Robie House

Introduction

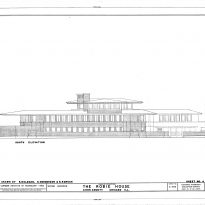

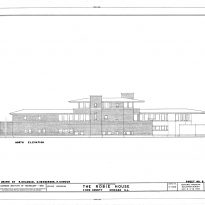

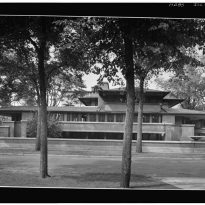

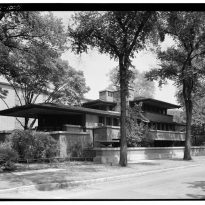

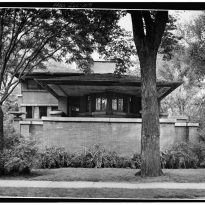

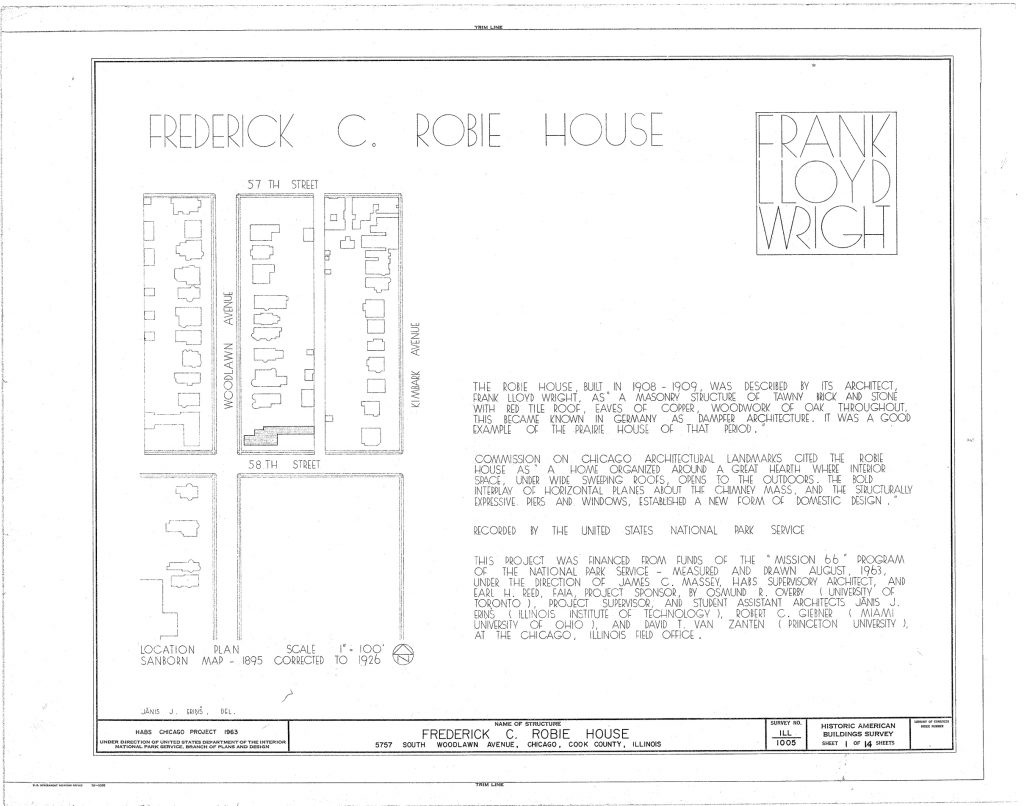

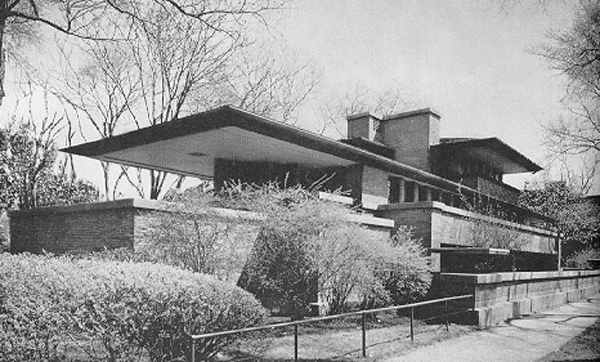

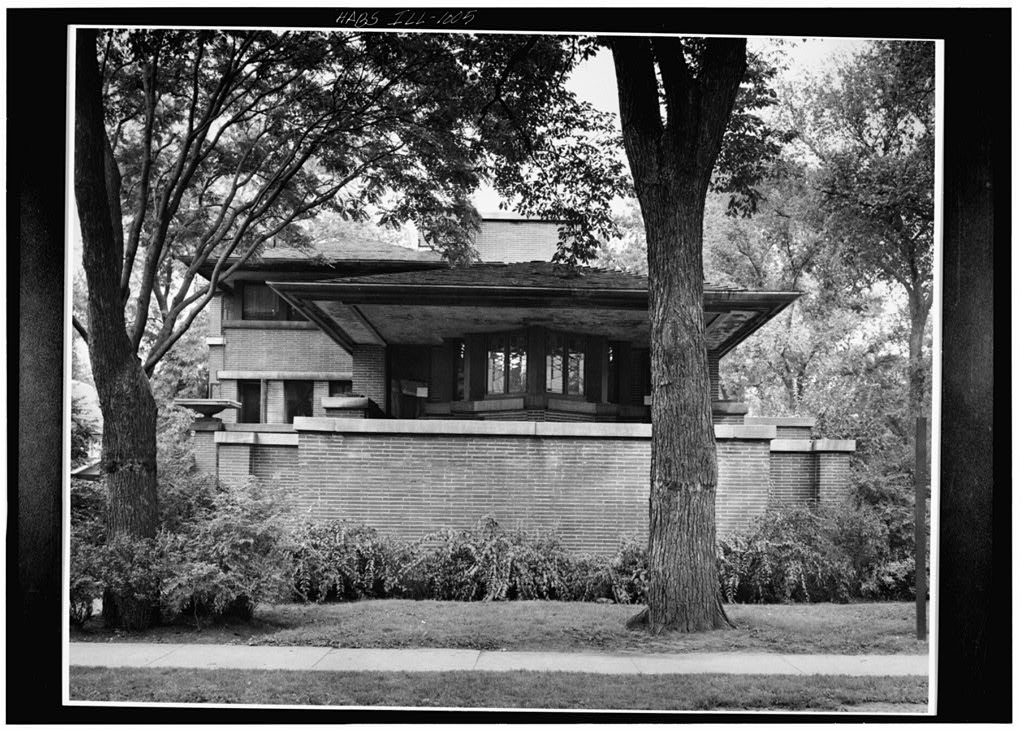

The last and best of the houses in Wright’s prairie era, the Robie House, seems designed for a plain, rather than the narrow corner lot where it is located in Hyde Park, a suburb of Chicago.

At the time it was built, its elongated horizontal profile seemed an exceedingly strange appearance among its conventional and vertical neighbors.

One reason for the huge success of this house lies in the explicit requirements of the customer.

He wanted a house free of enclosed spaces in the form of “blocks” for fire protection and without the decorative elements, such as curtains or rugs, etc. As an engineer, Frederick C. Robie wanted a house that also functioned like a well-oiled machine. That it is situated on an angular plot in large part explains its form, which is very similar to other “Prairie Houses”.

Situation

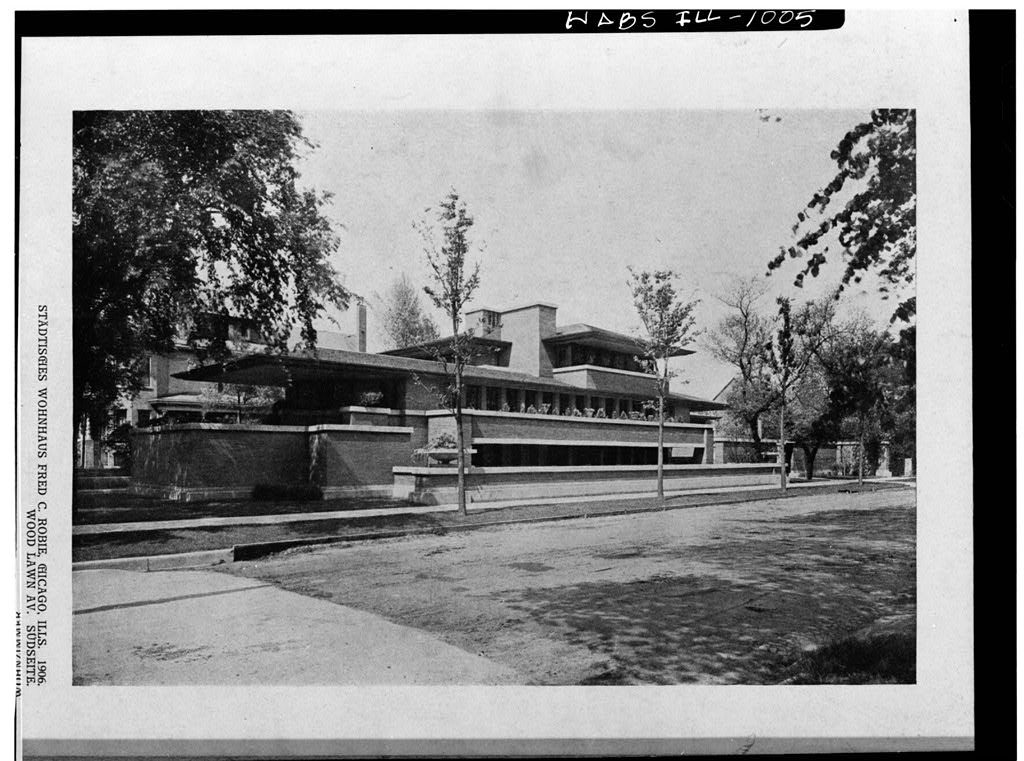

Robie house is located on a corner lot in the neighborhood of Hyde Park, near the University of Chicago. More specifically, at 5757 Woodlawn Avenue, Chicago, Illinois.

