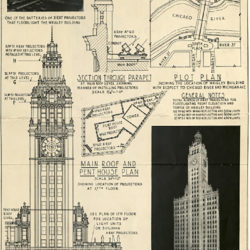

The first completed tower, the one located to the south, is crowned with a four-sided tower with a 5.97m diameter clock in each of the four directions, on the 23rd floor where the vertical windows end. Above the clock faces, the tower ends in an exuberant display of ornament: the crowning with a ring colonnade and a dome from which rises a 10m silver spire. It is the tallest building in the complex, with 30 floors, and was completed in 1921.

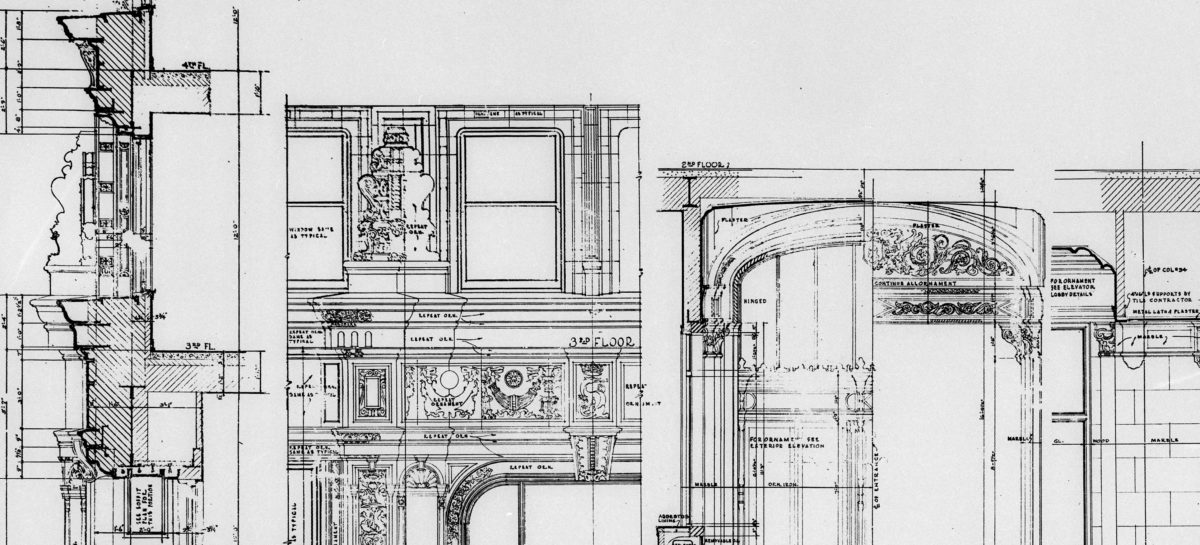

The three lower floors form the base of the building, which is marked at its center by a tall vaulted entrance framed by recessed columns. Continuous pillars and mullions give a subtle vertical emphasis to the main mass of the building, an emphasis that is strongly expressed by the tower. A parapet tops the main block and a setback between the seventeenth and nineteenth floors provides a transition between the main block and the tower.

North building

The north building is a 21-story structure that was added to the south building in 1924.

The new structure, also designed by Beersman of Graham, Anderson, Probst & White, more than doubled the footprint of the original structure. It is similar in scale, design and materials to the first building. It also consists of a 16-story main block topped by a tower.

To maintain uniformity throughout the streetscape, the east façade of the annex was set back to align with the south building, creating an even more spacious plaza fronting Michigan Avenue.

Footbridges

The two structures are connected by a series of walkways, one of which is at street level. There are also two elevated walkways linking the buildings, one on the third floor and one on the 14th floor added in 1931 to connect to the offices of a bank in accordance with a Chicago statute regarding bank branches. The two towers, not including the levels below Michigan Avenue, have a combined area of 42,125.3 m2.

Wrigley Plaza

Between the two structures and at street level is the Wrigley Plaza. Although the Plaza was part of the original plans for the building, it was not built until 1957.

