Engineering Department University of Leicester

Introduction

Opened in 1963 and considered one of the most important buildings from architectural point of view of its time, the Engineering Building of the University of Leicester, a project by architects James Stirling and James Gowan, is absolutely distinctive. It stands out among the oldest and newest parts of the campus, forming a third of the architectural triptych that defines the silhouette of the University together with the Attenborough Tower and the Charles Wilson Building.

Gowan and Stirling, in collaboration with engineer Frank Newby, created a piece of unique modern architecture, designed both for the specific needs of the Engineering Department and for the available corner of the campus.

The building is an early example of postmodernist design and continues to inspire architects today. Classified as Grade II (building with historical value) it was named among the ten best post-war buildings in Britain by Historic England in 2015, who described it as “a synthesis of traditional and modern elements that is totally British.”

Chronology

- 1957 – James Gowan and James Stirling design the new Engineering Building of the University of Leicester.

- 1960 – The signature of Felix Samuely and Partners begins construction of the building under the leadership of chief engineer Frank Newby.

- 1963 – Construction is completed. Staff and students move.

- 1988 – After 25 years, the glass in the main tower is replaced.

- 1999 – Important internal work to bring the building to the required fire safety standards. Also improvements for disabled access.

- 2015 – Mass renovation work begins. The building was named as one of the top 10 post-war buildings in the United Kingdom by Elain Harwood of Historic England.

- 2017 – The important general works are finished and the workshops are given a new roof.

Location

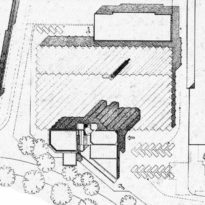

The building was erected on the Campus of the University of Leicester, England. Like many of the most ingenious buildings of the last half century, its construction was relegated to a surplus site, an unwanted corner and this instead of an inconvenience was an incentive since it provided architects with a stimulus and a challenge to rise above of the immediate circumstances caused by neighboring buildings without character.

Concept

The demands of the client were clear and mandatory: the laboratory workshop space had to be completely flexible in its partition to allow the subsequent change dictated by new experimental demands. However, these same spaces had to be illuminated by the northern light, since the delicate machinery discarded direct sunlight, which would have interfered with its accuracy.

A part of the structure should be at least 34.50m high to accommodate a water tank whose content would be required for hydraulic demonstrations at ground level posts and laboratory areas. Finally, the architects were asked not to use concrete finishes exposed outside. With this last request the architects agreed since they agreed that the concrete surfaces were not appropriate for the British climate. Out of this clash of sites, functional demands and architectural temperament, the Leicester School of Engineering emerges as a vital and almost impeccable solution.

This building is the strictest application of the idea that the form follows the function, so much so that each element and form responds directly to a specific function. It has numerous allusions to works of architecture of the British Modern and Industrial Movement, since the materials and methods used in this school are very similar to those of industrial buildings built at the beginning of the 20th century in that country.

