Seagram Building

Introduction

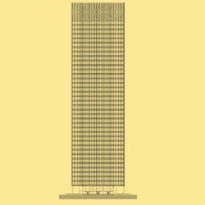

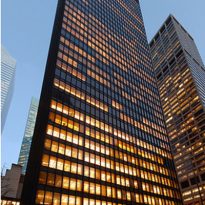

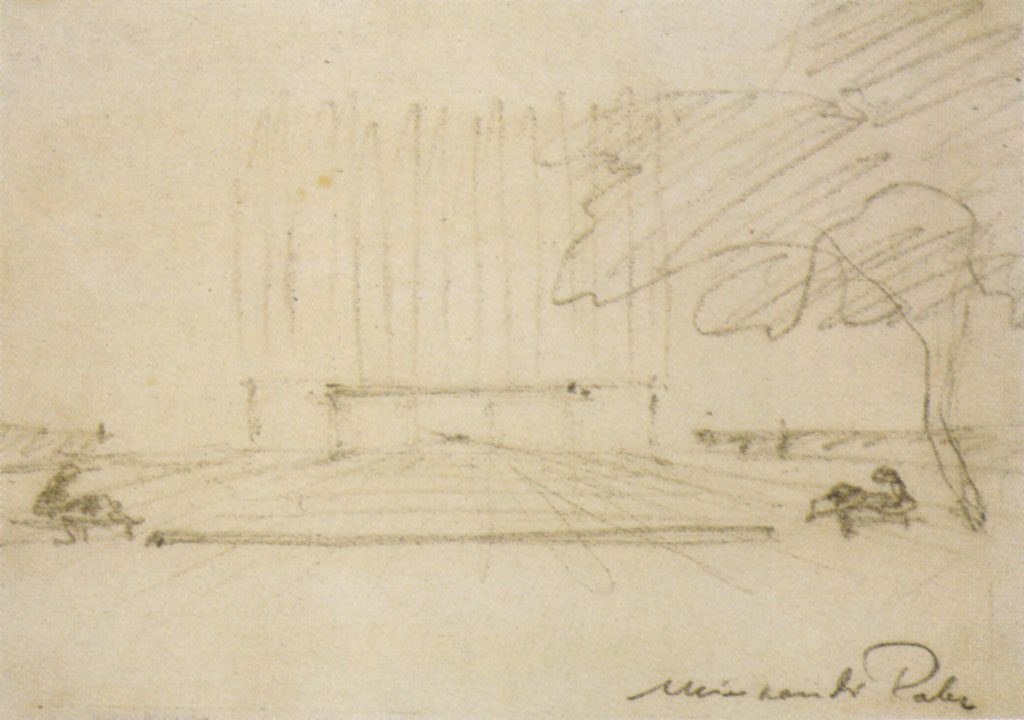

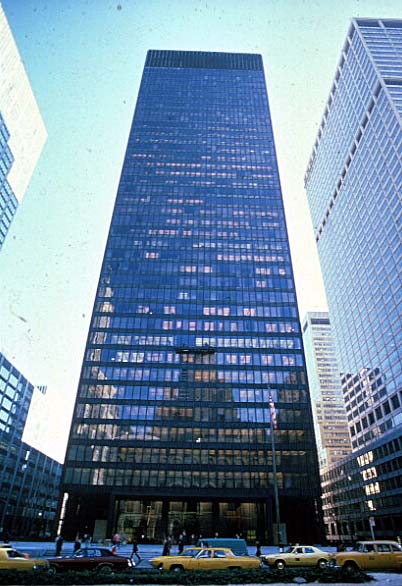

Designed by Mies van der Rohe, in collaboration with Philip Johnson, the Seagram Building stands as the archetypical model of office in the International architectural style.