Description

Foreign

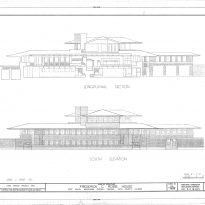

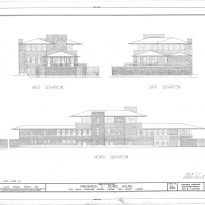

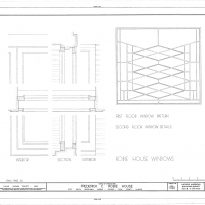

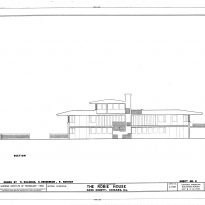

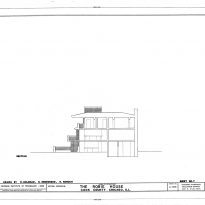

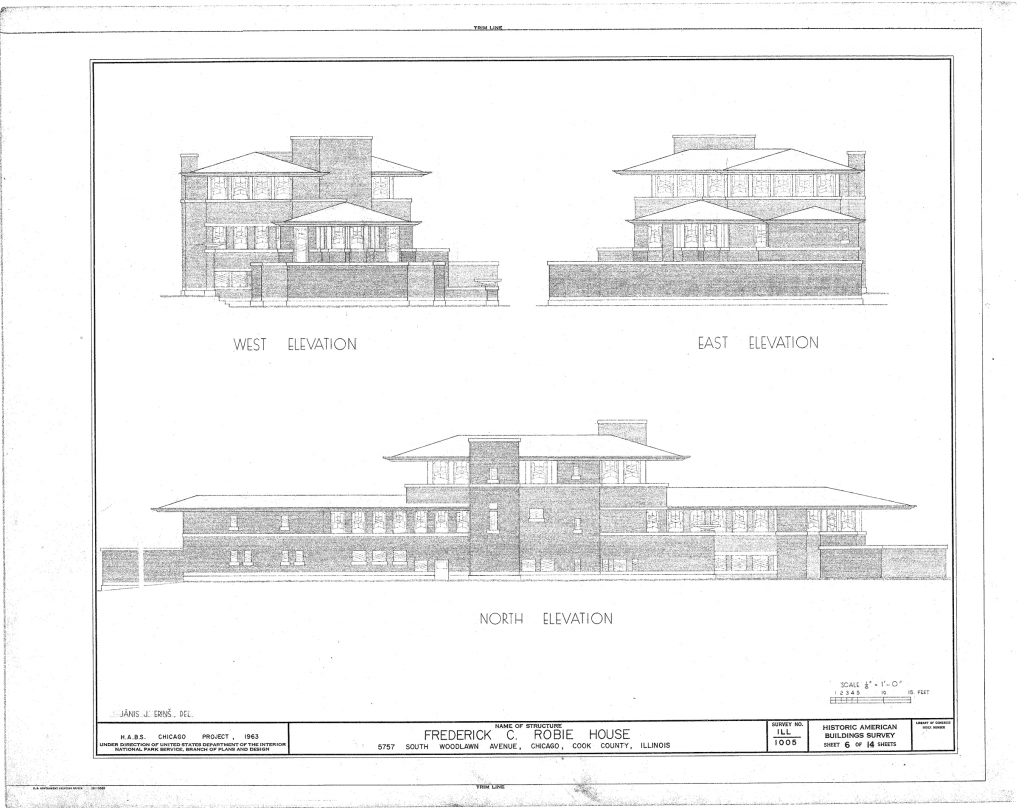

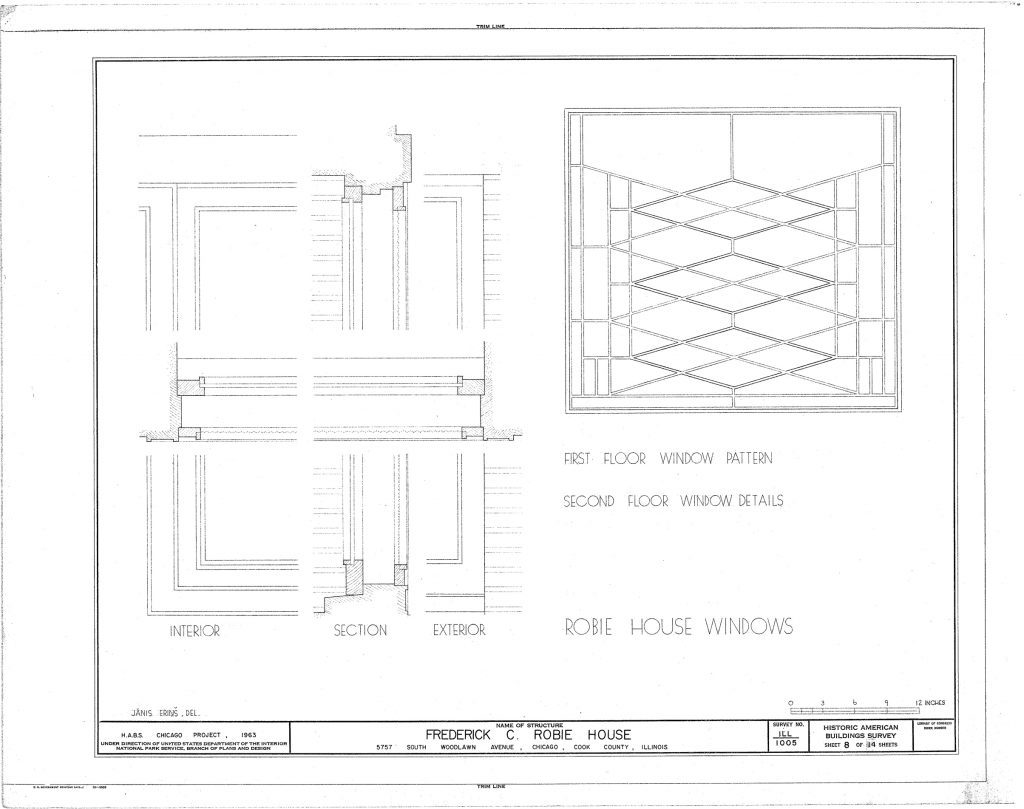

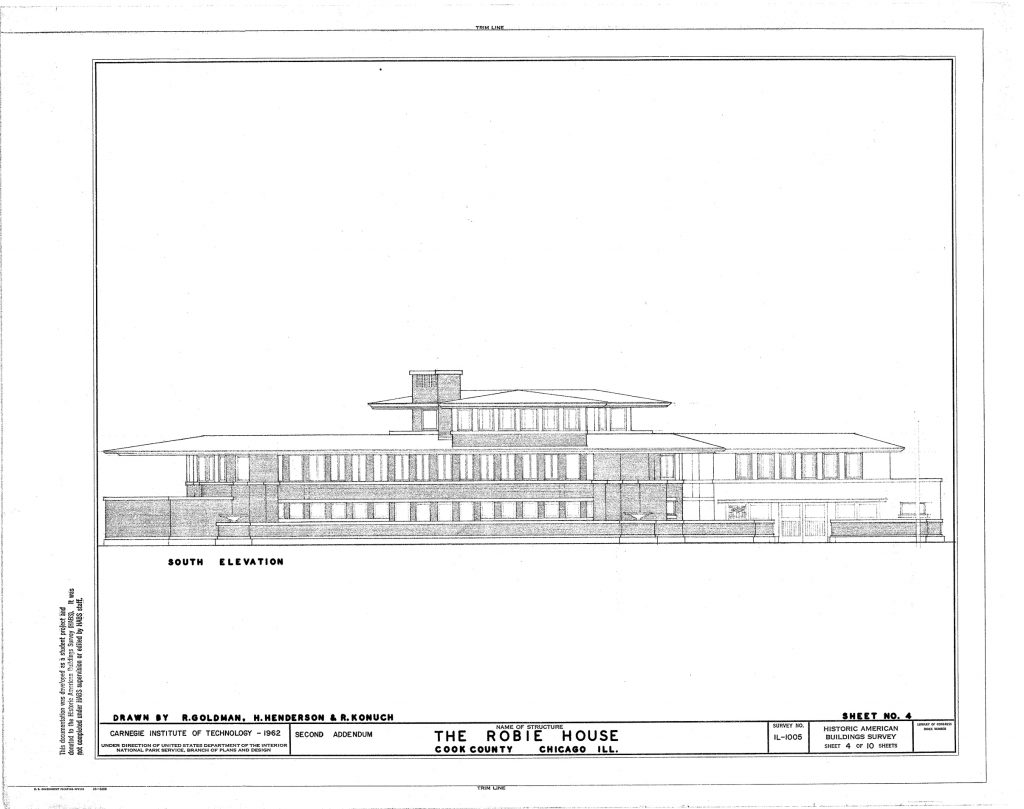

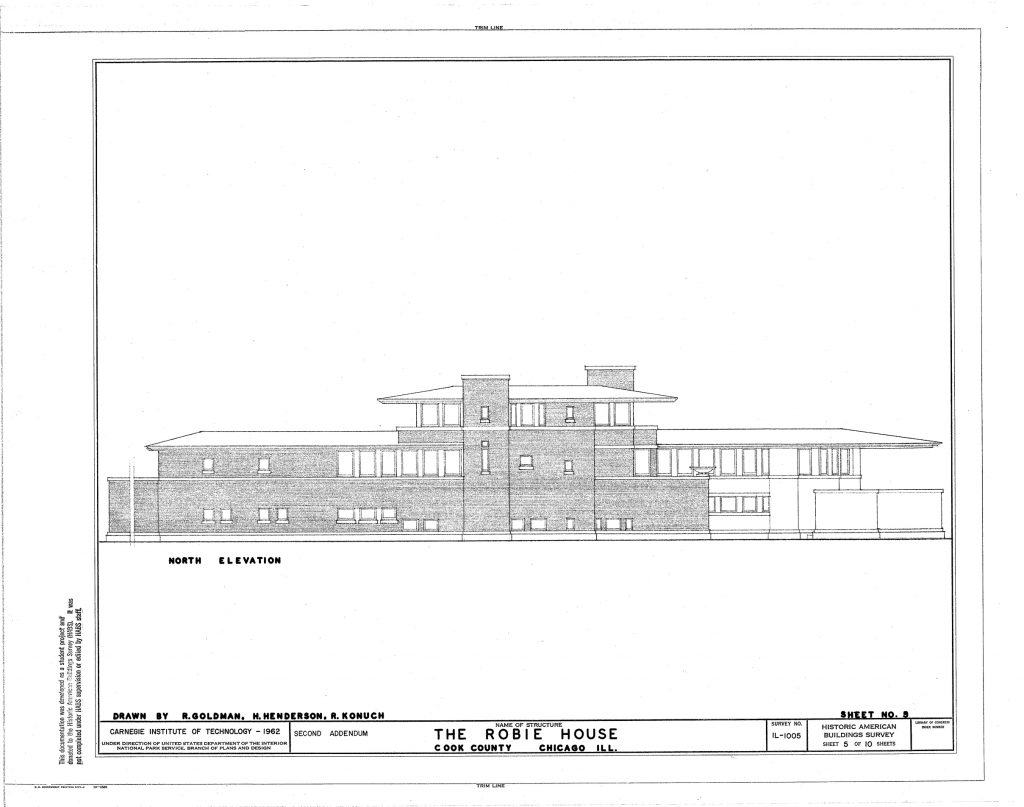

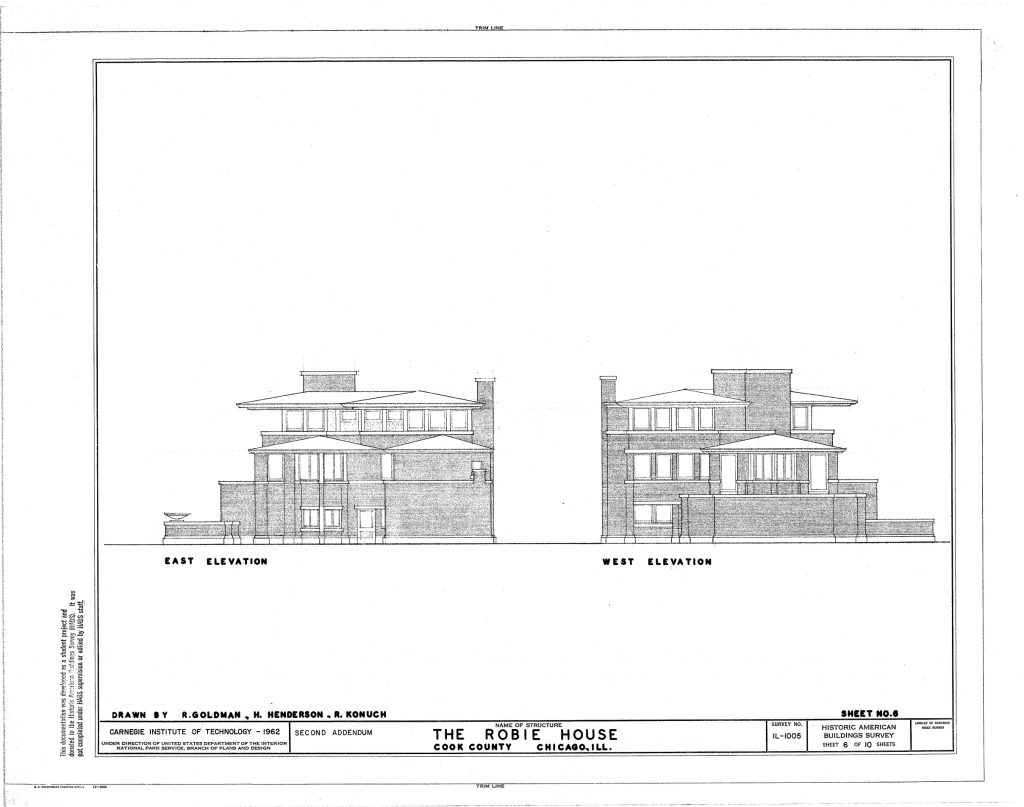

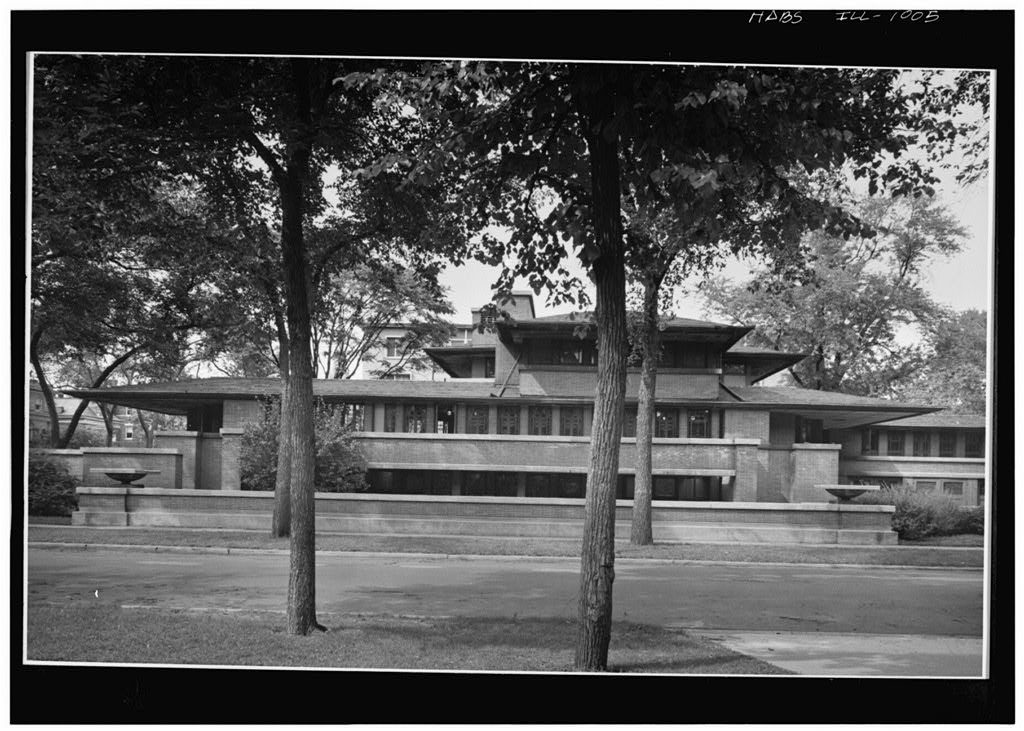

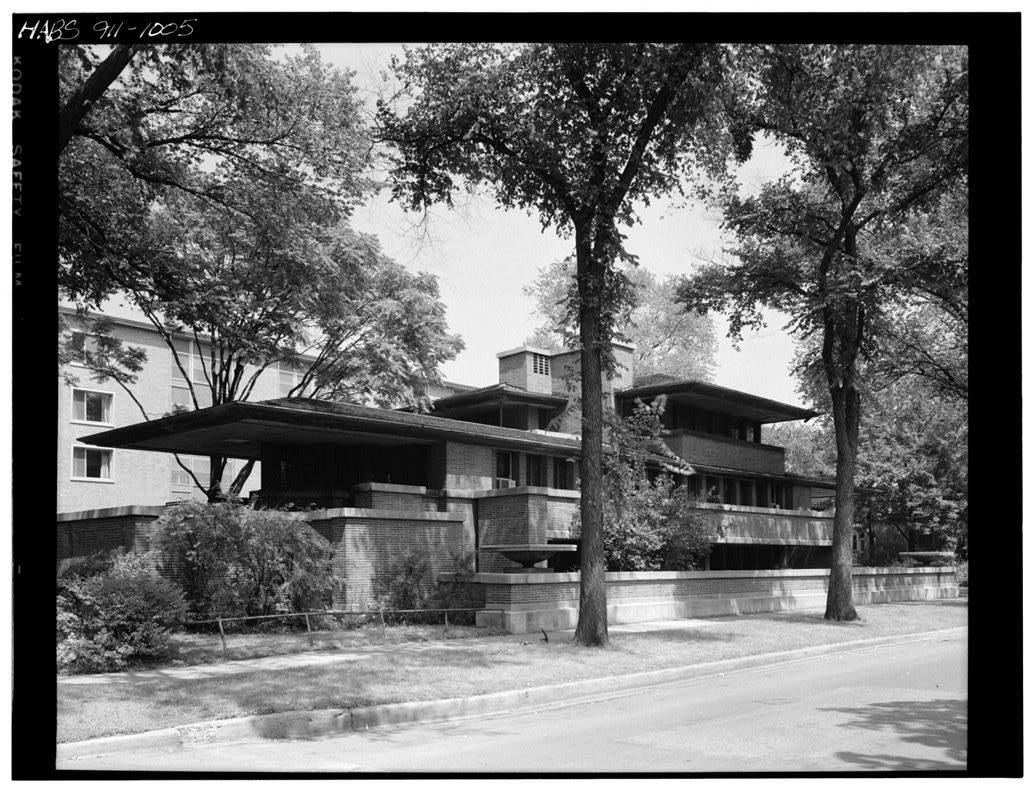

The house has no facade, conventional windows, nor a prinicpal entrance or front door. It occupies almost the entire plot; what little free space left is incorporated in the overall composition with dedcorative walls and gardens. The horizontal feel of the edifice is reinforced by the window sills and stone thresholds, as well as by the thin mortart joints of the brick work.

Compositional method

The method of composition Wright utilized at the time consisted of organizing symmetric forms in assymetric groupings.