Spaces

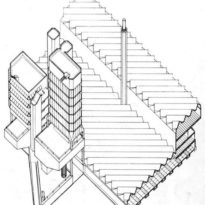

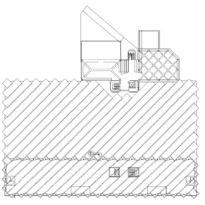

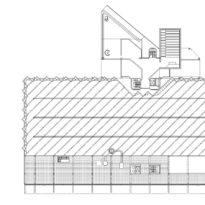

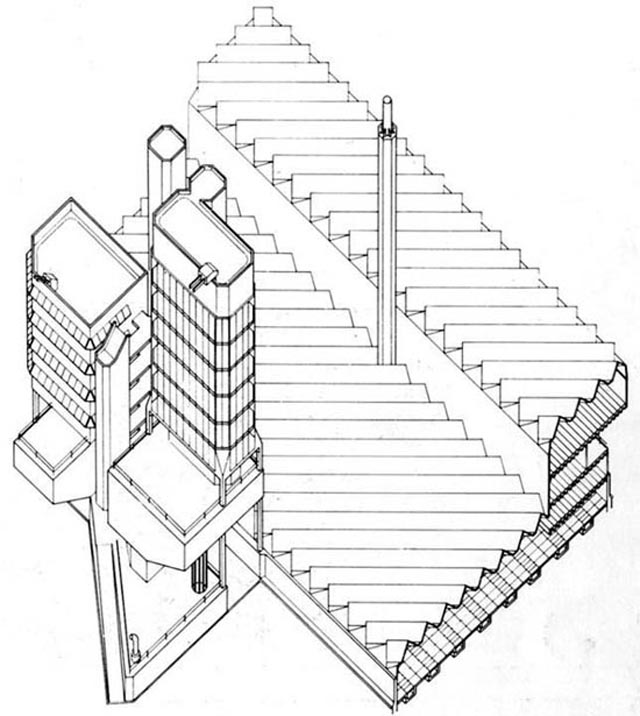

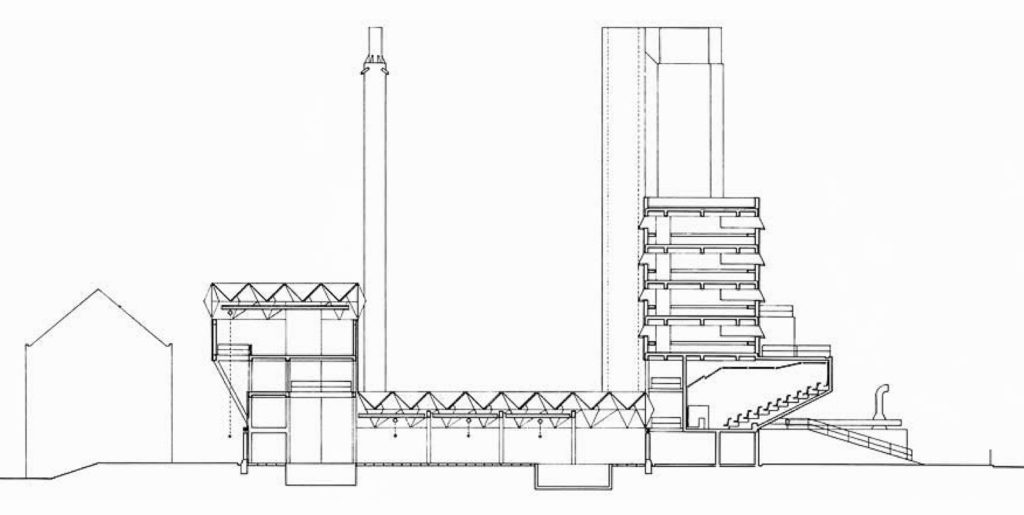

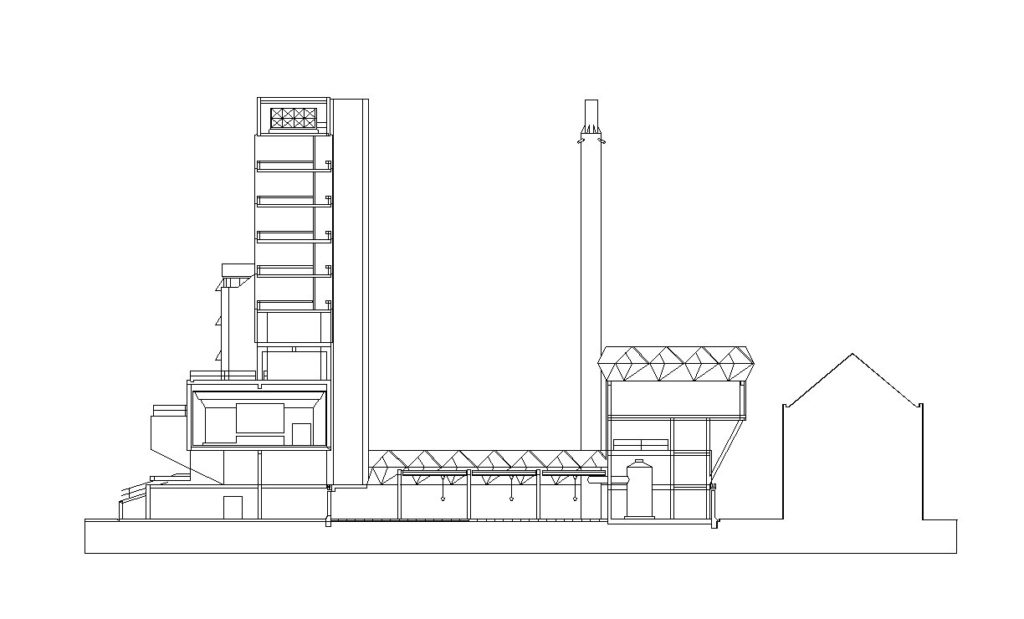

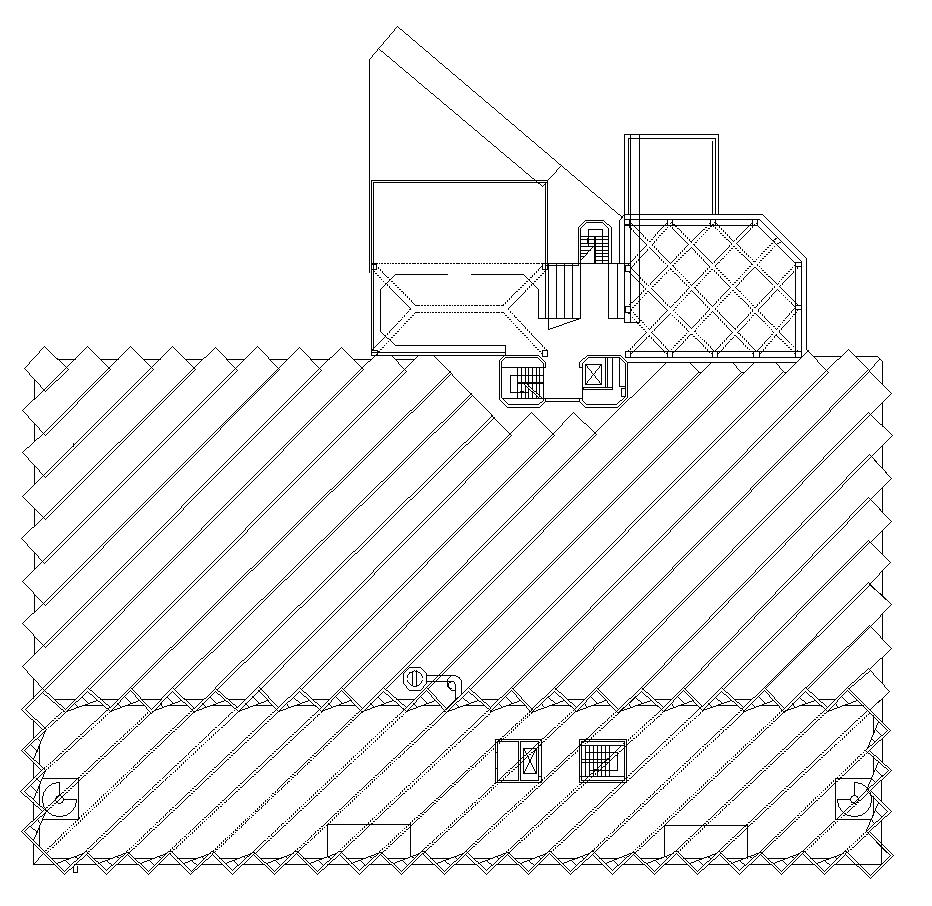

Designed to strictly fulfill its functions at amazing levels the Engineering Building comprises large workshops at ground level, prepared for heavy machinery, covering most of the available site and a vertical set consisting of office and laboratory towers, rooms of conferences, stairwells and elevators.

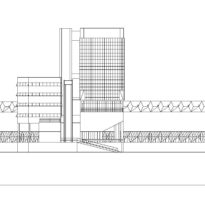

At the top of the two conference cantilever rooms there are two towers together that contain laboratories and offices and whose design is inspired by the superstructure of an aircraft carrier. The rooms hold the two linked towers that contain laboratories and offices.

