Amsterdam Orphanage

Introduction

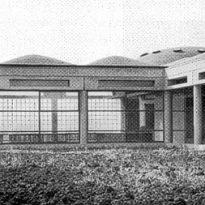

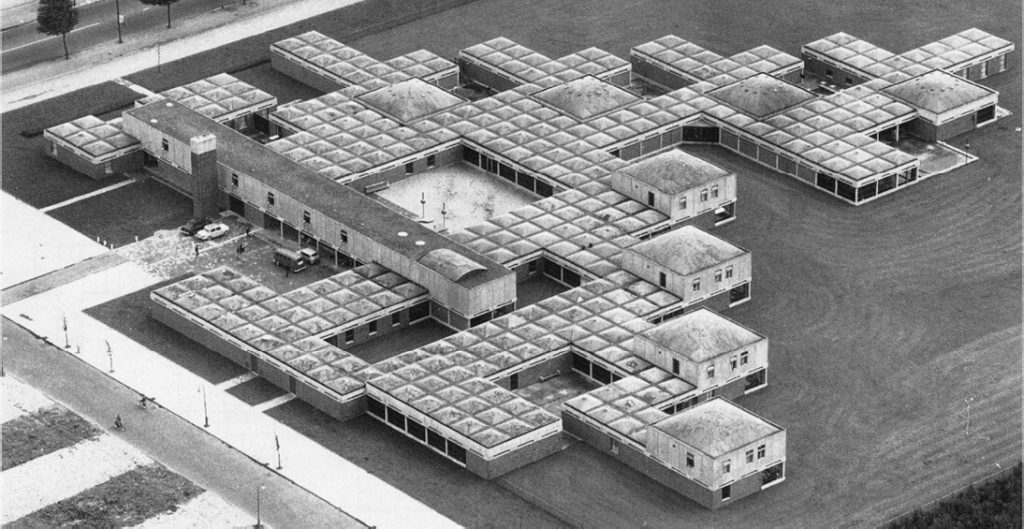

A cult building in the 1960s, Van Eyck‘s orphanage brought to the surface an idiosyncratic interpretation of modern architectural ideas enriched by patterns and shapes and by the balance of repetitive pavilions. Van Eyck’s reputation as an original designer was enhanced by the orphanage built in a place in the suburbs of Amsterdam and has influenced school buildings around the world.

The building looks like a “casbah” (citadel) or a labyrinth. It is composed of innumerable interior and exterior spaces, which are interconnected in a complex order and merge into each other almost imperceptibly. In Van Eyck’s view, the private and the collective were closely linked and the boundary between the building and the city had to be disjointed.

In 1986, a plan to demolish the orphanage was announced. A large-scale campaign, which attracted international support, prevented demolition. The complex was recovered thanks to a real estate developer who wanted to buy the building and the site, provided that it could develop an office complex there. This complex, called Tripolis, was designed by Aldo van Eyck and his wife Hannie in 1991, in the former playground of the orphanage. They also performed the restoration of the orphanage. Much of the original program buildings and functions were removed or changed. Three of the spaces specifically made for the children were restored in memory of what once represented the building.

In 2014 it was declared a National Monument, but the masterpiece of Dutch structuralism has become obsolete and abandoned.