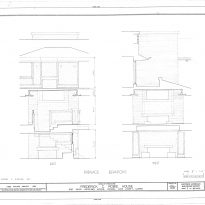

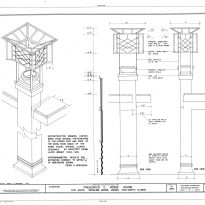

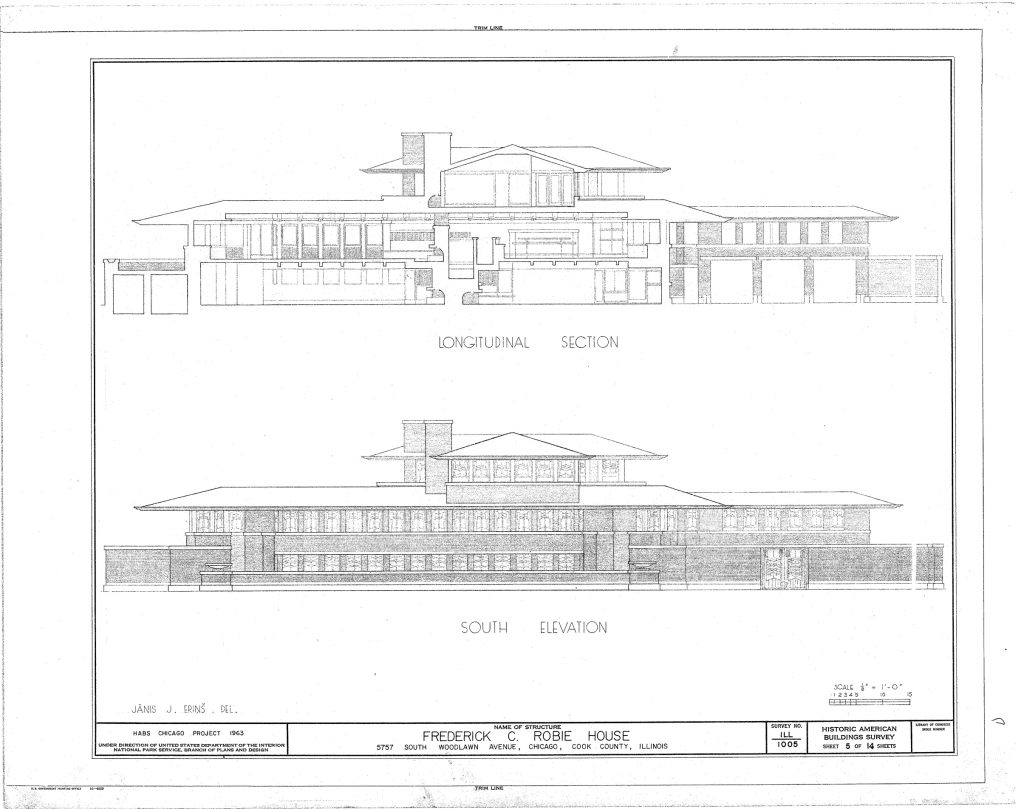

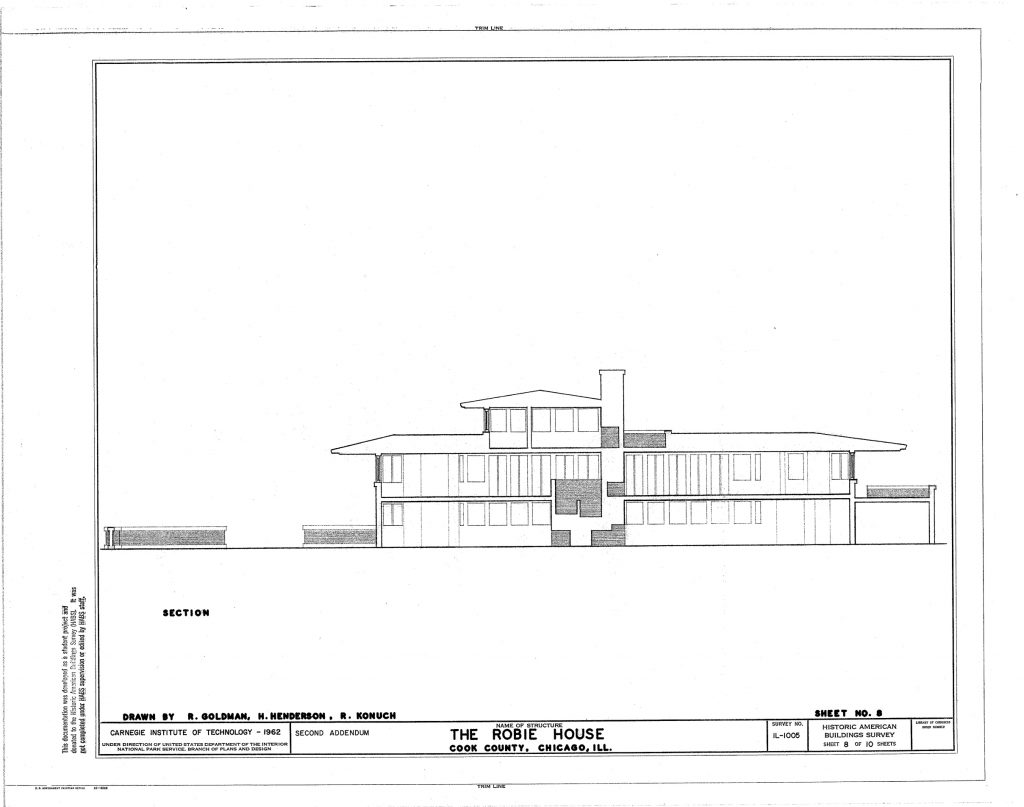

The basis of the composition is a long two-story block, with apparently symmetrical porches, each featuring a sloped roof, at each end. On the first floor of the south facade, which faces the street, there is a row of large doors opening onto a large balcony that projects outward from the house. The balcony provides shade to a series of similar windows on the ground floor.

The symmetry is an illusion, because the elevated terrace of the western end of the house is balanced by the wall of the courtyard to opening to service the eastern end. But it is only one factor in a more complex equation.

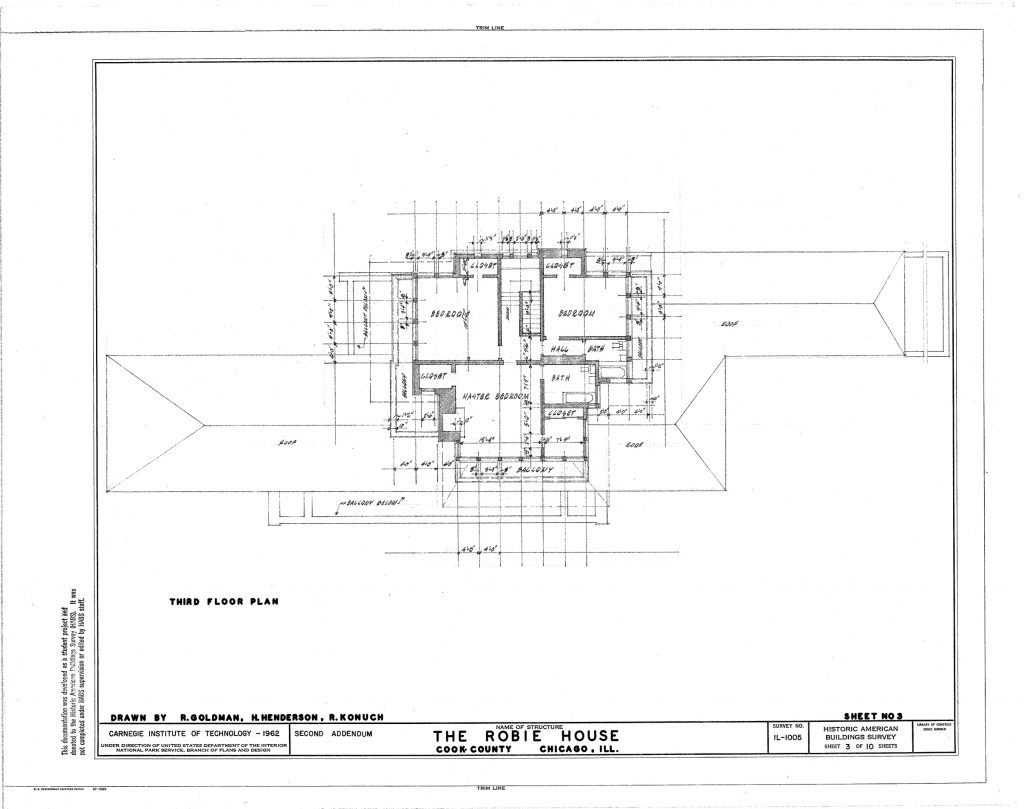

Above the main block, the second floor features bedrooms with windows and covered balconies, creating the conflicting dynamic that sets the entire composition in motion. On one side emerges a large vertical chimney that anchors all the horizontal levels below. Further, at the eastern end of the building, a sloping deck covers a wing dedicated to a 3 car garage and service personnel entrance.

Concept

The house was designed for Frederick C. Robie, a bicycle manufacturer, who did not want a home done in the typical Victorian style. Robie desired a modern floorplan and needed a garage, and a playroom for children. He also required that his home be fire-proof, yet retained an open floor plan free of closed, box-like rooms that would prevent the uniformity of decoration and design.

Spaces

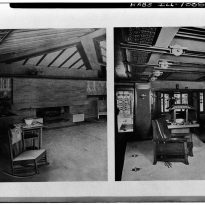

Wright rejected the popular view that indoor spaces should be closed and isolated from each other. In contrast, he designed the house so that the space in each room or hall was open to the other, so that the feeling in the house was one of immense light and space. To differentiate one area from another, Wright resorted to lightweight divisions or different height ceilings, avoiding unnecessary solid room divisions. So Wright was the first to establish the difference between “defined spaces” and “closed spaces”.

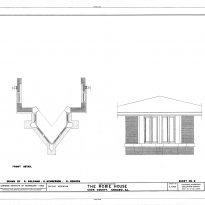

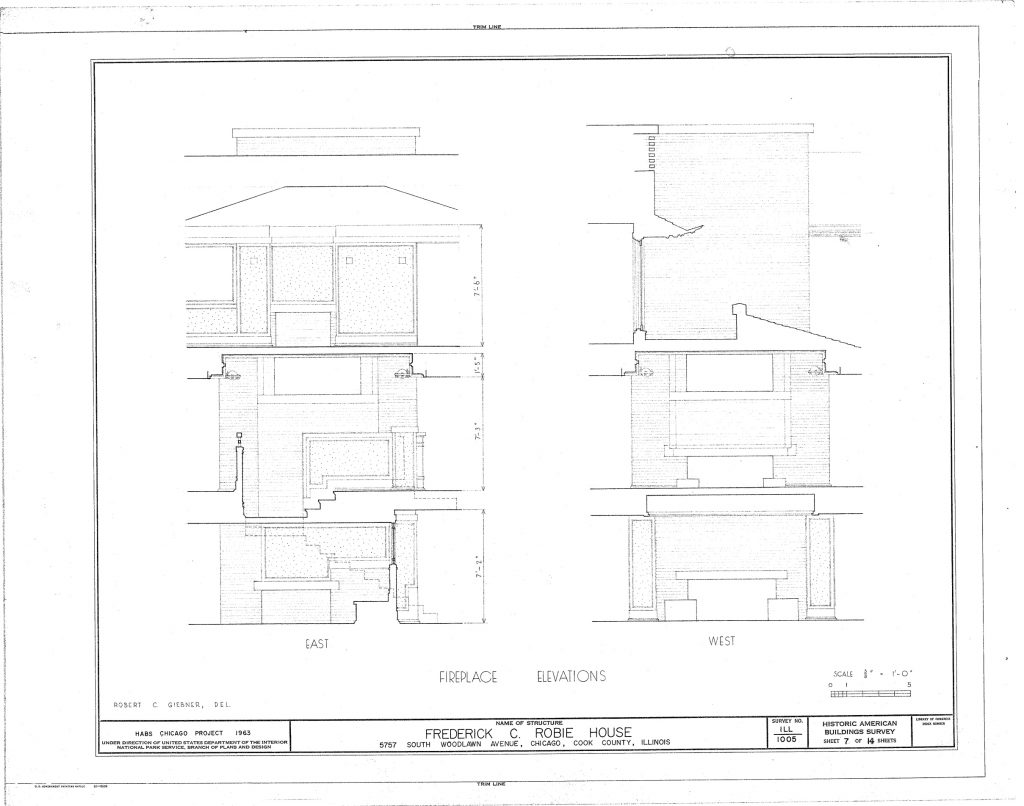

The significance of Wright design of the Robie House is that he neglected the conventional ideation of a house as a box containing smaller “boxes” for rooms. By contrast, the interior space is fluid and transparent, allowing the entry of light without obstructing the view. This “explosion of the box” produces the effect of walls unfolding to reveal large, vast spaces. The floor composition is based on two adjacent horizontal bars that are mixed in a central space, anchored by the vertical column of the fireplace, around which the rooms are arranged and interconnected.

