Atlantida Church

Introduction

The project of the Church of Christ Obrero, near Atlanta, one of the seaside resorts of the coast of Uruguay, was entrusted to the engineer Eladio Dieste in 1952.

Location

This is not the church for the city and its tourist population of a season, but for the people’s economy, which is stablized through the tourism market. The town is, as described by Dieste, “one of those groups that do not become a village and show that, with the clarity of massive architecture, disorder and injustice in our societies: it is a nation of workers and peasants that supply the town with lettuce, of masons and girls of service.” So no surprise that the project called for an engineer, and then to a specialist in economic and operational decisions of sheds and utility buildings, if one understands and specifically asks for a warehouse that can be used as a church.

Concept

Christ Church was an initial work. Dieste called it “my first architectural experience” and it is clear that the project raised many problems. In it, the architect expressed certainly the possibility of his experimentations with the brick laminate, but also strove to build an architectural language of the codes set out on the technological possibilities of the developed countries. All works of Dieste stick to formulas handed down by constructive rationality, but to uncover manipulation from these formulas, making scientific and empirical experience in stunning objects, and always checking in its broadest sense and strong, the notion of architecture as loyalty to the place.

Dieste’s response is an exceptional project, that very early poses problems that are going to make appearance in the Eighties around the ideas of postmodernism and regionalism. Christ Church shows the possibilities of extending the modern project from the periphery to the center at which it originates, as well as opens Dieste’s work for further development.

From the privacy of devout Roman church or the elegant lightness of Gothic cathedrals, the originality of style seem to be present in Gaudí’s architecture and Dieste, creating a repeating image in the creative role of man and his implementation in the spaces. Every piece, every brick, every man is a part of all, a lightweight support that is built with reason and thought, adapted to its environment and opportunities, noting that the models were exported and dehumanized in the proper context. It does not fulfill the social function that the genius of Dieste wanted to transmit.