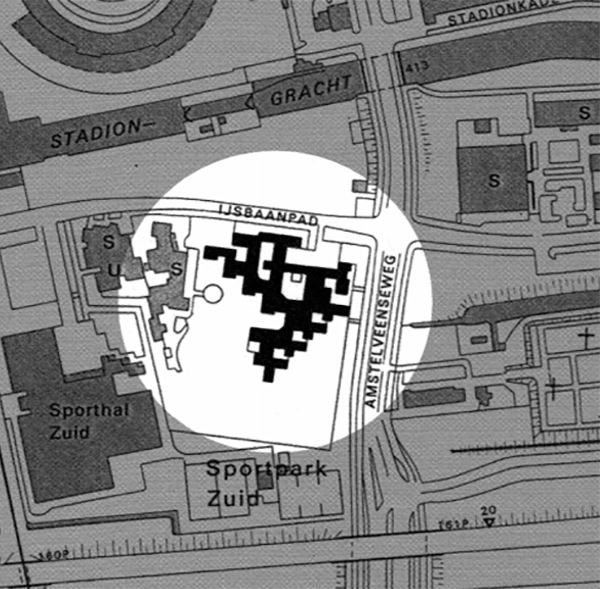

Location

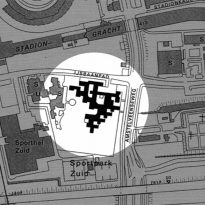

The building is located on the southern outskirts of Amsterdam, IJsbaanpad 3B, Holland, an area that at the beginning of the 20th century was influenced by the South Plan proposed by H.P. Berlage for the extension of the city. It was located between the A10 motorway and the Olympic Games Stadium in 1928, on a flat lot without neighboring buildings.

Concept

The orphanage devised by Aldo van Eyck quickly became known throughout the world due to the exemplary concept of the building, a home for 125 children of all ages, articulating a revolutionary synthesis in the consideration of the individual and the group, the inner and outer space, Of large and small areas. Van Eyck readopted a concept previously formulated by the fifteenth-century architect L.B.Alberti, the analogy between house and city, “a small world within a large, large world within a small one, a house as a city, a city as A home “, creating a home for children was the goal of Aldo van Eyck.

Van Eyck focused on the development of the project in balancing the elements that allowed him to create a house and a small city at the outskirts of Amsterdam.

As a member of CIAM (International Congress of Modern Architecture) and later founding member of Team 10, van Eyck held strong views on postwar architecture. The Amsterdam Orphanage was the architect’s opportunity to put his views into practice through his first large-scale large-scale project.

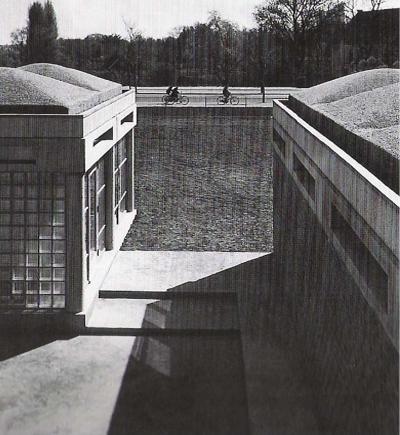

“… The building was conceived as a configuration of clearly defined intermediate places, which does not imply a continuous transition or an endless postponement with respect to place and occasion. On the contrary, it implies a rupture with the contemporary concept of spatial continuity and The tendency to erase all articulation between spaces, that is, between outer and interior, between one space and another.In contrast, I tried to articulate the transition through defined intermediate places that induce the simultaneous awareness of what is meant on each side … “(Aldo van Eyck)