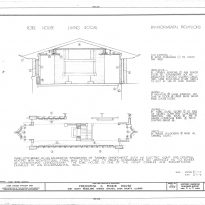

The design draws on the wide terraces and eaves to achieve a solid and strong, yet lightweight and hollow appearance. This concept of eaves and large terraces was used later by Wright in the Fallingwater House.

The house is divided into two wings, keeping the public areas toward the street and the service areas near the innermost sections of the house.

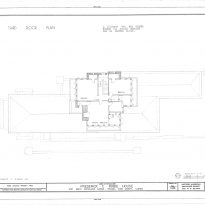

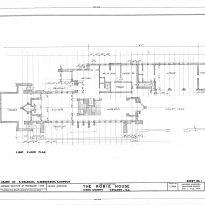

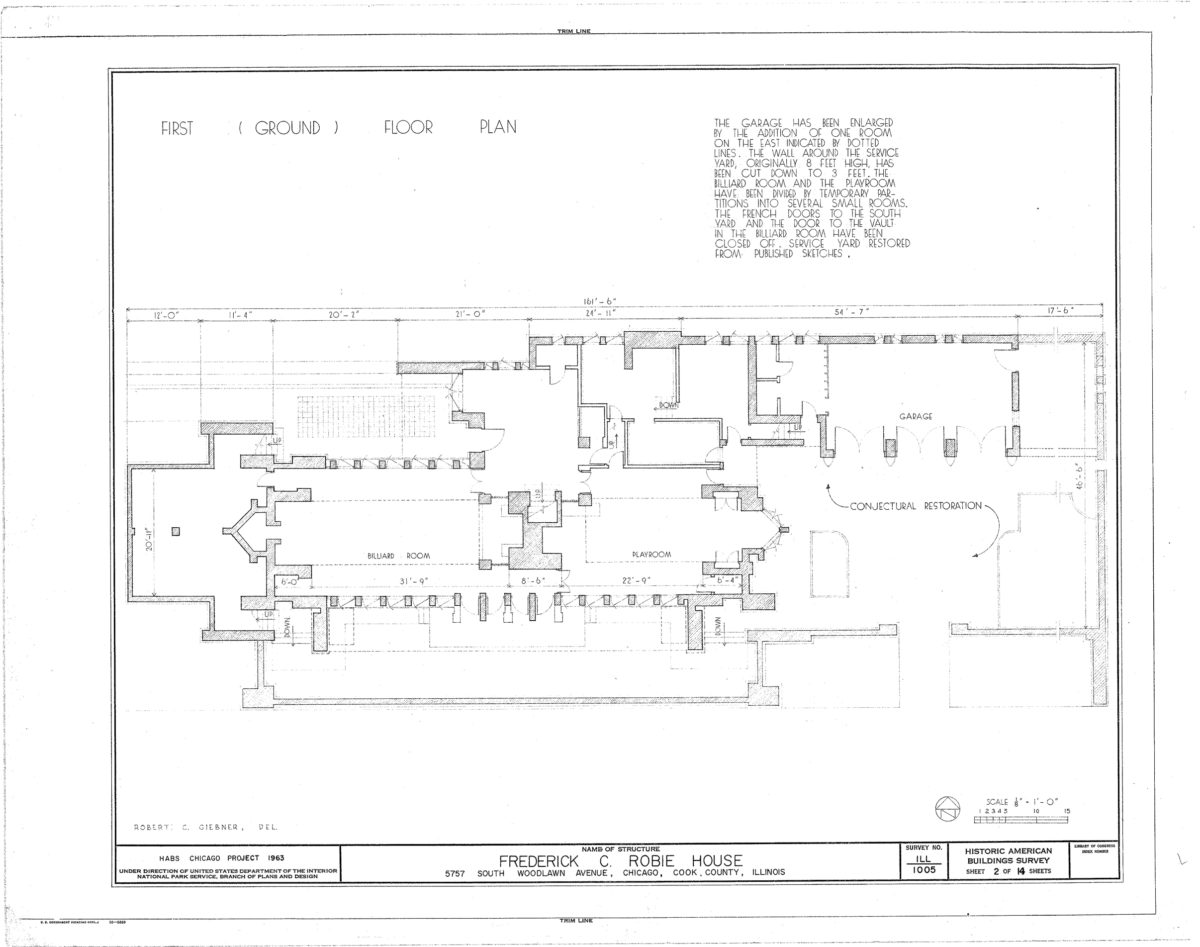

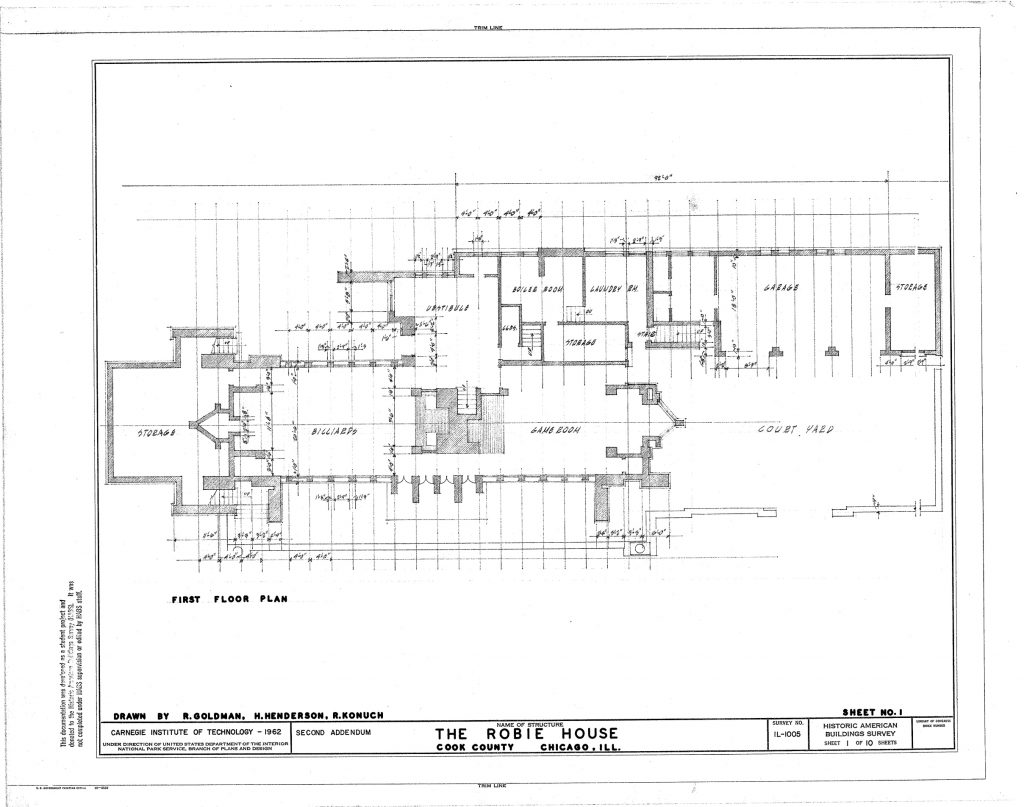

Ground Floor

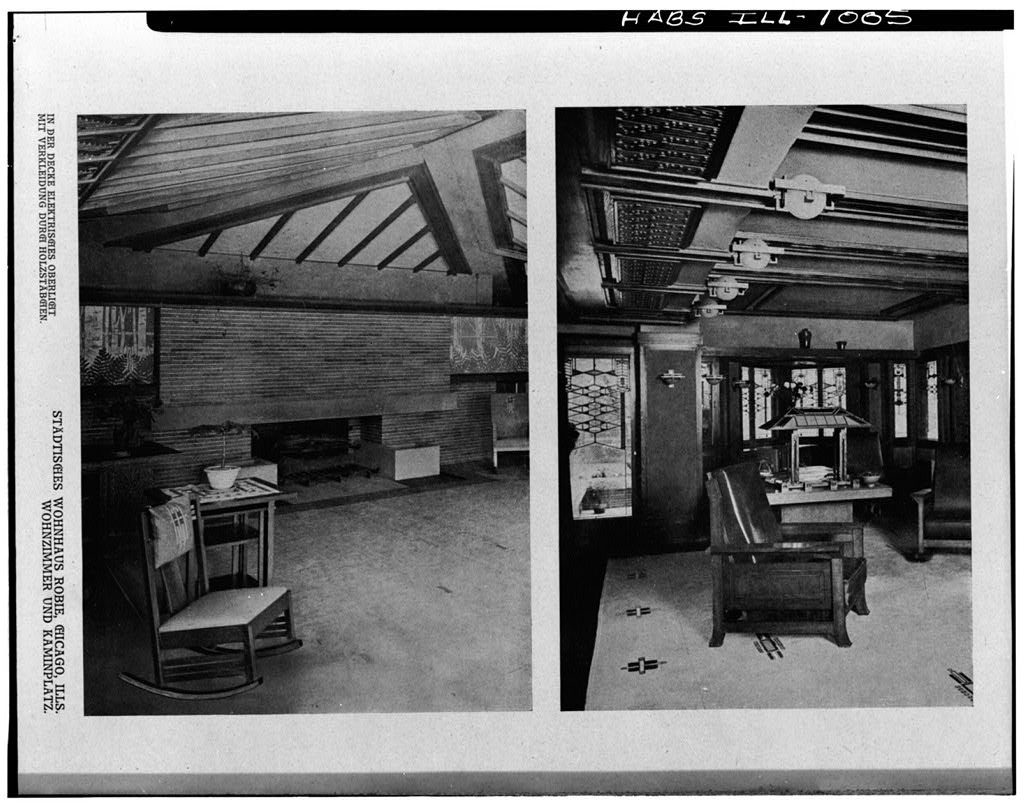

A game room and billiard room make up this level, separated by a fireplace. In both spaces, Wright chose to showcase the system of structural beams in the ceiling, to give a greater sense of altitude to the rooms.

This level also houses the utility equipment, laundry, pantry space, and a 3-car garage. Access to the house is at this level, with access to the main living area via stairs.

