Hanna House / Beehive House

Introduction

Wright built the so-called “beehive house” for Jean and Paul R. Hanna, a couple of professors who intellectually aligned with the views of John Dewey, one of the most staunch American critics of the city and 20th-century society.

The social ideas of the time, shared by Wright during his Usonian period, created an ideal atmosphere for the relationship between him and the clients, and allowed them to endure a challenging construction process.

In a letter Wright sent together with the first sketches for the house in April 1936, he conveyed his hope of abandoning the box shape and right angles to design following the geometry of bees: “I hope the unusual shape of the rooms doesn’t bother you because they should actually be quieter than square ones and you have little irregularity… While the project is spacious and expands on its own, it is not very extravagant. I hope you both like it as much as I do once you get used to its unusual proportions.”

Wright’s Usonian Period

Usonian is a neologism taken from Samuel Butler that Wright uses when referring to an ideal, utopian United States (USA) that his work should help build. Usonian would be a world of liberated men, meaning: “in accordance with their nature and vocation.”

The term was used in the late twenties and early thirties, during the economic recession when Wright began to design architecture made from cheaper, simpler materials, and thus an architecture capable of contributing to social transformation.

Location

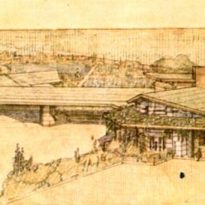