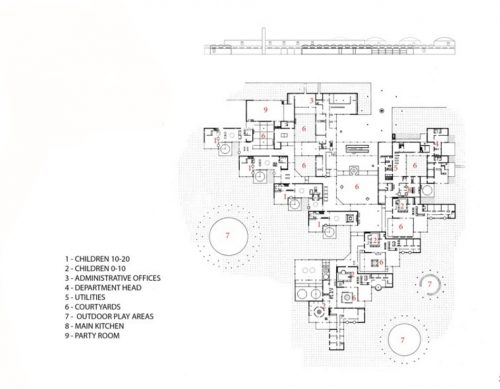

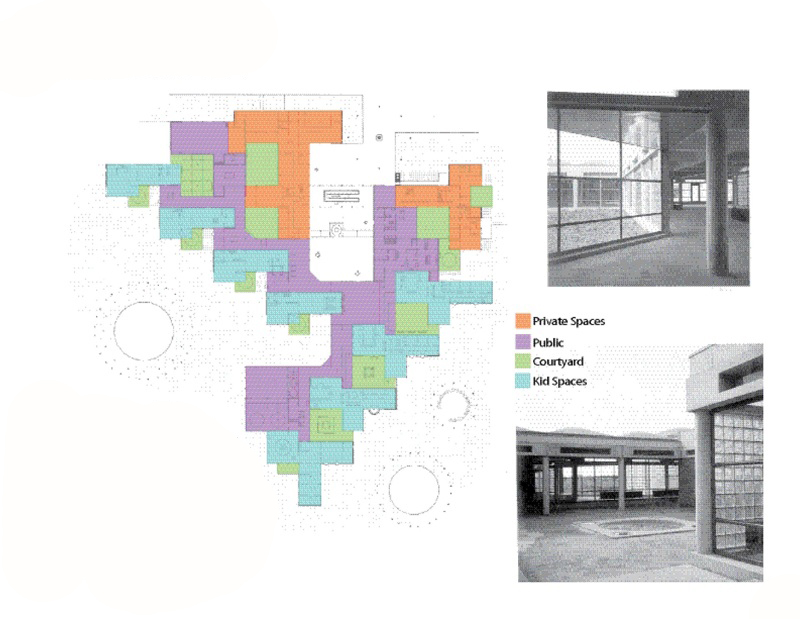

Spaces

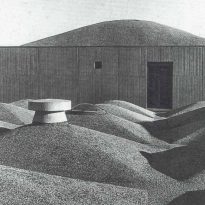

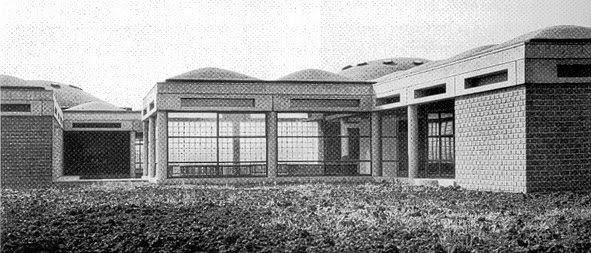

After a decade of experimentation with elemental forms and their interrelations, Van Eyck’s views were synthesized in an iconic building, the Amsterdam Municipal Orphanage. In it he managed to reconcile a great quantity of polarities. The Orphanage is a house and city, compact and polycentric, unique and diverse, clear and complex, static and dynamic, contemporary and traditional, rooted both in the classical and the modern tradition. The classical tradition lies in the regular geometric order found at the base of the plan. The modern is manifested in the dynamic centrifugal space that crosses the classical order. The archaic tradition appears in several aspects of the formal appearance of the building. Due to the soft biomorphic domes that cover the different spaces, the first impression it evokes is that of an archaic settlement, reminiscent of a small vaulted Arab city or an African town.