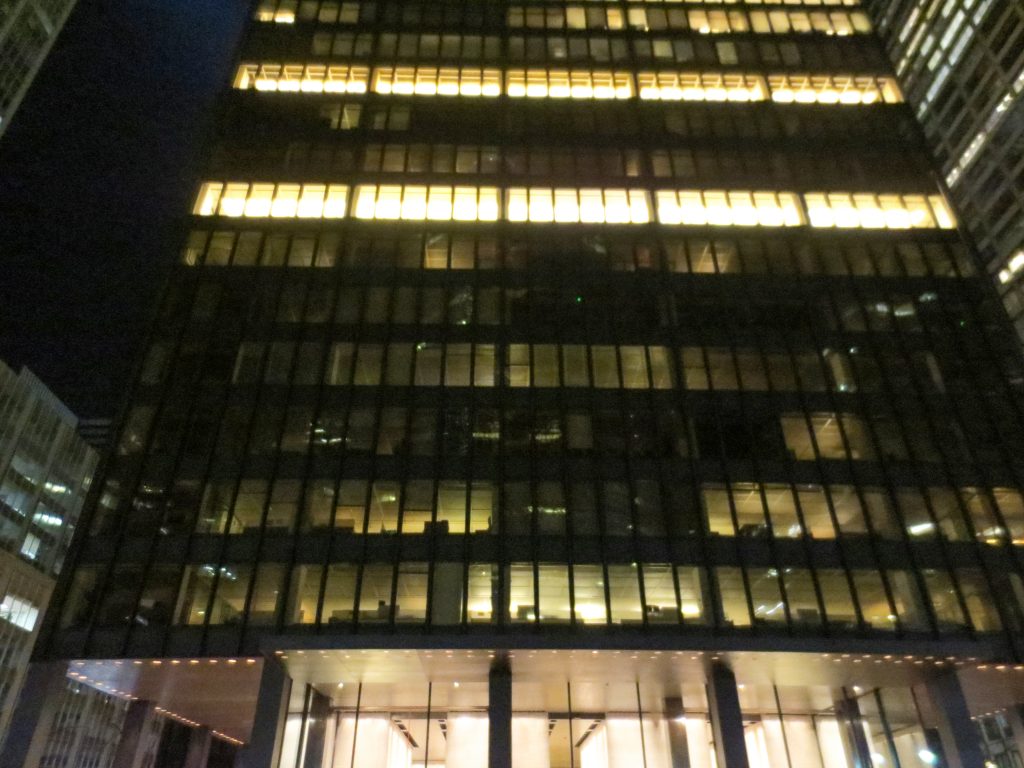

Completed in 1958 in New York City, the building epitomizes Mies‘s rigorous journey of expression through minimalism, offering a transcendent experience devoid of ornamental distractions.

This icon of 20th-century architectural elegance served as the headquarters for the Seagram corporation, once run by a magnate who had profited from the prohibition era’s illicit alcohol trade.