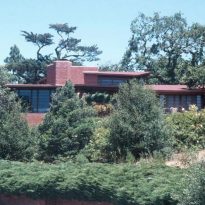

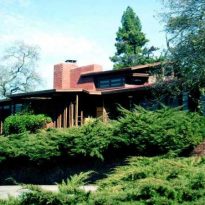

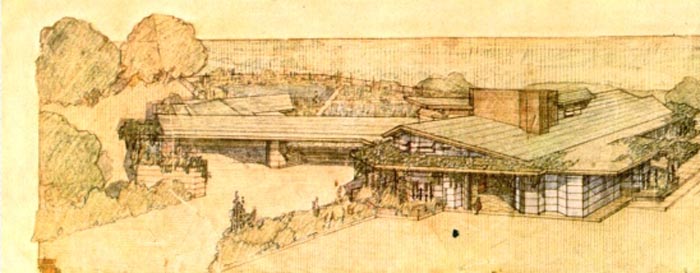

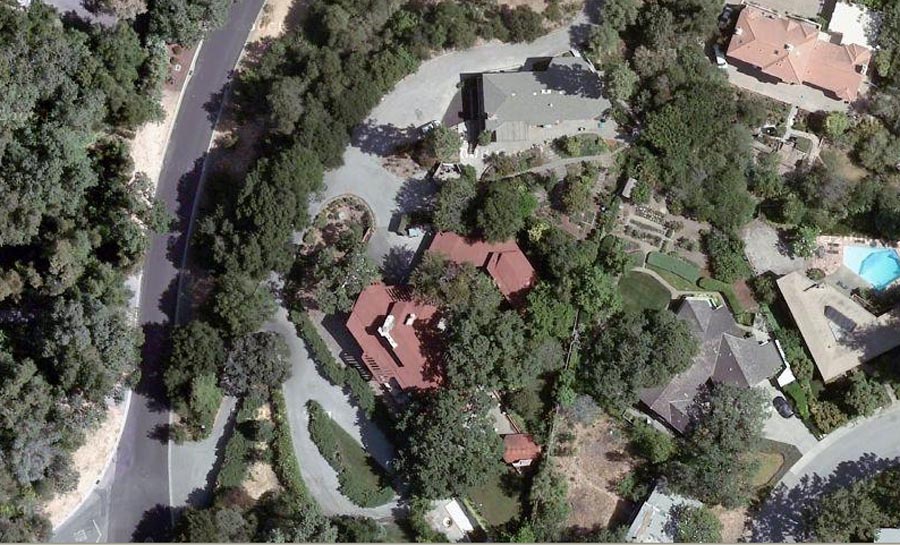

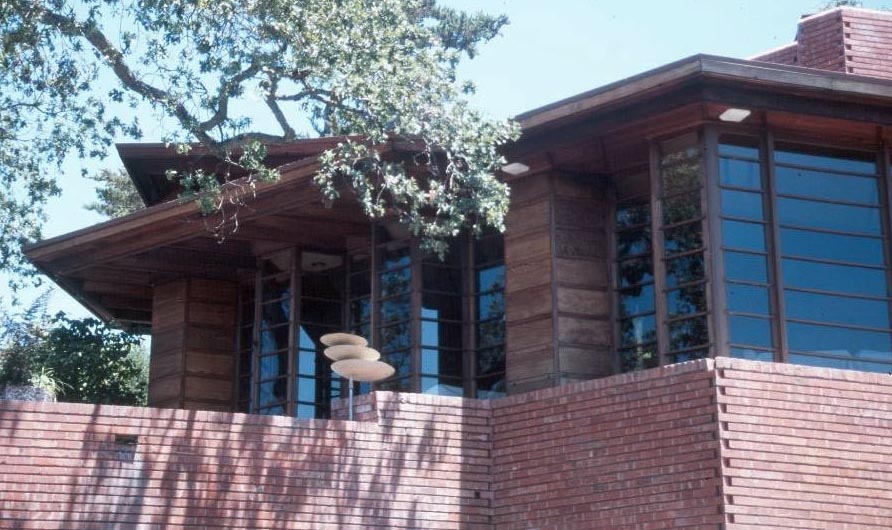

The house is located on the slope of a hill with a slight incline towards the west, and is articulated around three ancient oaks that were found on the property.

It was built on the Stanford University campus, at 737 French Road, Palo Alto, California, USA.

Concept

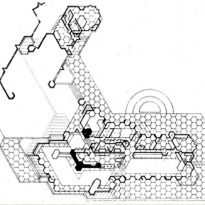

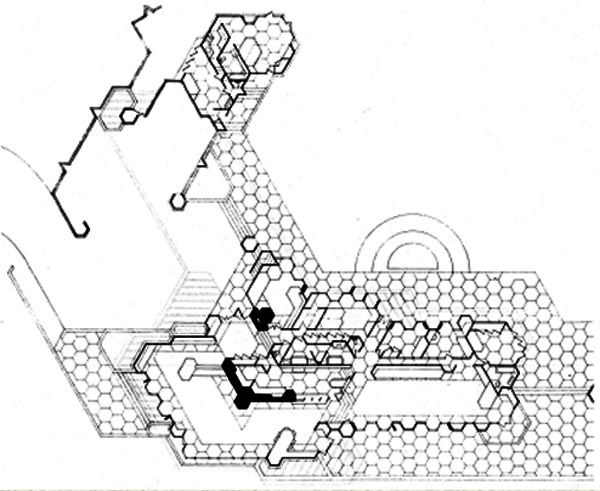

In his continuous search for a more flexible floor plan, which would result in an equally more flexible interior space, Wright adopted the hexagon and the hexagonal grid, which he preferred over the square or rectangle.

Wright had previously used hexagonal grids as the basis for the elaboration of some projects like the Cudney House in San Marcos (1928), the San Marcos Hotel project, and the Steel Cathedral in New York (1936). But none of those projects achieved the complexity and richness of possibilities that the Hanna House did.

Description

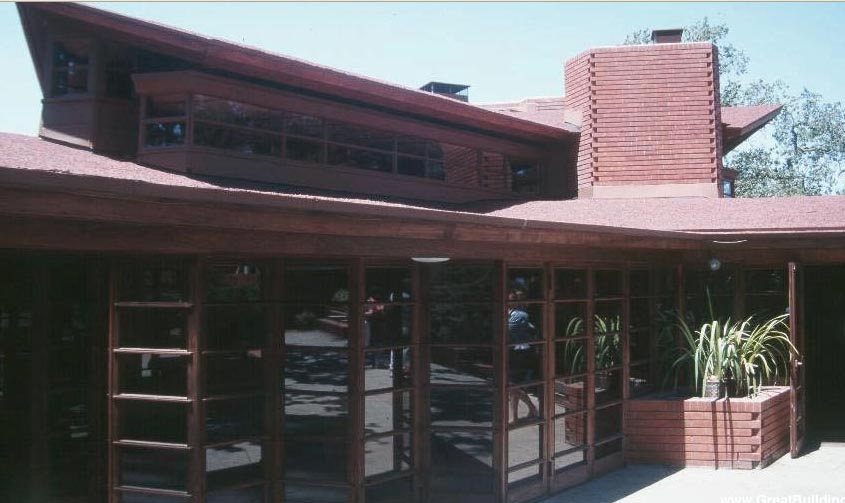

From the outset, one can get the feeling of a continuous envelope, which is achieved thanks to the facade’s foldings, following the laws of the hexagonal grid, and the wide overhangs that project towards the visitor, unifying the garage roof with the access itself. As in almost any of Wright‘s homes, the chimney, which in this particular project is, of course, hexagonal, acts as a central core.