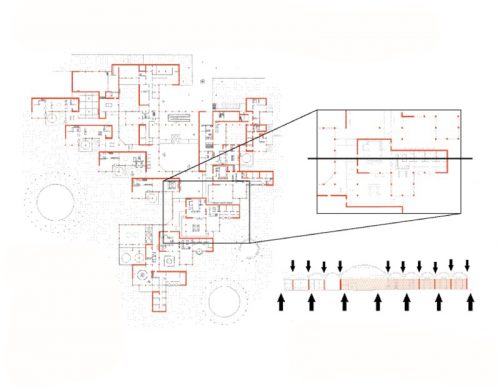

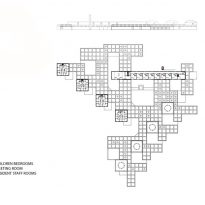

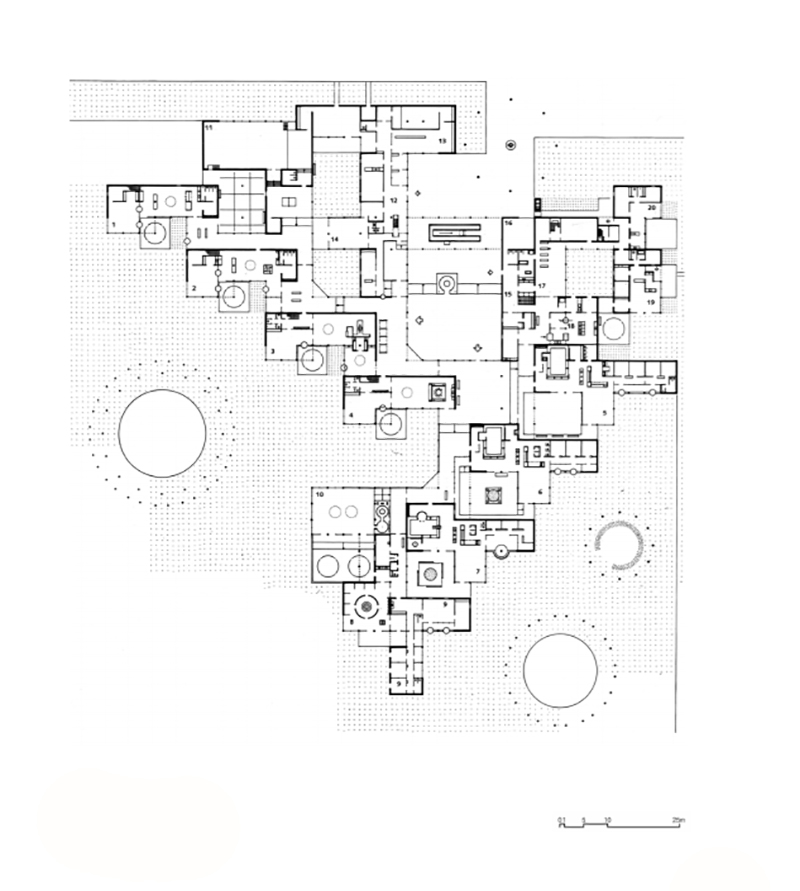

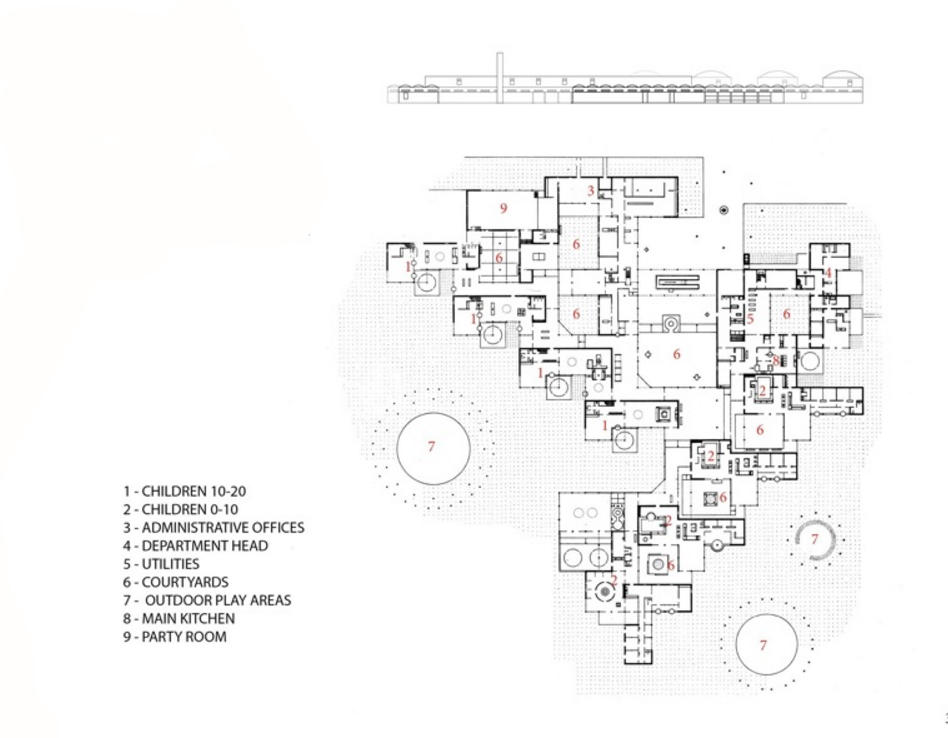

The design reconciles the advantages of a centralized structure with the decentralized pavilion patterns. The system of pavilions with two module sizes is transformed into a continuous, but perforated volume, within which both the pavilions and the main block are identified. The smaller modules were used for the residences and the larger ones for the common spaces.