The location of the laboratory building is on a plot with too many buildings and services with the only advantage that a public park is dominated from its windows. The place is so small, so irregular and so full of buildings that it was inevitable that at least part of the construction would rise. As a result, a strange and irregular building was built that extends over a secondary road that borders the park. The way to use the space in a complex way, crowding a set of towers on one side, indicates the efficiency of its construction together with the use of materials normally used in industrial works that, although they could be used for economic reasons, appear visually rich and opulent

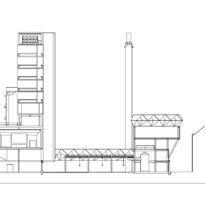

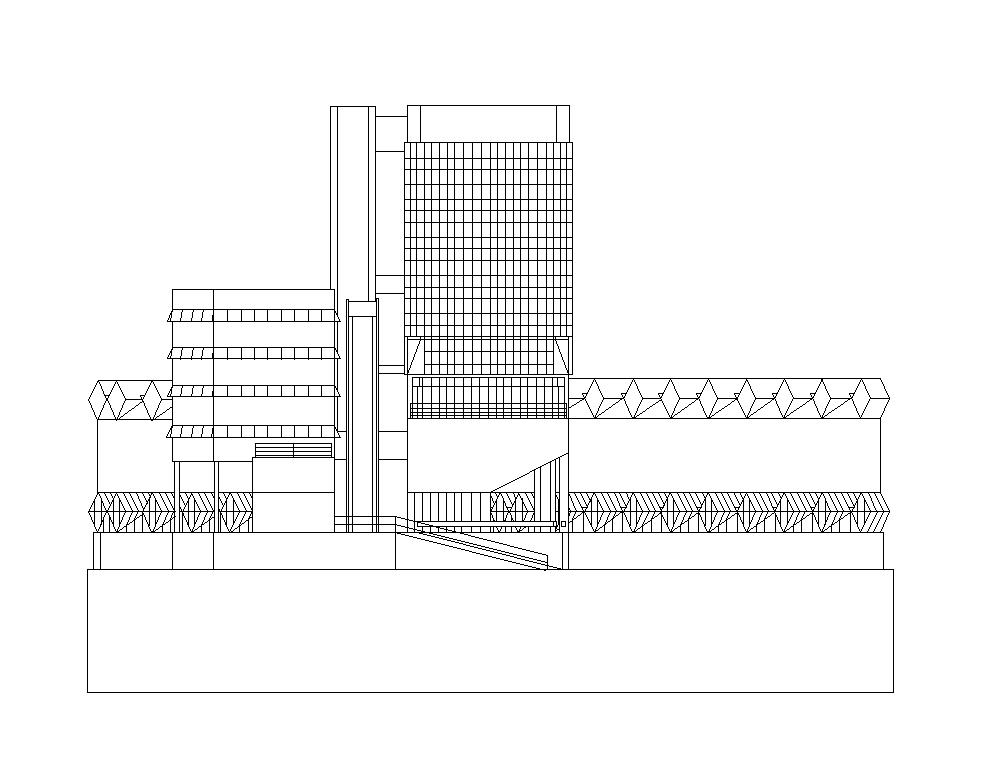

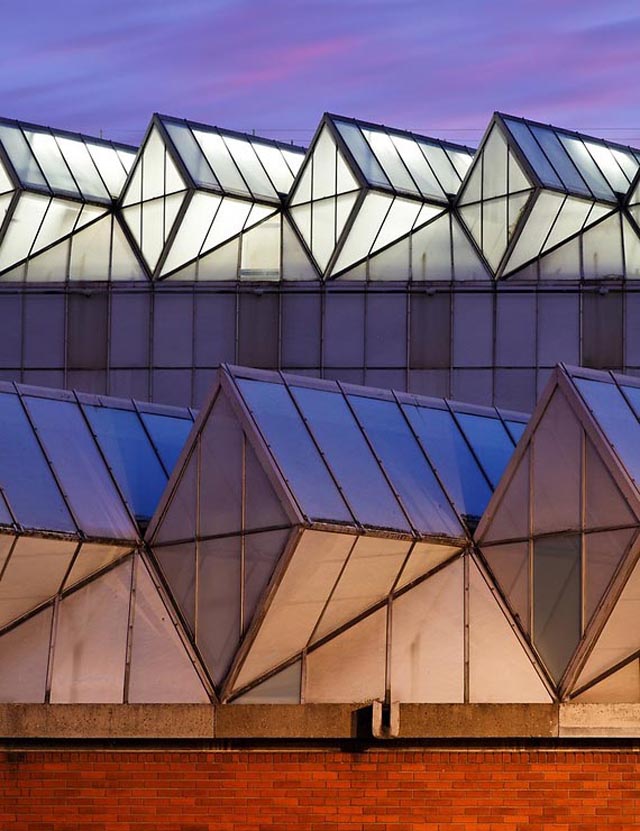

The buildings on the ground floor have large roofs formed by undulating “waves” at a distinctive angle of 45º with respect to the towers, to allow northern light to enter indirectly as this could affect the delicate instruments. These roofs similar to factory ceilings cover workshop and laboratory areas. The workshops, which covered two thirds of the area, had to have glazing with northern light, but the plot does not run from north to south. Then, while the building uses its site efficiently, the glazing runs diagonally, developed by Newby as a low-cost solution, but denoted by intentional diamond-shaped terminals designed by Gowan. The interior is overwhelming due to the resulting bright and translucent light.

Next to the workshops there is a fairly tall and thin tower that houses the school offices. This height is due to the fact that at its top a water tank has been installed that is installed to create a large waterfall necessary to do experiments in the workshop. In the lower part of the tower is an auditorium that stands out whose facades are supported by two thin columns that reach the ground. Under the auditorium is an external spiral staircase lined with glass. In the lower part of the other lower tower, whose corner is slightly curved, there is another auditorium with characteristics very similar to the previous one, with the difference that the outer pillars that support the tower do so also with the auditorium.

The workshops take out a chimney of the same height as the office tower and serves to remove the vapors without disturbing the users. Next to the office tower another lower building also houses laboratories.

Visually it may be surprising, also practical, but the complexity of its design makes the Engineering Building very difficult, and therefore expensive to maintain in a good condition, a situation exacerbated by the restrictions of its Grade II listing. The most important restoration work was carried out in 1988, 1999 and 2015-2017 and consisted of replacing the impressive translucent glass roofs and facades originally designed by Stirling and Gowan while the existing construction services were renovated and improved.

Description

The main structural framework is built with flat reinforced concrete slabs.

