Törten Estate

Introduction

Between 1926 and 1928, the Gropius studio built terraced houses in the suburbs of Dessau. The client was the City Council, who wished to resolve the shortage of social housing. The project was completed in three stages and, in those, the architect applied all forms of rationalisation possible, empirically putting to the test on a grand scale his ideas on rationalised and standardised construction of houses.

In 1919, Walter Gropius had stated that “the primary objective of all plastic activity is its integration in construction”, but in the vacuum left by the Bauhaus not having an architecture department, it was not acted upon until 1927. From his private studio, Gropius took responsibility for publicising the “commercialisation” of the process of mass construction and began to circulate a film which demonstrated the work.

Location

Törten Estate was developed in Heidestraße, a Southern suburb of Dessau, Germany.

Concept

Although various Bauhaus workshops participated in the construction of the Törten Estate, it was not a project of the school but of the private studio of Walter Gropius. Even so, the estate is an excellent example of the new orientation of the Bahaus towards large scale industrial manufacture and its unconditional acceptance of the modern world, far removed from the enthusiastic romanticism of the guild of earlier times.

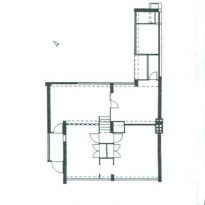

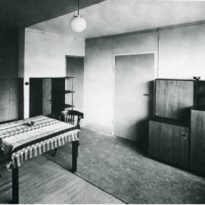

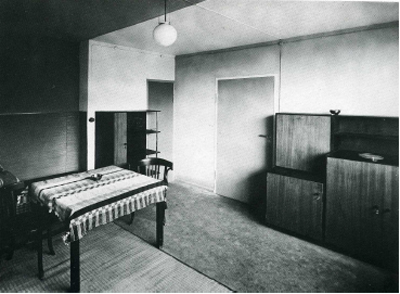

Once Meyer took up the direction of the Bauhaus and alongside Gropius in Berlin, the architectural investigation started on an unusual path, searching for the biological essence of the human being and its reactions, by studying the behaviour of primates in enclosed spaces. They also investigated ways to eliminate irritating noises and odours, and the duration of sunlight throughout seasons. These investigations resulted in the block-like rooms of the Torten Estate, where space is minimised in floorspan as well as height to maximise usable space. They tried to use materials and repetitive structures so that the cost of construction would be significantly lower than normal. It was the moment in which the functionalism so advocated and propounded by the avant-garde reached its zenith.

Spaces

The works were as meticulously organised as a factory and constituted a model example of “Taylorism”, which had previously been promoted by the municipal architect of Berlin, Martin Wagner, and tested in the construction of housing estate projects within the city. The entire working process was pre-calculated precisely and fixed in writing.

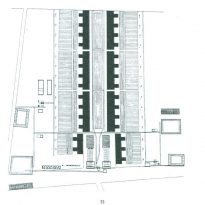

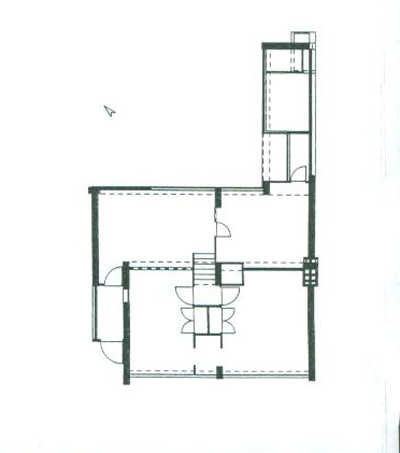

What characterised this group of houses was not the needs of their future occupants, but the requirements of the industrial production and the machinery. Thus the projected plan of the estate was defined by the reach of the arms of the rotating cranes.

To begin with, they built 316 houses, type Sietö I, with gardens and austere appearances, above all in the interiors. They also constructed a block of apartments with shops below in the Konsum building.

Sietö I Houses

In the first phase they had many setbacks, such as windowsills which were too high on the upper floor, corridors between rooms which were not high enough, absence of an entry hall, barely functional kitchens, or heating which scarcely worked.