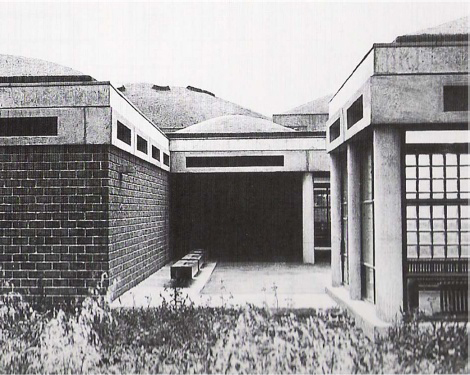

Courtyard

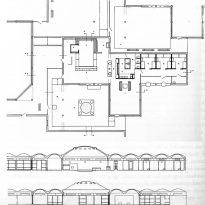

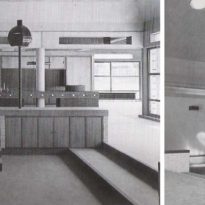

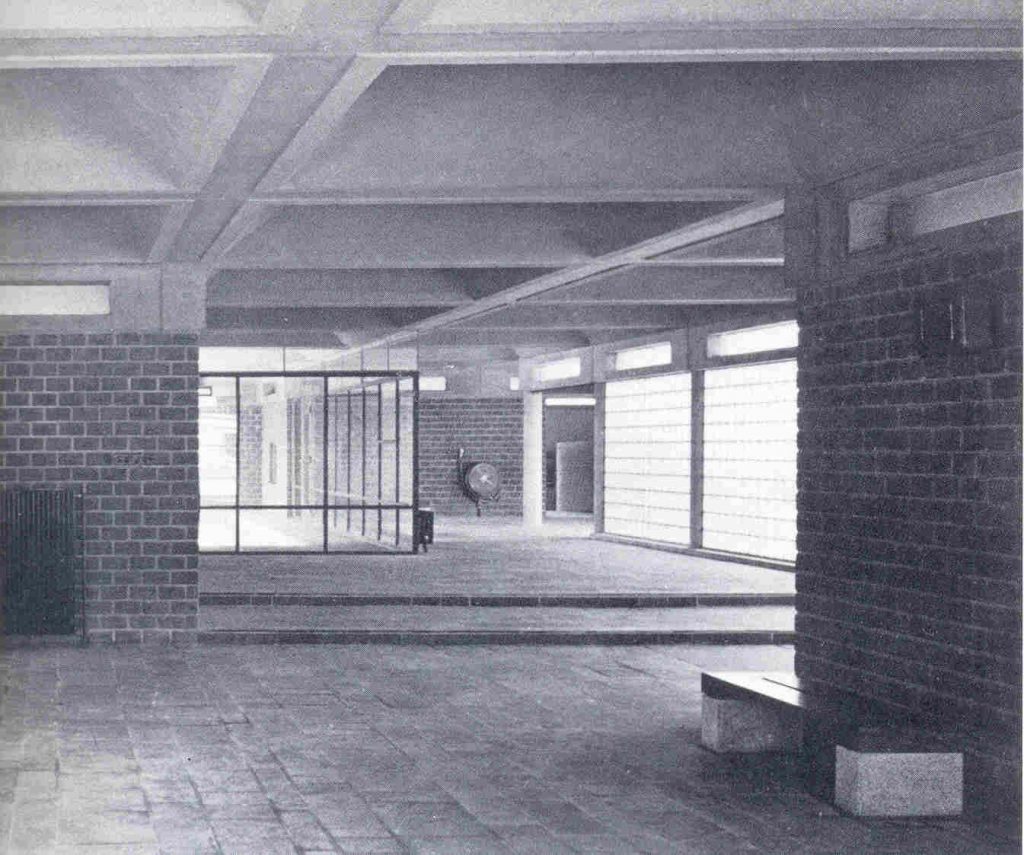

The access courtyard is next to a large hallway that intersects two inner streets and appears to be a modern version of a Renaissance “cortile”. The inner streets sometimes remember the Romanesque cloisters. A linear block of administration separates it from the large central void that is the heart of the place, with intermediate places. A courtyard with enclosed spaces that are combined with others open or semi covered creating a large square from which access to the main areas of the program.

All spaces are related to the center established by the large domes of the inner courtyard, the axial lines of the grid generated by the small domes and the doors placed axially. However, the “immutability and rest” of the classical tradition is assimilated and traversed by the dynamic order of the new reality. The centrality established by architectural “order” is limited to the spaces mentioned above, and is countered almost everywhere, both in the design of the specific equipment and in the overall composition. The focus of the inner courtyard is a circular seat marked by two lamps, which instead of occupying the geometric center of this space move about 4 meters diagonally. And if this place is in fact the center of the whole settlement, it does