Spaces

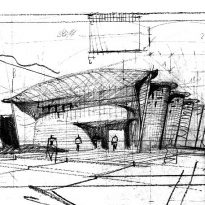

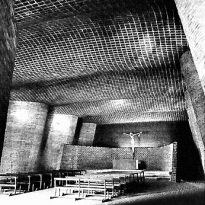

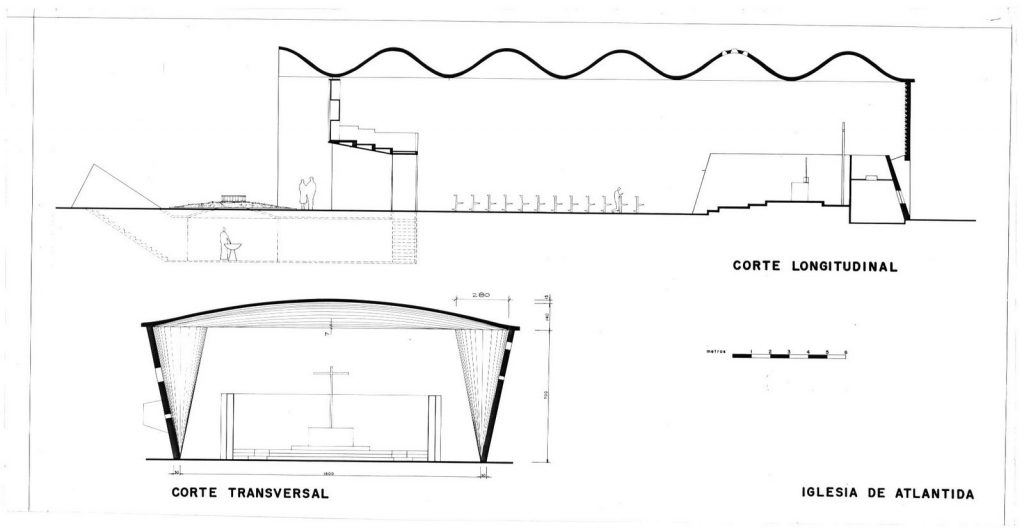

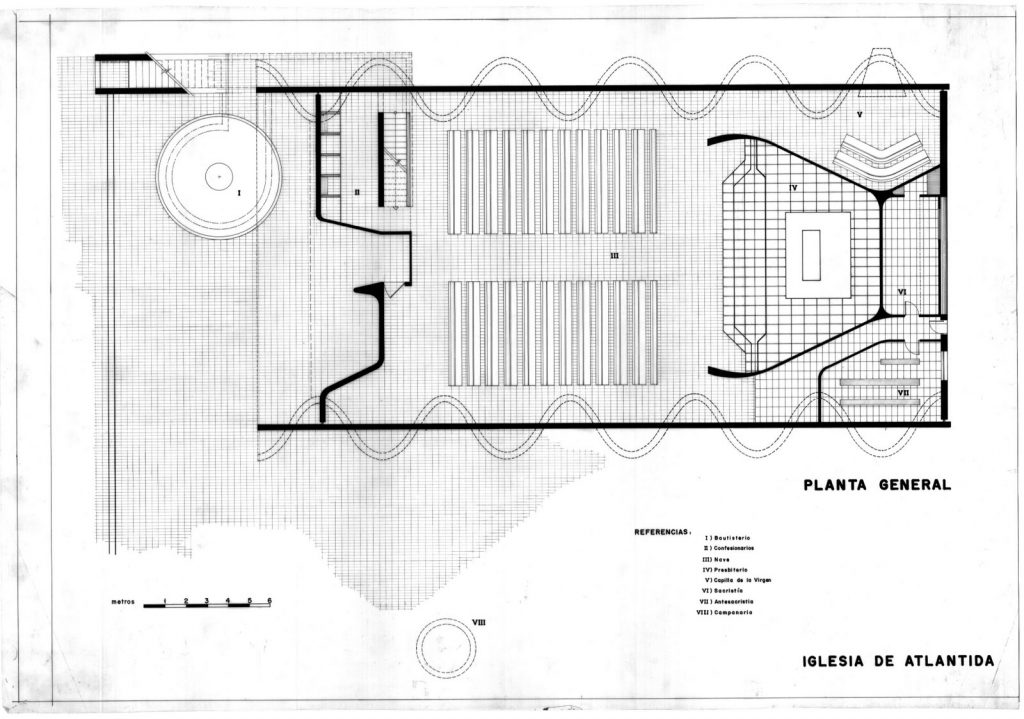

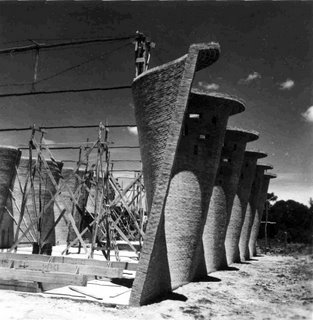

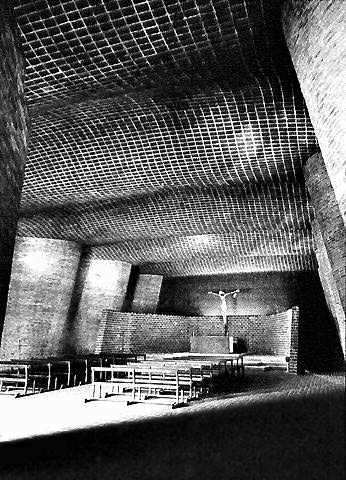

Workers for Christ, whose cost was “more of a warehouse,” Dieste built an extraordinarily complex object of architecture and formal technology, setting up a deep cross from the programmatic aspects of the church and the expressive possibilities of its research. Designed as a rectangular nave thirty feet long by sixteen feet wide, covering nineteen meters in height at its widest points. The wavy line of the floor is repeated and magnified in the surprising side walls, built as a succession of half-cylinders of seven meters high, straight at the base and wavy on top, with irregular holes closed with colored glass. The union between the rolling surfaces of the floor and walls introduces a particular instability that causes strange effects of the layers of brick in sight.