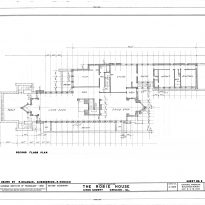

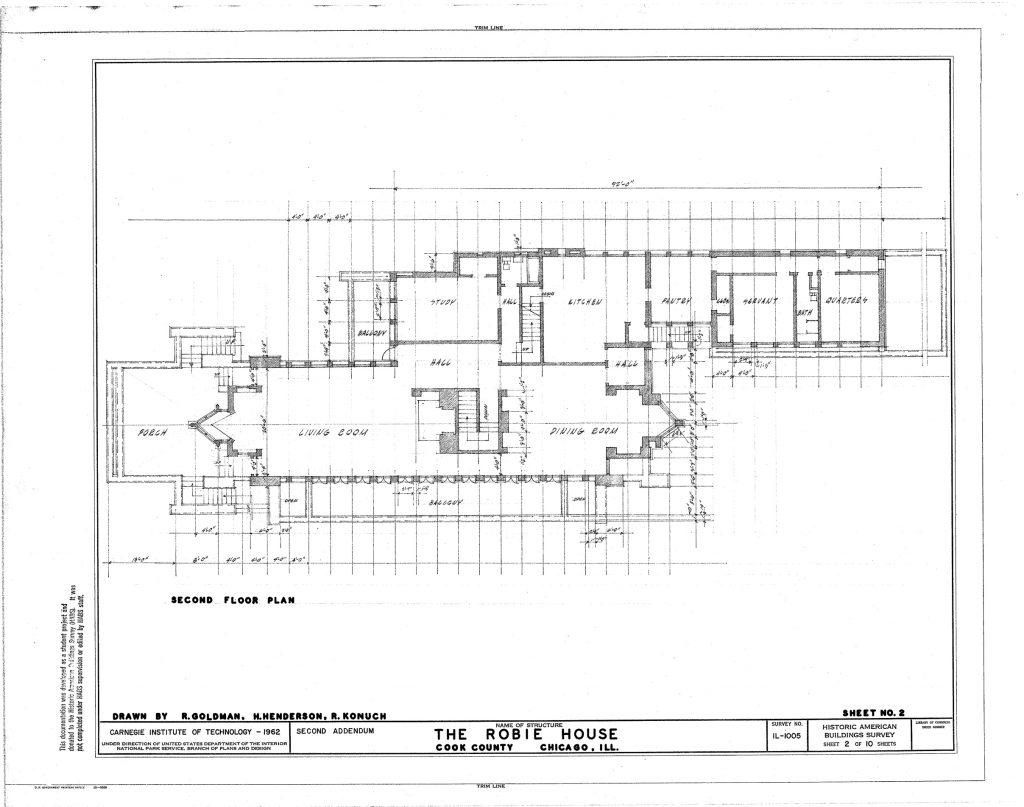

Second level

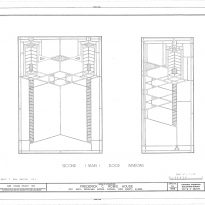

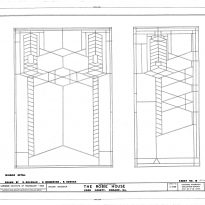

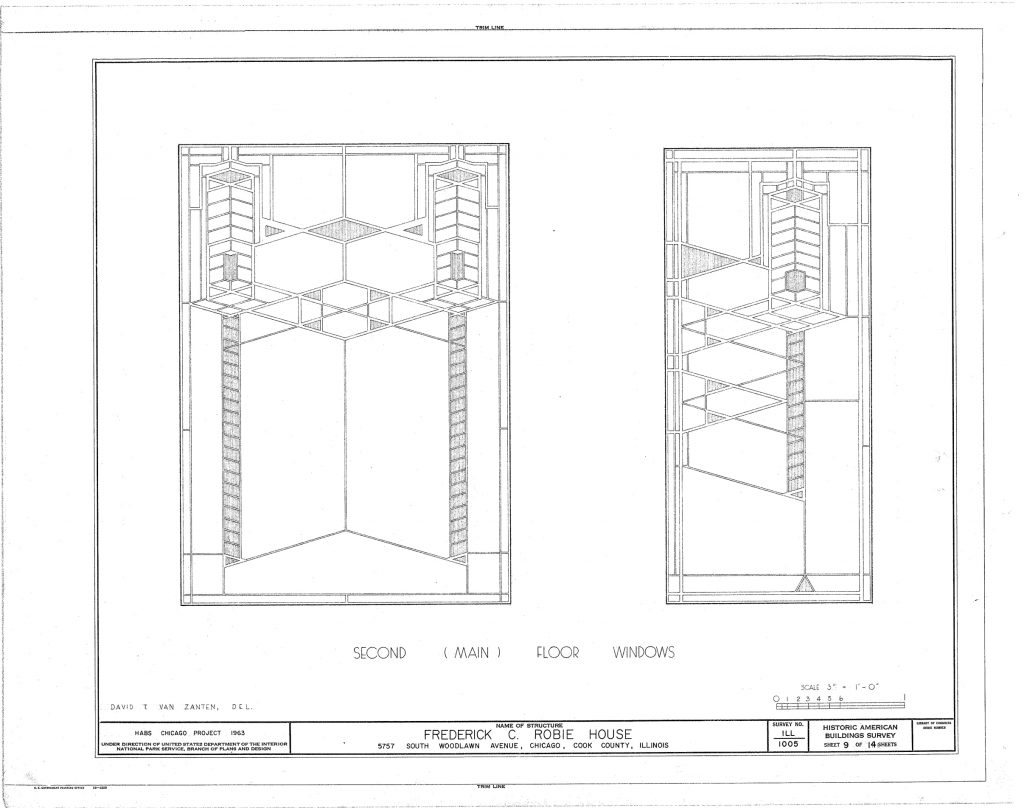

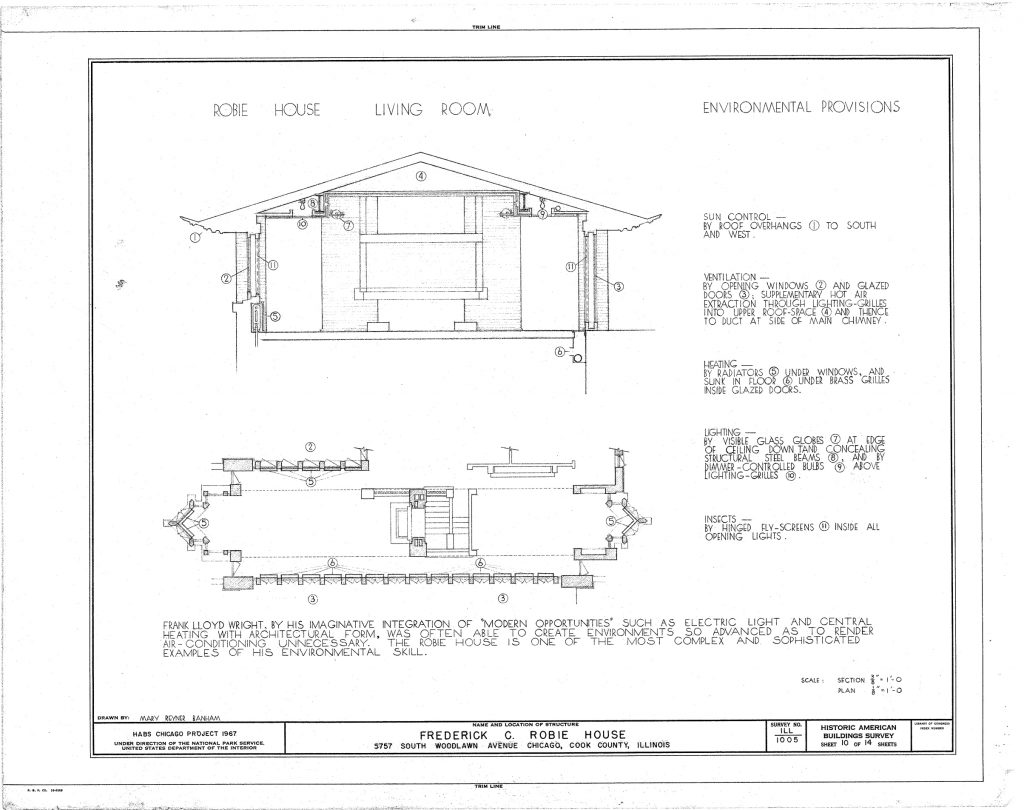

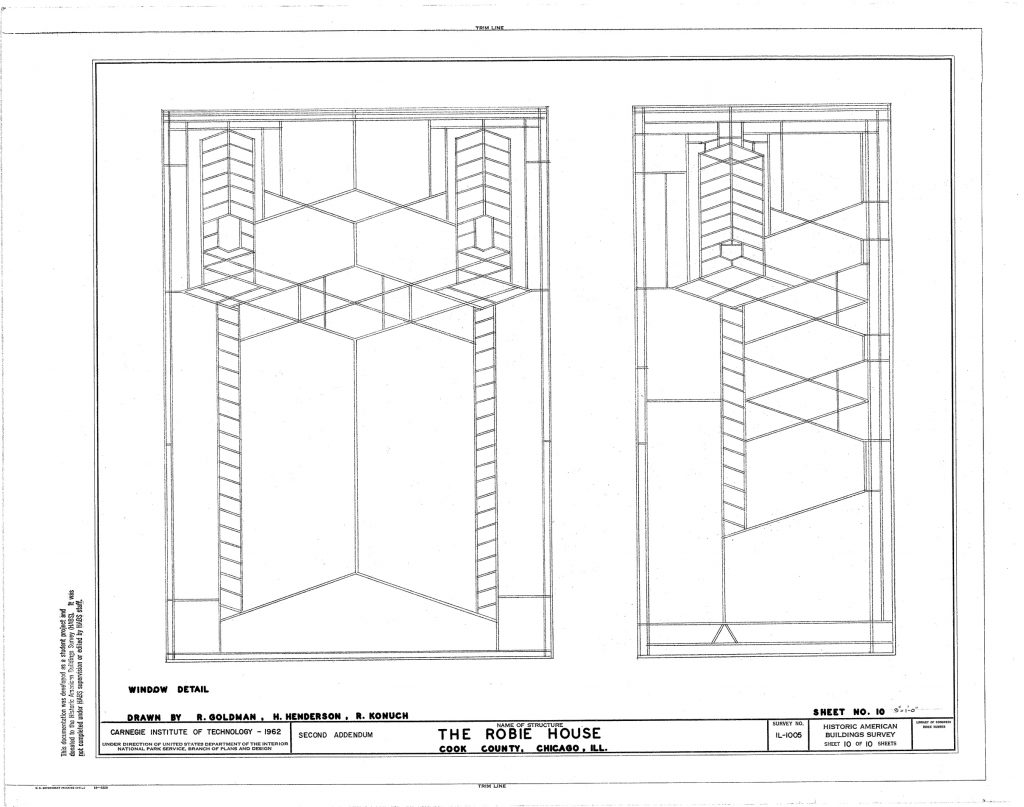

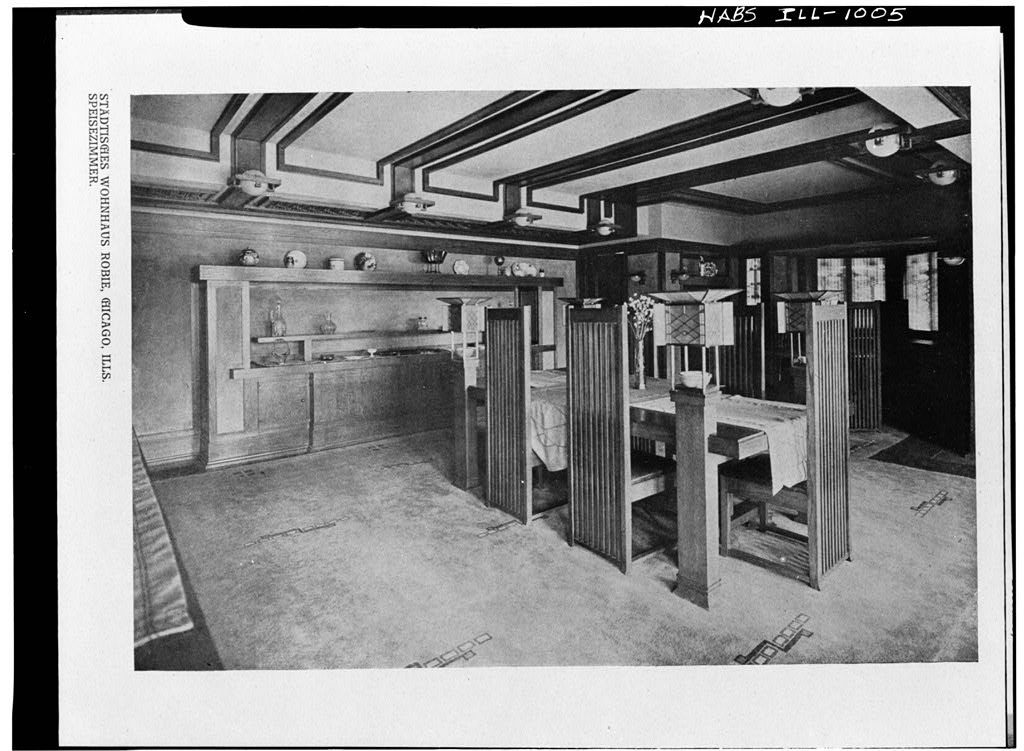

The second floor of the house is composed of the kitchen and the servants’ quarters. But undoubtedly the most interesting rooms are the living and dining rooms, separated by the fireplace, but visually connected. These rooms feature a wide space without walls that obstruct the visual from the outside, which recalls the vast spread of the prairie and at the same time allows the diffusion of light from the inside. However, the eaves are designed such that they protect the inhabitants privacy from prying eyes in the street.

Here, climb the central staircase, which leads to one of the most famous domestic interiors of the twentieth century: a large loft, long and low, as the living room of a boat, gaily lit by skylights opening to the noon sun.

The space is divided into two areas, the living and dining areas, which symbolize the most familiar elements of living and roots the house to the earth.

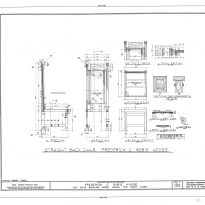