The restrictions of the place designated for the construction of the building together with the demands of the client shaped the design of the architects. The client’s demands were clear and mandatory: one of them was that the laboratory workshop space had to be completely flexible in its partition to allow the subsequent change dictated by the new experimental demands. However, these same spaces had to be illuminated by the northern lights since a delicate machinery discarded direct sunlight, which would have interfered with its accuracy.

The building, a low structure that covers the floor juxtaposed to a group of slightly balanced towers, which directly meet the two requirements of north light and height, has a readable shape. It can be recognized for what it is from almost every angle. Their lines and masses together have a scholastic and technocratic character, which express their purposes to the observer. The shape is rich in color and surface, but its forms are never free and, even more, none of them seems fanciful, despite its novelty. It is a functional building that seems functional, an industrial-style laboratory and classroom, which gives the appearance of being just that, a factory for study.

The partition of the building is due to the use, present or future and to the site. The tower arose due to the need to use the northern light and because a column of water with a great fall were some of the client’s requirements. The diagonal placement of the ridges to capture the northern lights was dictated by the fact that it was impossible to place a building oriented directly north of sufficient surface in that narrow place. Subsequently, this 45-degree forced angle was allowed to influence other details of the building, especially the tower complex, even if only for a desire for visual harmony. From these incidents, the architects created a coherent, original and unpredictable vocabulary.

As a consequence of these adaptations to the circumstances, and the way in which many details were created, a strong visual image emerges whose memorable impact is rare even today in a climate where images with character are sought in the designs, even without programmatic justification. Finally, the Leicester Engineering Building conveniently solves the often controversial concept of “form versus design” in a convenient way.

Materials

The glasses on the ceilings of the laboratories, approximately 2,500 panels, are of two types: translucent laminated glass with an inner layer of fiberglass and opaque glass covered with aluminum. The distinction between the two only becomes visible at night when the building is illuminated. Stirling and Gowan placed these panels at a 45 degree angle, creating rows of diamond-shaped skylights that give light to engineering research laboratories from the north.

The walls of the building are made of Accrington red brick and the roofs with Dutch red tiles. A curious feature is that some of the doors that face the outside are also covered with fine red bricks.

Within the workshop space on the ground floor, which can be divided to provide flexibility, the floor is a series of concrete slabs that can be removed to reach the foundations depending on the machinery used.

On some of the interior floors red rectangular tiles were placed and some details of the concrete structure were exposed.