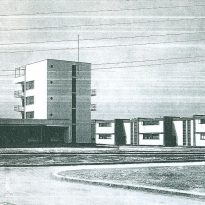

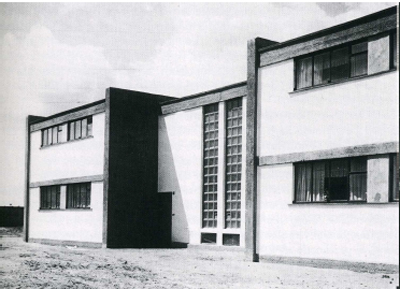

However, the formal design of the outer façade was worth consideration. Always within the modesty of its means: the combination of horizontal window sashes, vertical planes in glass brick and brick-clad dividing walls between the houses offered a certain warmth.

Konsum Building

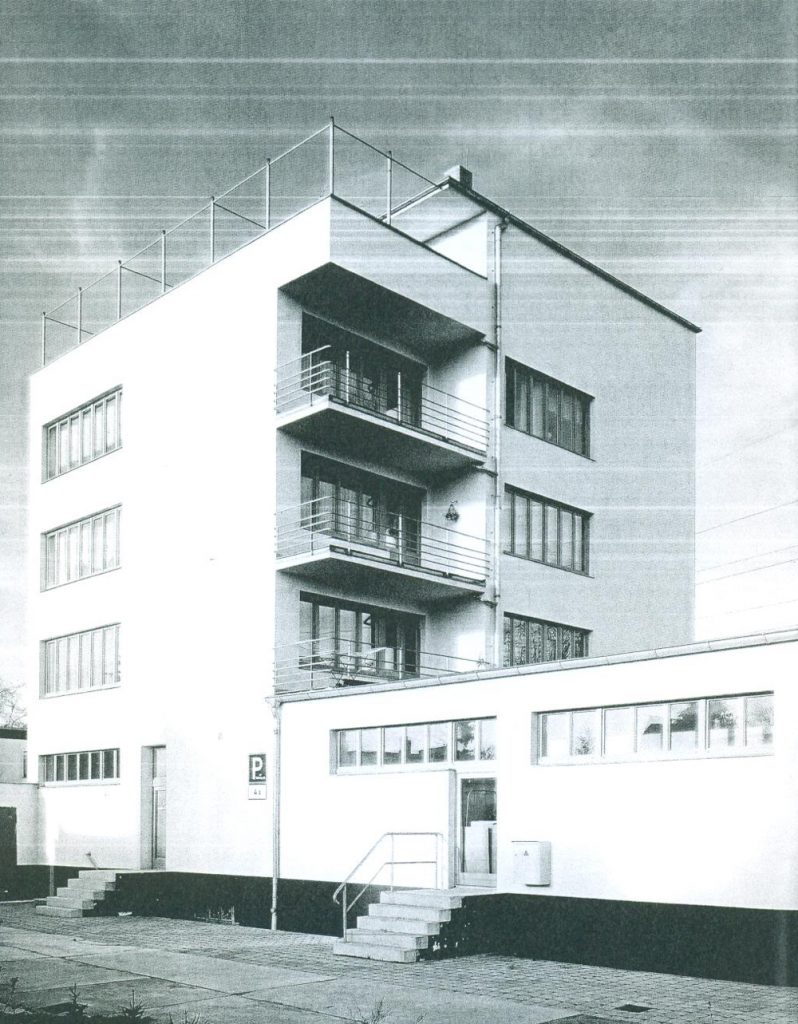

The building was a dominant focal point within the complex of flat roofs: a five floor vertical piece for the consumer cooperative, Konsumverein. On the ground floor, there was a wide rectangular space where the food shops were located: a butcher, a café and a social centre. In the tower were homes and a laundry.

In 1930, Meyer extended the estate by five blocks of houses in a row.

Materials

The houses were built with standardised pieces of concrete, made on site. Likewise the blocks of artificial stone, made from a base of the cinder-concrete used for the walls, and the reinforced concrete beams for the slabs were manufactured directly on site, in a process similar to that of a production assembly line.

This system permitted them to reduce the construction time to an average of three days per house, and lower their costs. In this way, the same workers could then afford to rent them.

They used glass bricks in some ornamental walls and red bricks as cladding for others, most importantly for the dividing walls between the houses.