At the entrance, the mezzanine of the chorus divides the wall of the facade into two bands. The bottom of the sheet is folded asymmetrically into a brick access and space for the staircase to the choir. At the top, with the net cropped area of the three rows of flat displaced Dieste accentuates the fluidity of the curved blades of the rest of the building. At the bottom of the vessel are located the sacristy and the chapel of Our Lady of Lourdes, behind the curved wall that surrounds the pulpit and presbytery, and its walls reach the ceiling. Dieste creates a deep hole that becomes visible on the bottom of the nave. In this way, the perceived friction between the interpretation of the sanctuary as a place of “higher density spiritual” and the notion of church as community space are equal; they choose to unite the area of the vessel and indicate the density of the spiritual priesthood via exposure through curve of the blade and the depth of indeterminate space behind it.

On the outside, the side walls construct a rarefied landscape of repetitions. In its design, it manages to reveal Dieste’s opinion that the expressive possibilities of the brick material as universal, and more on the inside, the constant changes of light on the surface of the half-cylinders deepen, while discovering the extraordinary formal effort.

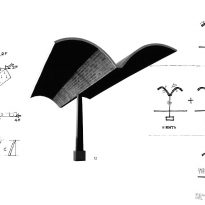

The ensemble is completed with a parish bell tower designed as a perforated cone over its entire surface on one side of the church and the other with triangular prismatic volume of stairs to the underground baptistery, with a circular area, covered by a dome and a lantern-lit onyx.