Location

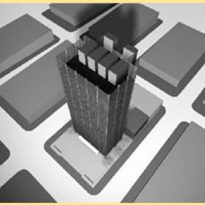

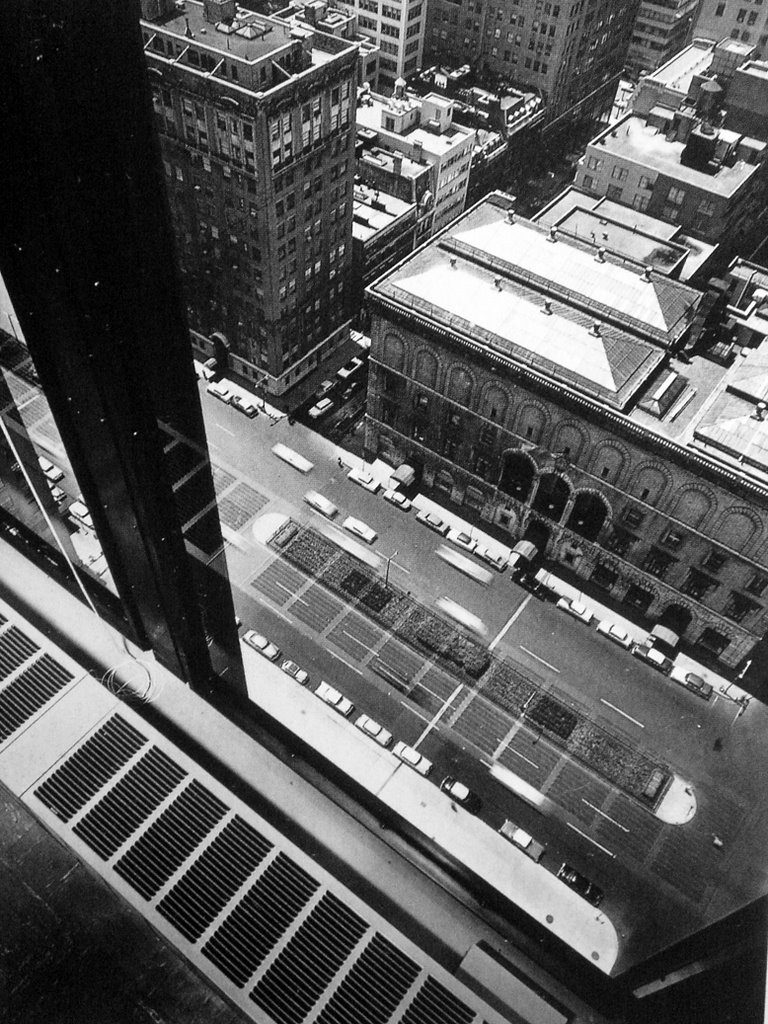

Positioned in the heart of Manhattan, the Seagram Building graces 375 Park Avenue, situated between 52nd and 53rd Streets.

Concept

The Seagram Building encapsulates Mies van der Rohe‘s famous adage, “less is more.” It’s a synthesis of the rationalist principles he taught and implemented at the IIT, the emerging International Style of the 1950s, and the architectural innovations of the Chicago school.