The chimney, which has a massive presence in the central space, is not an obstruction since it is possible to maintain the continuity of the roof structure around a central opening. In turn, the ceiling is divided into panels, each equipped with two types of electric lighting: glass globes on each side of the higher central zone and bulbs hidden behind racks of wood, in the lower side zones.

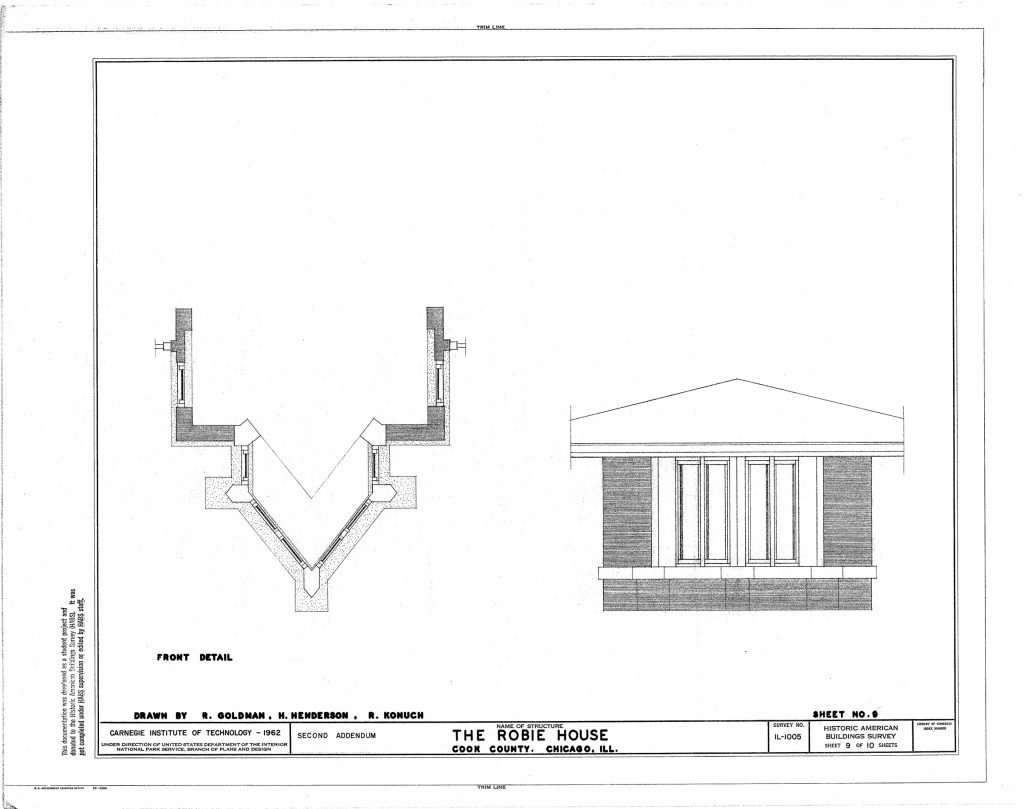

On both ends of this space the two long galleries form triangular areas that are more intimate, for relaxing or eating. These spaces are barely visible from the outside due to the intense shade thrown by the extensive flying eaves. These decks could not be built in wood, in fact, they are held by two hidden steel beams that extend the length of the main block.

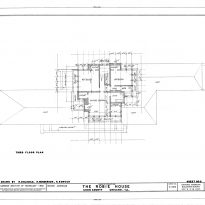

Third level

The bedrooms are at this level, overlooking the house in a sort of tower-style.

Materials

The house is clad in Roman brick and limestone.

To achieve those enormous eaves, Wright pioneered the use of steel in the structure of the house by using two main beams that run lengthwise along the same axis as the fireplace. Wright chose to cover the sides of the beams, leaving a high ceiling area in the center, which has the effect of creating the illusion of vast vertical space.

The use of wood strips arranged perpendicularly to the direction of the room and rhythmically placed lights reduce the feeling of a long narrow space. Two angled rooms at the ends further reinforce the idea that space is extended outward.