Structure

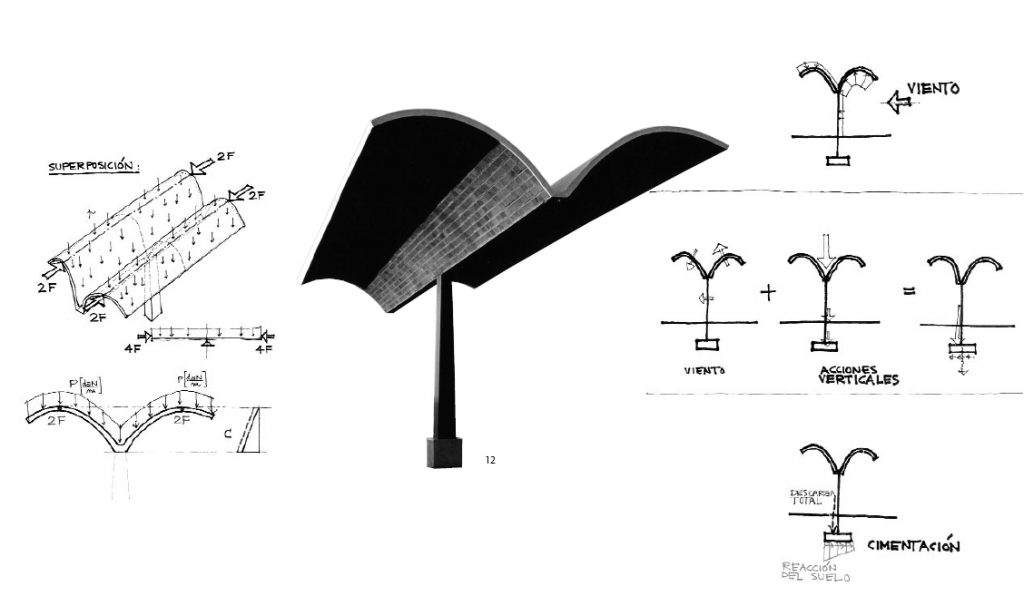

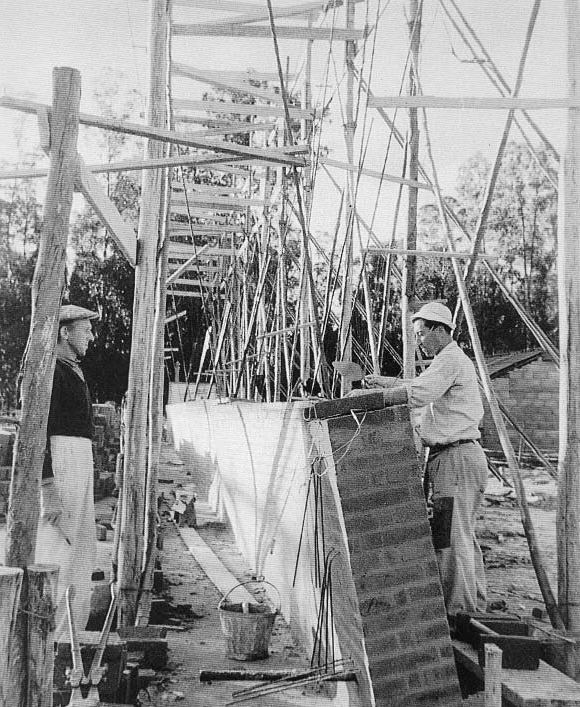

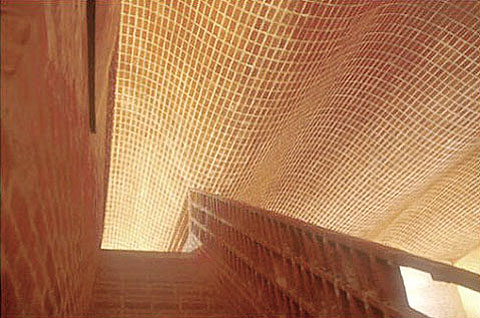

The walls and surfaces are covered with thin and folded brick laminate, designed by Dieste, and are so slim that never before had anyone been able to achieve the effect with traditional materials. This shows his constructive ingenuity and skill, contrasting sharply with its contemporary architecture (Le Corbusier and Candela, among others), made with reinforced concrete.

Dieste’s method of building can be seen as a clear advance in sustainable architecture, for its effectiveness in the use of the material.

The unique works of Dieste can only be understood from the technical leaps made in the masonry, and so one must be able to put aside previous knowledge acquired of the traditional construction of the land and materials.

The “union” has been among the essential parts of any structure to ensure its stability, giving the successive pieces relationship, avoiding at all times to make vertical stripes a continuity.

The “equipment” was established as a reliable way to safely and consistently to achieve the “union” among its parts, thus generating a constructive pattern characteristic of each type of gear and place (in English, a cross gear, a Belgian gear, a blight on the Spanish, etc.)..

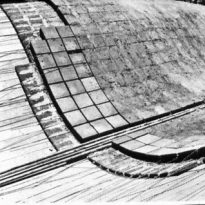

The thoroughly traditional placement of the bricks joined to each other, keeping a predetermined joint in the masonry, disappears completely in the architecture of Dieste; it adds to it a new component, “steel” in bars or wires, which is included in a regular and uniform manner throughout the plan.

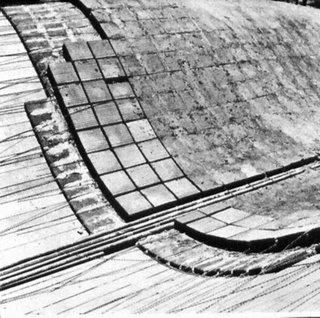

To do this, Dieste has in all his works, when it suits, arranged the pieces without joints, which generates a bidirectional graticule between the pieces, where are located the wires or bars of steel, weaving around the whole building a ductile material, rather than working with disjointed pieces.

This allows him to create what Dieste calls “structural ceramics,” where the proportion varies depending on ductility to generate the force or local pressure that is required for tension or compression in the masonry.

Materials

Eladio Dieste had begun to explore the problems of the vault until 1945, as a result of his professional collaboration with Antonio Bonet. The experience in the construction of reinforced concrete vaults him led to his experiments with brick in the construction of laminate surfaces. Anchored in sound theory and mathematical calculation and applied to the construction and design, Dieste focused his exploration in the operational design of the brick as an organizer of the structure. If it worked on the Christ Church, its production constructed a paradigmatic formal universe certainly missed in the orthodox modern lexicon; it is true that constructive virtuosity was to be found under its expressive possibilities. To Dieste, a sound architecture can not happen without a rational and economic use of construction materials.