Spaces

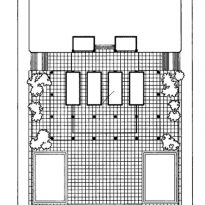

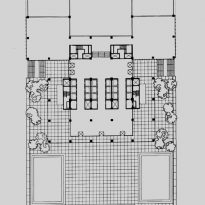

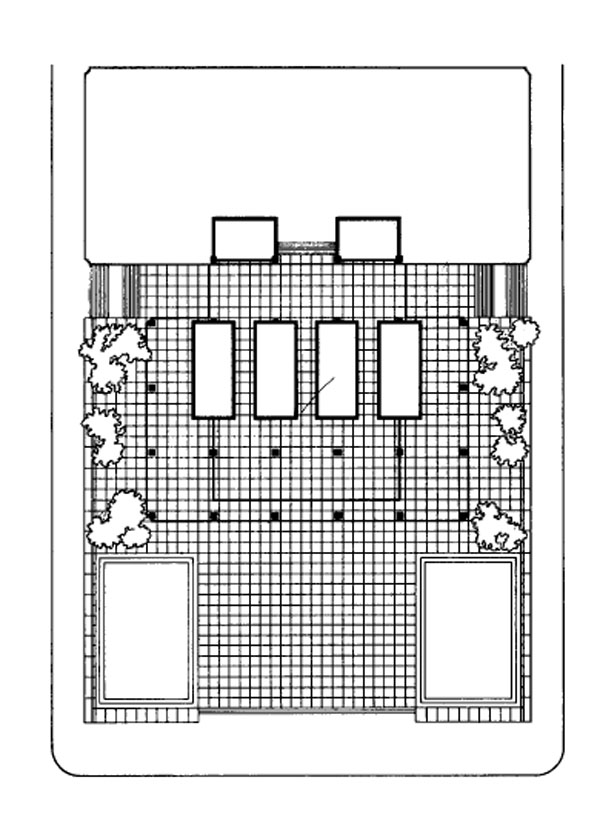

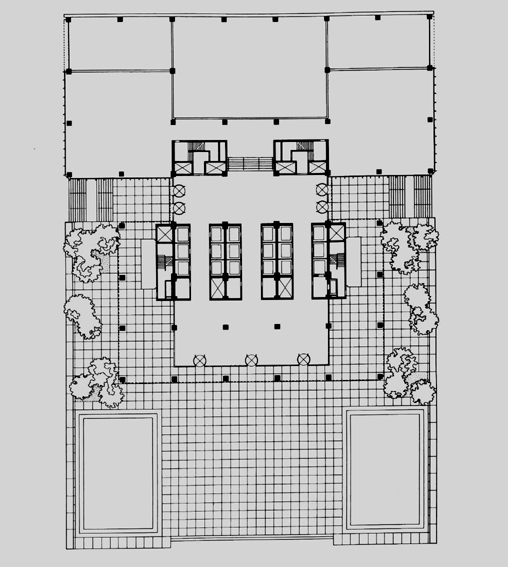

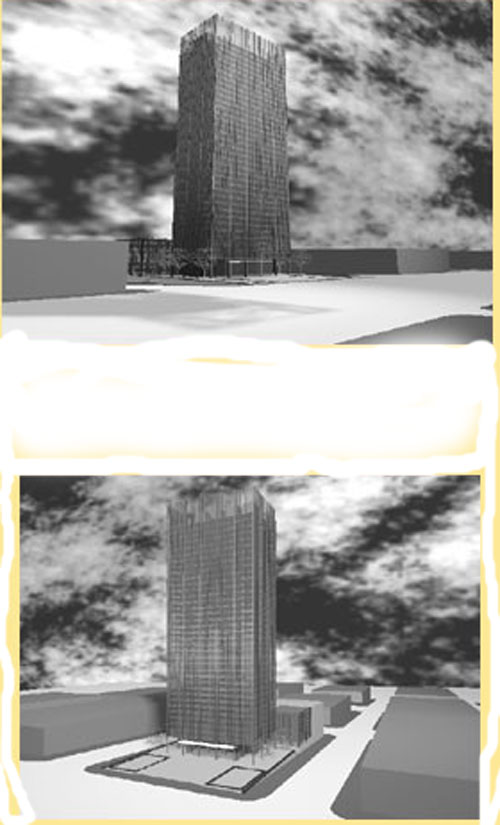

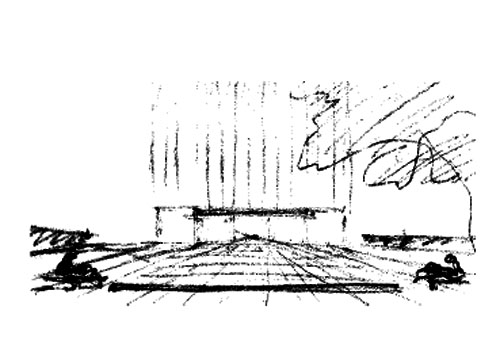

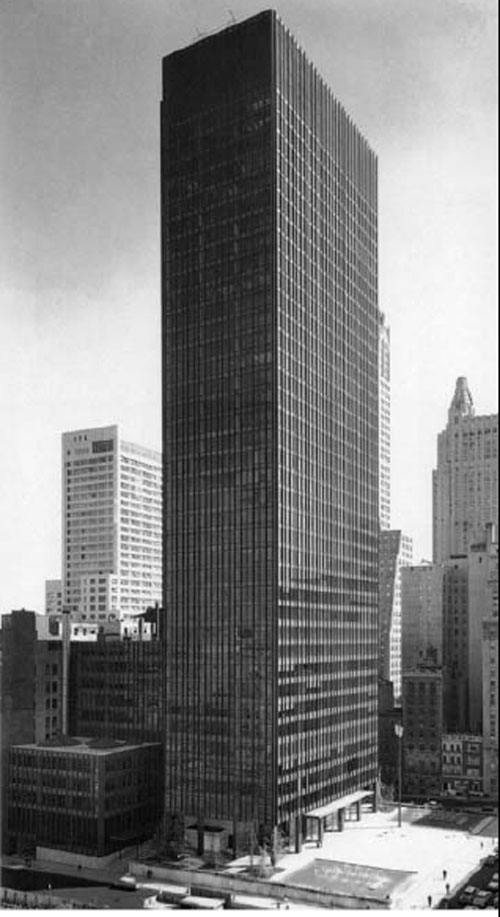

A standout feature is its innovative use of an open plaza. Rather than consuming the entire lot, Mies elected to set the building back, creating a plaza that enhances the sense of scale. This intentional design decision facilitates a juxtaposition between occupied space and void, a contrast particularly notable in the dense urban context of New York City. The plaza serves to highlight the building’s stature while offering a refreshing openness amidst Manhattan’s skyscrapers.