Restoration

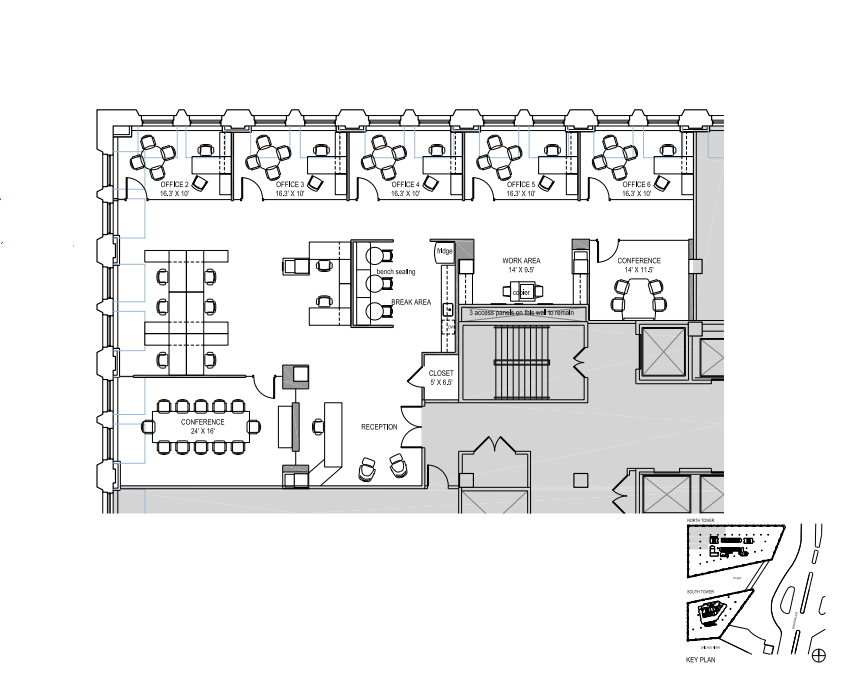

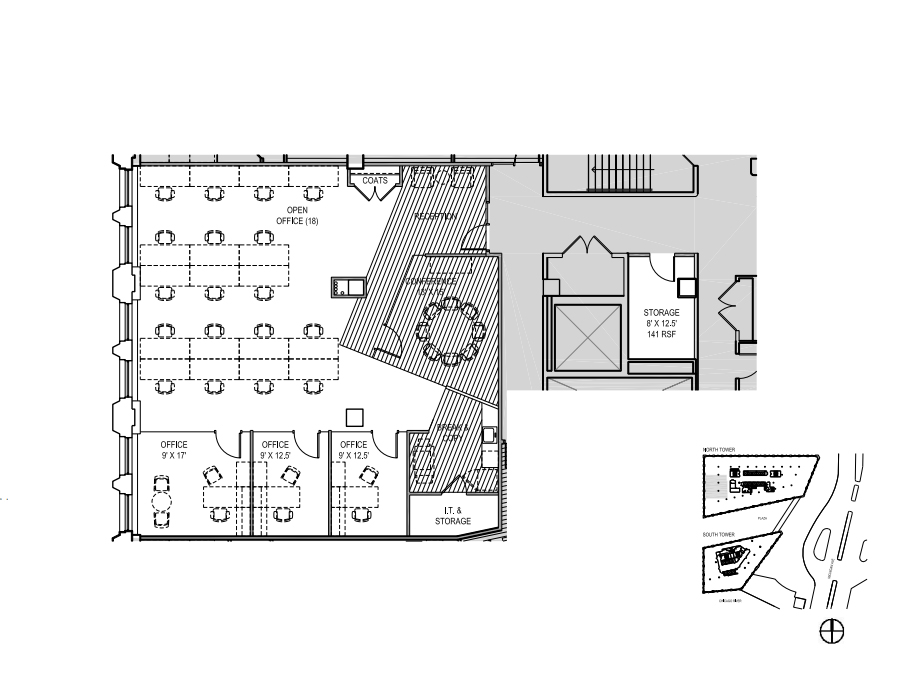

In 2011 the Wrigley Building was sold to a group of investors who sought to renovate the building while preserving its name and historic integrity. The project was carried out by the architectural firm Goettsch Partners.

The most historically sensitive work focused on the exterior, lobbies, and plaza of the building, while the upper floors were completely renovated to serve the new office users of the 21st century. To make the building more attractive, a “green wall”, a cafeteria, a gymnasium, and an infirmary room were added.

One of the most significant efforts was the removal of the screen wall between the two towers at ground level, which also involved structural remodeling and terracotta restoration.

The entire 1950s plaza was demolished down to the structural steel. The area was reconstructed using new pavers in a consistent color palette and materials.

Within the towers, the main public areas were also renovated. In particular, inside the building’s lobbies. Remnants of poor renovations made in the 1980s were removed and the original designs were restored to the extent possible using 1920s marble and mahogany. The historic corridors were largely preserved, including the marble walls and floors, as well as the original doors. In addition, almost all of the building’s windows, more than 2,000, were replaced and security systems were replaced or upgraded.