However, the house itself is not a hexagon but has a floor plan with larger angles, 120 degrees, than the usual right angles. As it was a prototype, the project required a large number of drawings and sketches to develop plans that were easily understandable to the builder and workers.

Interior Spaces

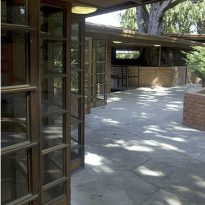

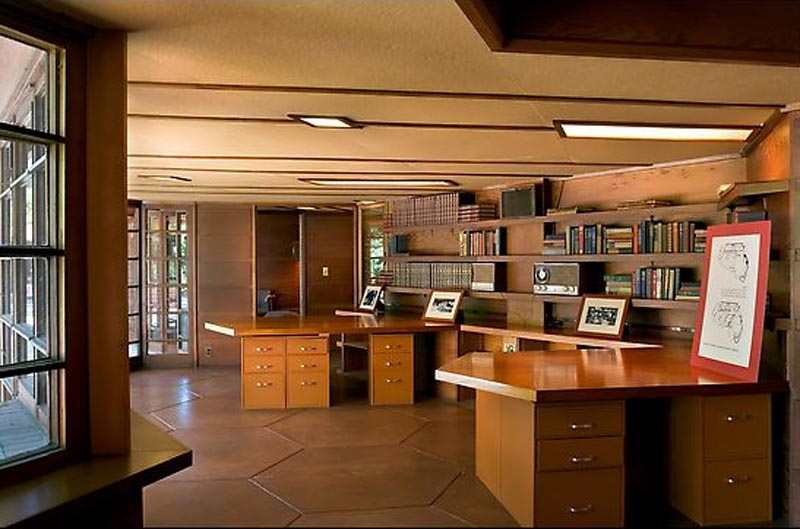

The access happens from the eastern end, connecting the garage and a first courtyard, and serving as an exterior anteroom before joining the main hall of the house, which features double-height ceilings and opens to two main areas: the living room, facing west, and the rooms and study looking east and southeast.

The kitchen, which Wright labeled as a laboratory in his floorplans, is found in the central core, right behind the chimney, along with the bathrooms, which feature a particularly high ceiling that creates the necessary space to house the installations and clerestory windows, typical of other projects from the Usonian period.

Clerestory Windows

These lanterns are an interesting invention that combines two elements: the upper one allows the kitchen and bathrooms to ventilate, and the lower one allows morning and midday light to pass.

The rooms are grouped around the contours of the house, forming spaces that slowly reveal themselves.

Exterior

Guest House

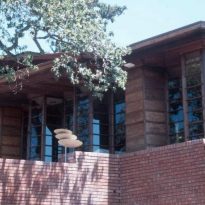

The guest house is located in the back and slightly higher up the hill. This is where the full-time caretaker of the house lives nowadays. It has the same floor-to-ceiling segmented windows as the main house.

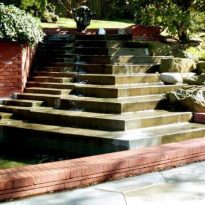

Waterfall

Located at the rear of the main house, it reflects the hexagonal pattern in which the entire site has been designed.

Materials

Although Wright refers to this house using the term “wooden house”, in reality, it has been constructed using a combination of red bricks and wood, both inside and out.

The entrance porch uses flat red San Jose brick, as does the chimney that forms the central core of the house. The horizontal joints of the brick are about an inch tall and finished with mortar, while the vertical joints are leveled. The exterior of the house is a combination of these bricks and wood.

The external roof is made of concrete, and several hexagonal modules have been built on top of it to house plants and protect the old oaks on the property.

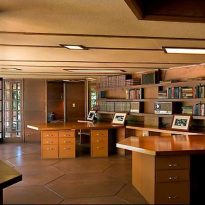

As in the early Usonian houses, Wright used wooden walls inside, made out of boards and battens. The large boards were secured with screws to the structural blocks, and the surfaces were defined by a sequence of horizontally placed boards and their intermediate joints.

The absence of internal masonry walls allows more flexibility in case the spaces needed to be modified in the future.

Wright used softer Cypress wood for the horizontal boards and hardwood for the frames.

The horizontal modulation established in the walls is also used to define the position of the window crosspieces and balconies, as well as the appearance of shelves on the interior walls.

The floor is covered with a thick carpet that adds a natural texture, akin to the softwood surfaces, and consolidates the effort to create a continuous space that has always characterized Wright‘s work.