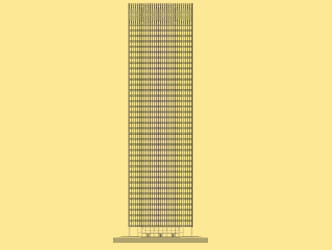

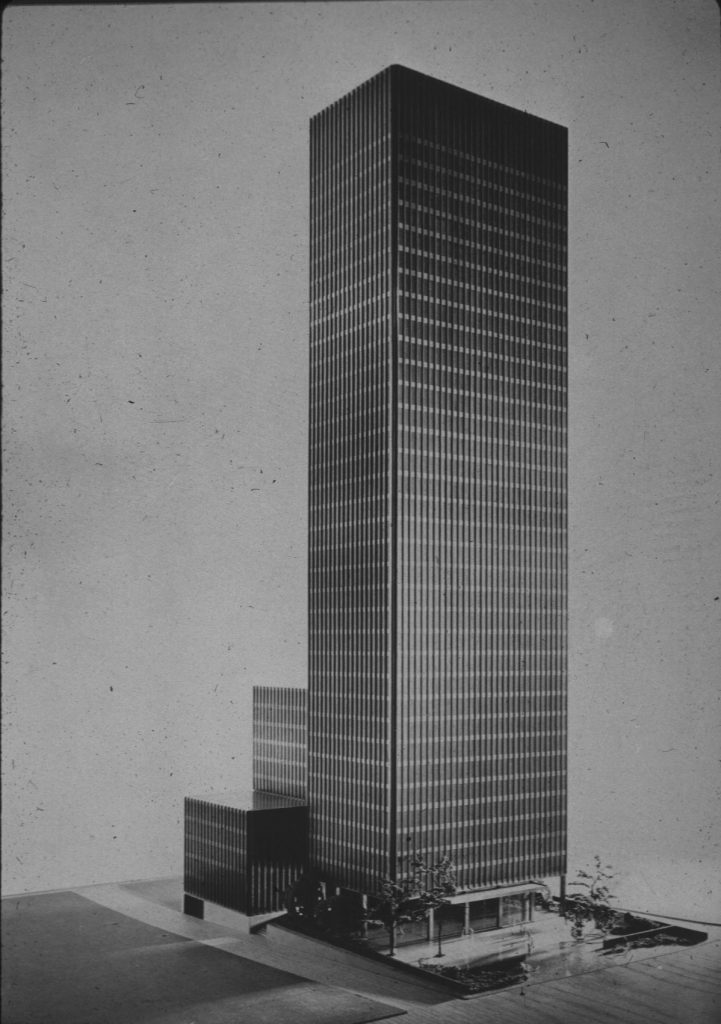

Structured much like ancient columns, the Seagram Building boasts a base, shaft, and capital. The majestic entrance is complemented by fountains and a grand stairway, evoking classical antiquity.

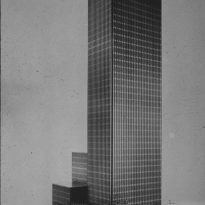

Rising to a height of 157 meters, the building spans 39 floors, all dedicated to office spaces.

Structure

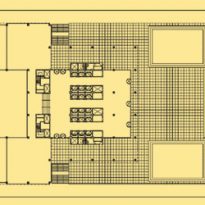

Layout

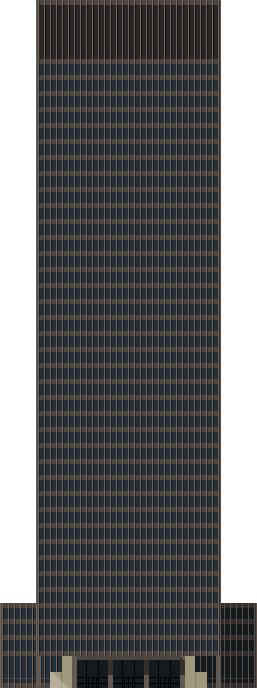

The Seagram Building, much like Mies‘s earlier Lake Shore Drive Apartments, follows a design grid that breaks down the floor plan into a 5×3 module of square structural units. However, it’s in the building’s elevation where Mies‘s design truly achieves expressive perfection, emulating a column’s classic three-part design: base, shaft, and capital.