Structure and materials

Charles Beersman, the Graham, Anderson, Probst & White architect who led the design, gave the south building a trapezoidal body that takes full advantage of its angular site. On top of this block, he placed a huge 12-story tower.

Structurally, the building is a concrete-encased steel frame with caissons anchored to bedrock. The main body of the building rises 64m, which, along with the 57.30m of the tower brought the building to within 0.61cm of the height limit allowed by the city in 1921 for building construction in the city of Chicago.

Vertically, the composition of the building is the most common among commercial buildings of the time: a base, a shaft, and a capital. The two structures are connected at several points by elevated enclosed walkways, including a stainless steel covered passageway linking the 14th floors.

The Wrigley Building was the first office building in the city of Chicago to be air-conditioned.

Terracotta

The building is clad with glazed terracotta pieces, which provides its gleaming white facade although there are actually six slightly different shades of glazed terracotta tiles, from grayish white near the base to a pale cream color at the top, to catch the eye. Sometimes the entire building is hand-washed to preserve the terracotta, which glows at night under spotlights. It is one of the largest and most ornate terra cotta skyscrapers in the city, with over 250,000 pieces of architectural terra cotta originally designed and produced by Northwestern Terra Cotta Company.

The façade is also decorated with figures molded from the same material, a lively mix of ornamental details borrowed from the French Renaissance style, including mythical figures such as cherubs, phoenixes, knights in armor, eagles, lions or other natural elements such as seashells, vines and geometric shapes.

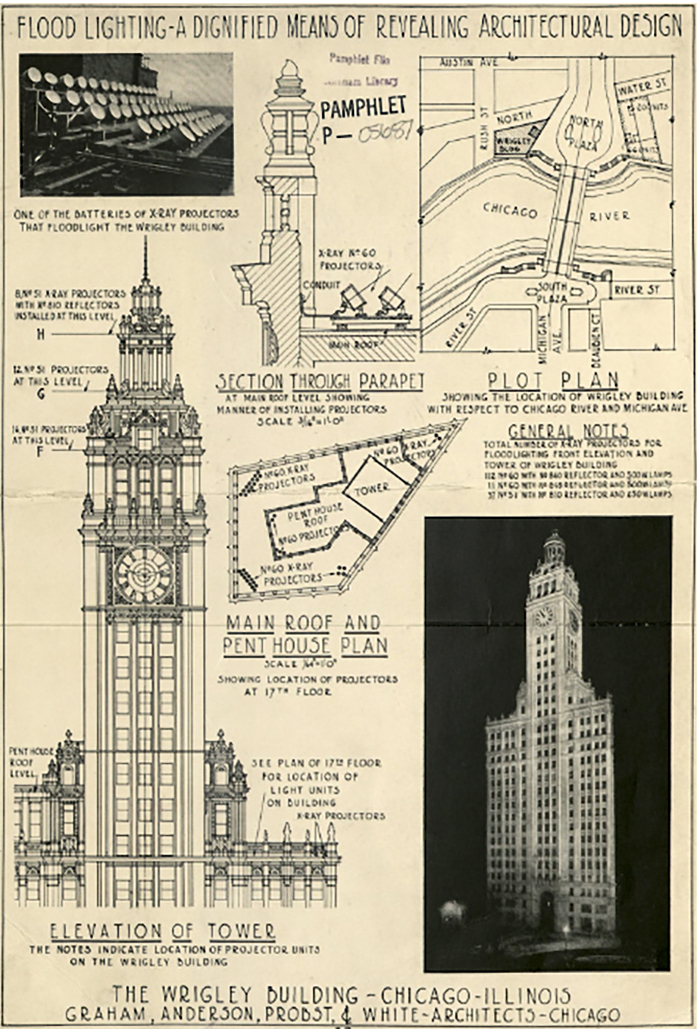

Night lights

It was one of the first skyscrapers to use an extensive and innovative lighting system, composed of floodlights, which was later replaced by modern lighting.

The night lights were first turned on in 1921. The lighting consisted of about 116 1000-watt metal halide lamps installed on the south side of the Chicago River, seven lamps at street level, and 16 halide lamps to the west of the building. The gradual illumination of the building towards the top was achieved by the 62 lights that are mounted on the building itself.

Originally, these state-of-the-art floodlights provided a bright light that bathed the building, with the strongest light concentrated on the tower. Except during World War II, a period during the winter of 1971 when a new lighting system was being installed, and during the nine months of energy crisis between 1973 and 1974, the Wrigley Building has been one of Chicago’s brightest nighttime sights.