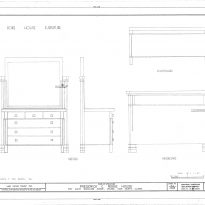

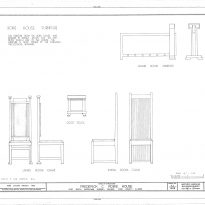

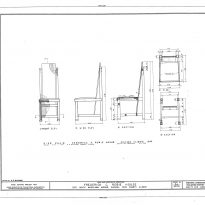

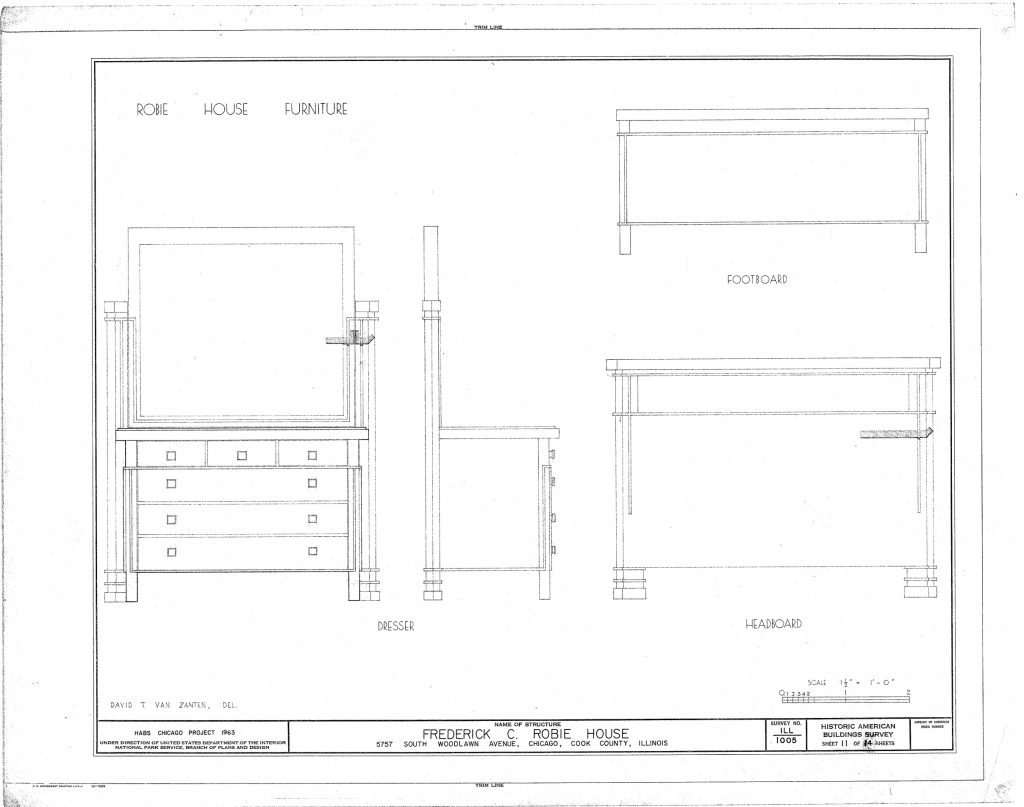

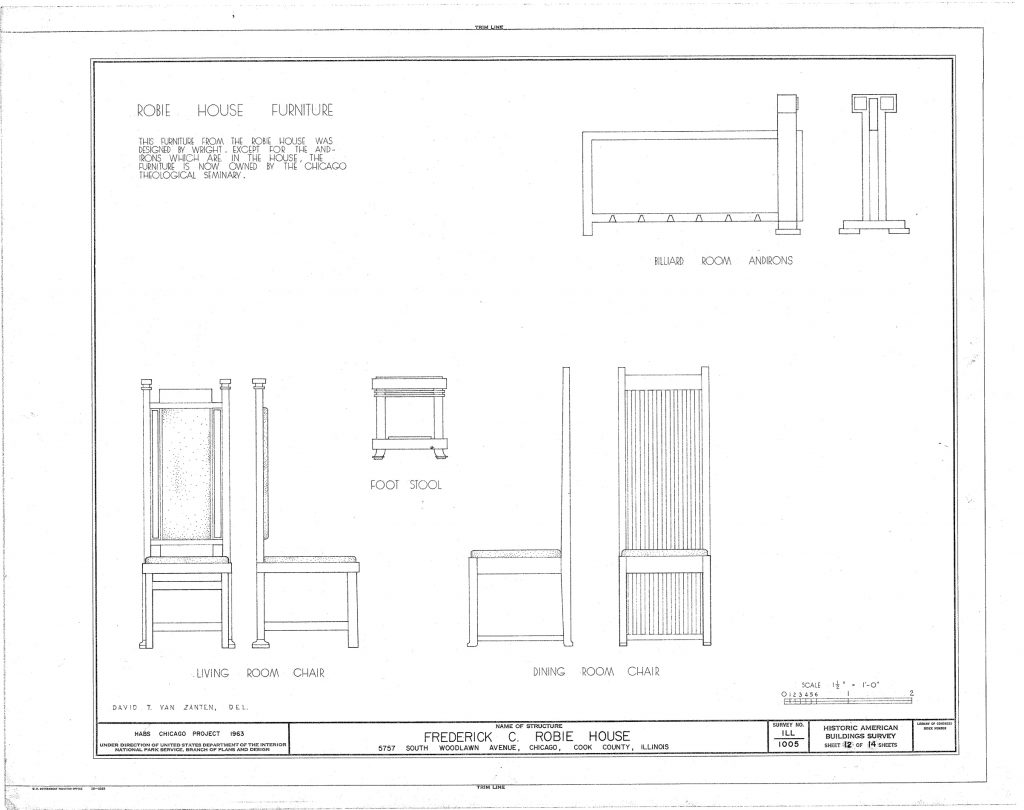

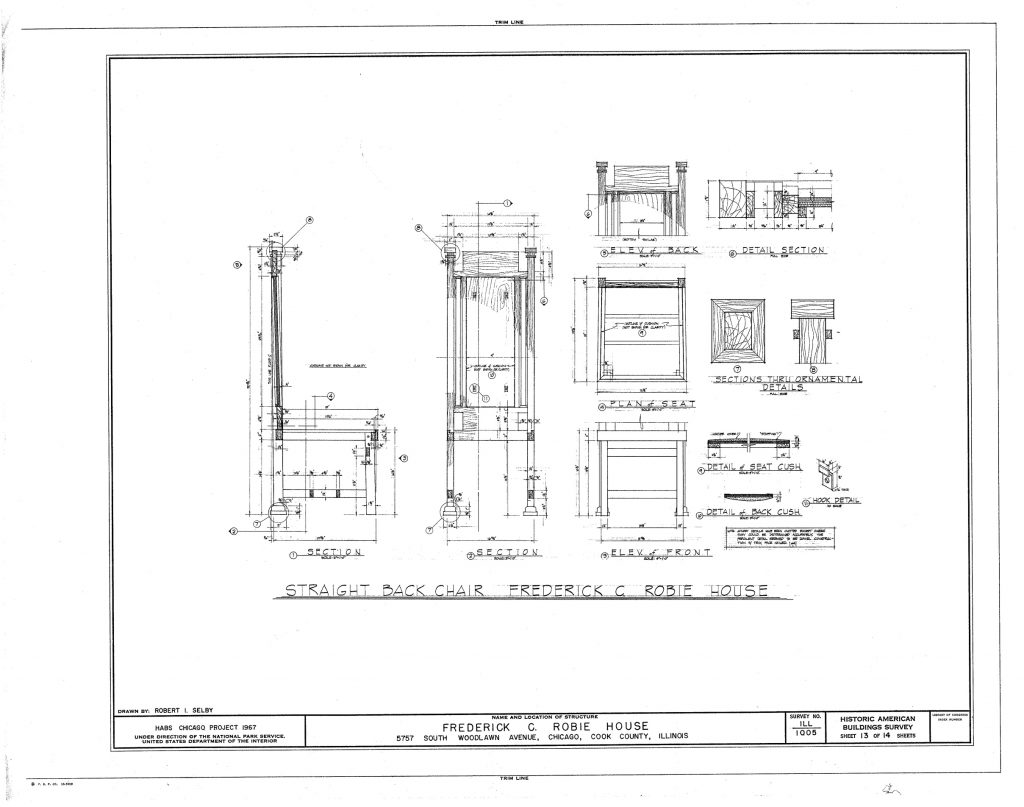

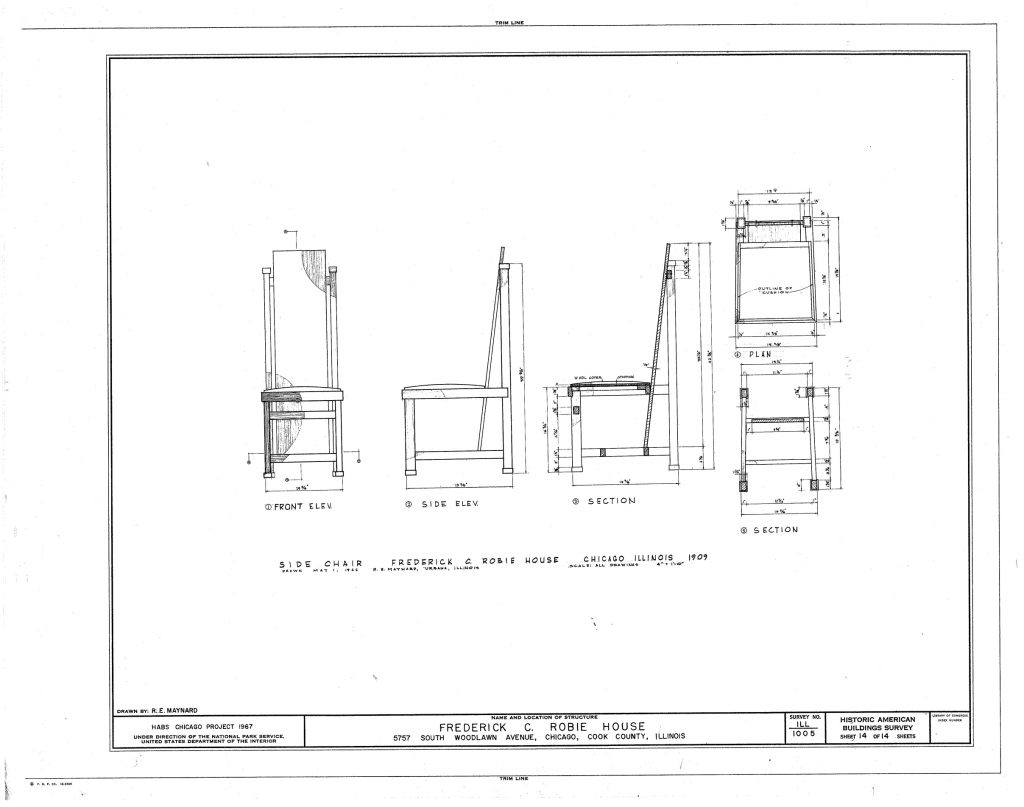

Furniture

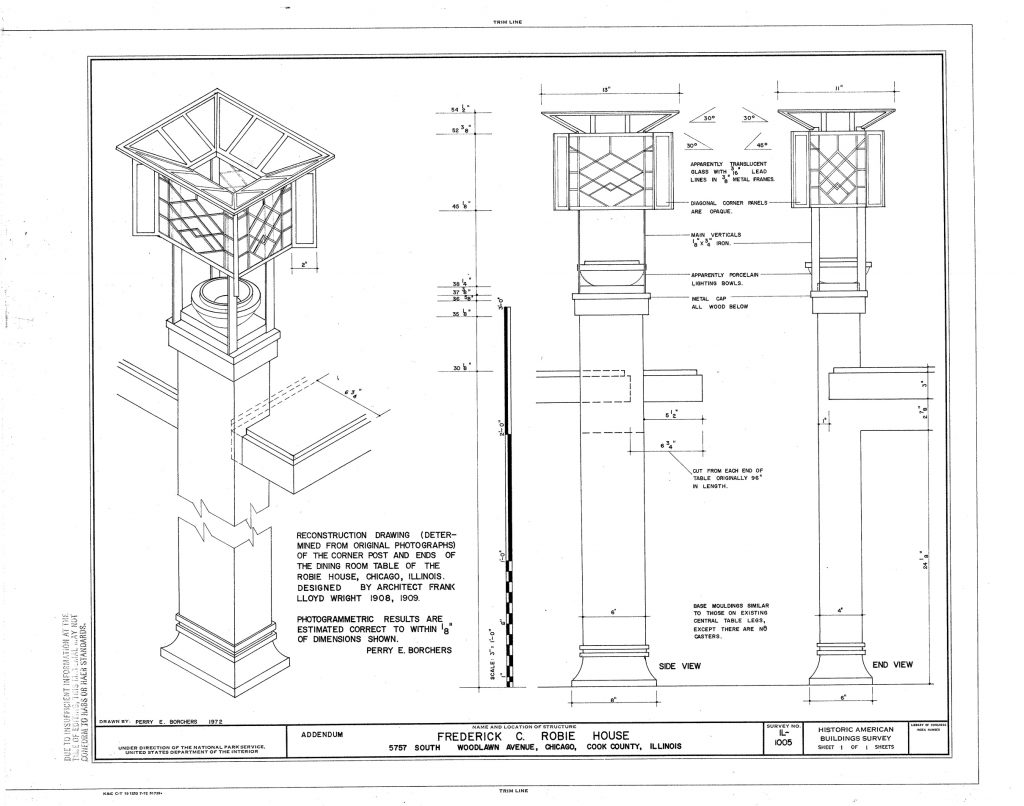

All the furniture was designed by Wright; the dining table and chairs housed in the dining area were exceedingly popular.

The table rests on four columns at each corner with lanterns and colored glass containers for floral arrangements. This design stemmed from an obvious issue: the chandeliers and floral centerpieces that are usually placed in the center of the table are a visual barrier between the hosts and guests. Here, however, the decor and lighting are located on the corners, leaving the center of the table completely free.

Videos