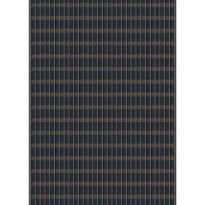

Facade

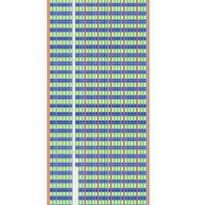

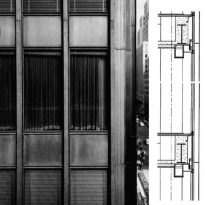

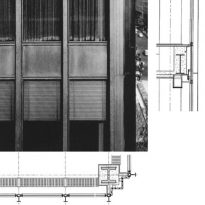

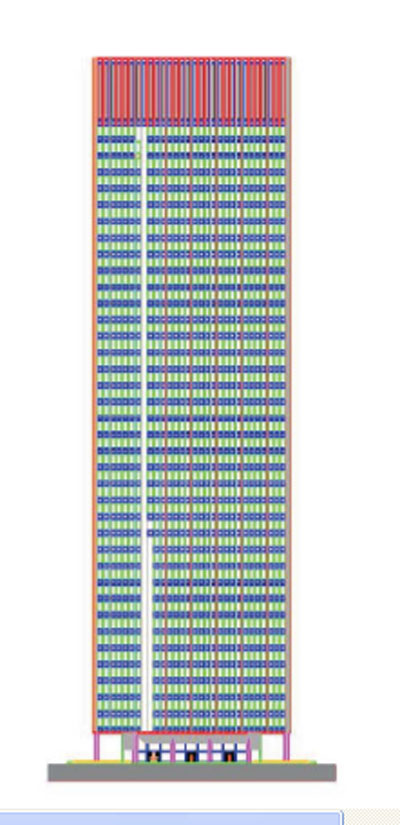

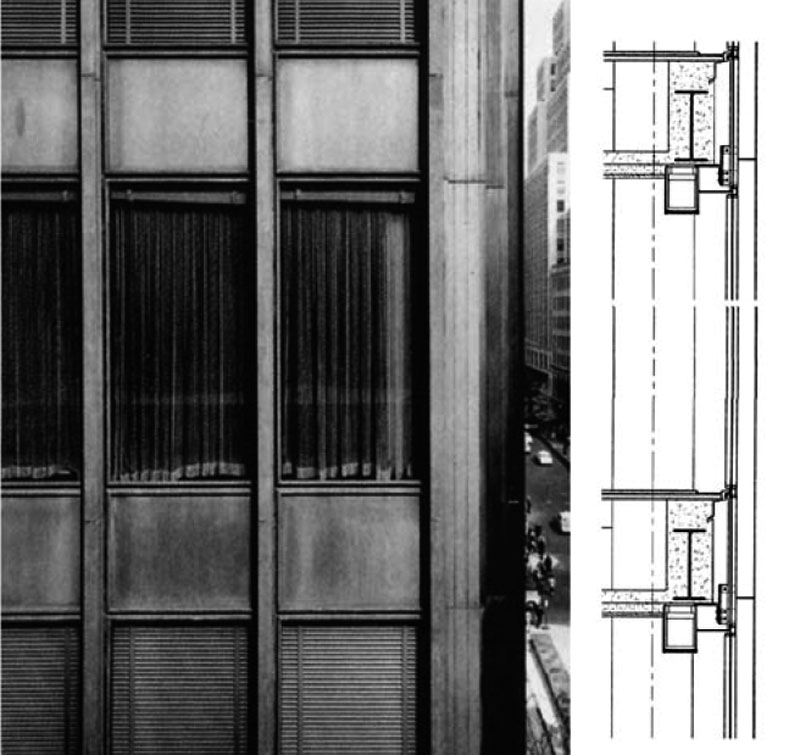

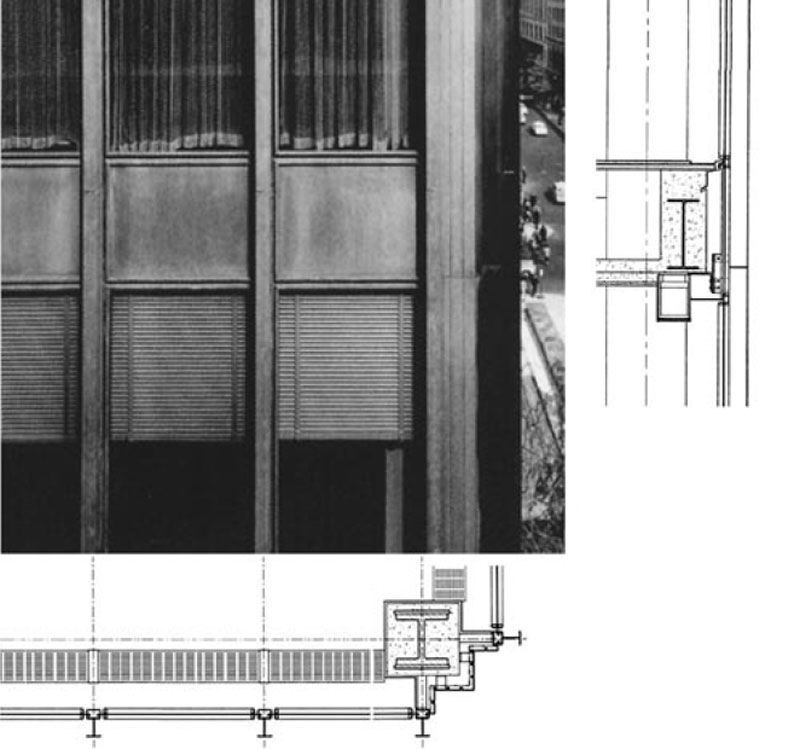

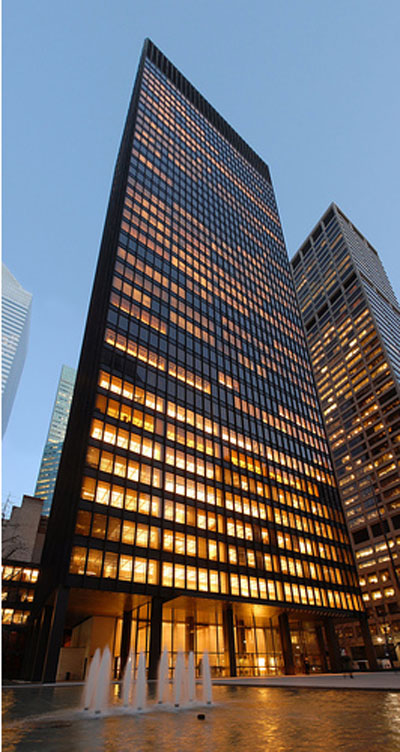

The Seagram Building’s exterior reveals the structure in its facade, where decorative details blend seamlessly with functional elements. Made up of steel beams and bronze columns, the facade frames the building’s extensive glass paneling. Interestingly, these bronze columns were initially planned to be steel, but a decision to use bronze was made after the Seagram company voiced concerns over budget constraints.

Blinds

A building of this size has hundreds, if not thousands of windows, each of which would need its corresponding curtain, which traditionally the user would be able to adjust to their liking. To maintain visual consistency, Mies incorporated blinds that could be adjusted to only three positions. The mingling of the external bronze profiles with the tinted glass, primarily designed to moderate internal temperatures, imbues the building with an understated elegance.

Materials

The building’s facade marries curtain walls of glass with elements of bronze. Due to fire safety regulations enforced in 1954, Mies used concrete for the building’s structural elements, both inside and out. Mies‘s dedication to architectural refinement is exemplified in his choice of materials: the muted glow of the bronze frames contrasts beautifully with the rosy tint of the glass curtain walls. This lends the Seagram Building a distinctly New York charm, distinguishing it from its more austere predecessors.

At the street level we can also find some Travertine marble, which Mies loved to use since the times of the German Pavilion in Barcelona, and Pink marble.

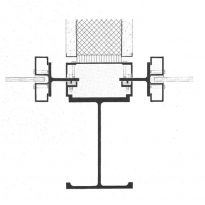

Profiles

In many of Mies‘s American designs, the exposed steel profiles are more symbolic than functional, primarily due to fire prevention regulations mandating the fireproofing of steel. Thus, the visible “structure” symbolically represents the hidden reality.

Mies utilized standardized steel shapes, specifically the I, H, and L profiles, to craft by welding, creating profiles that echoed the precision and elegance of classic architectural designs. These exposed profiles in the Seagram Building, combined with the use of bronze in the facade, deliver a sophisticated visual narrative, a harmonious blend of modern engineering and timeless elegance.