not dominate as such since the different volumes are dispersed in all directions, becoming the fixed point from which it develops and delimits the decentralization. Therefore, the axial ordering of the square does not extend in any way to the areas of internal circulation. It simply provides the initial impetus for the two inner streets, which branch into contradictory zigzag movements to give access, through inner and outer courtyards to the various units. Consequently, the residential units that are developed along these streets are not in any way united by a central perspective.

Residential Units

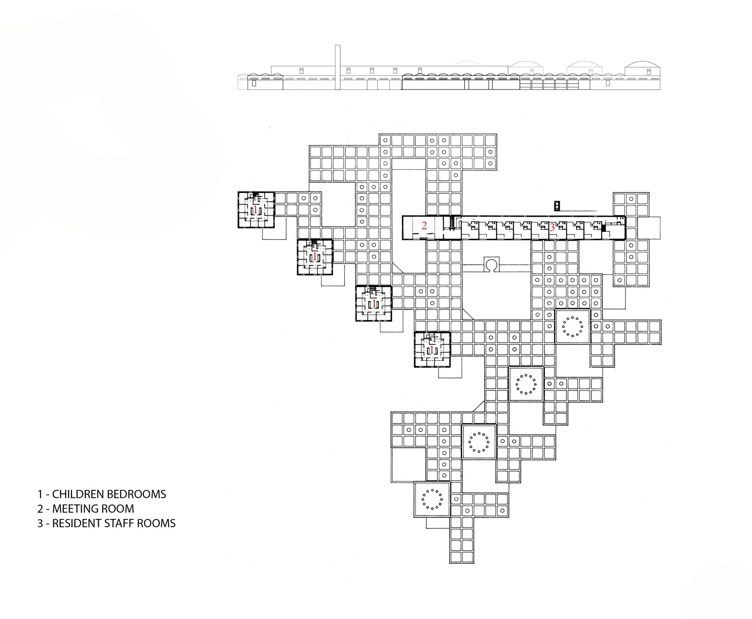

The residential units are arranged in a staggered formation, thus allowing each of them to have communication with an individual outdoor space and with the internal street. The result is a polycentric building, with a joint of large and small spaces, inside and outside, in successions of units, sets of 9 modules, each defined in its own right, while it is interlaced rhythmically, also with domed covers in This case greater.

The design of the orphanage was a reaction to the architecture of the fifties, with its massive constructions of houses usually identical. The industrial architecture of the time provided little room for individual expression. With the orphanage, Van Eyck sought to recover individual architecture by repeating elements, creating a non-standardized plane, seeking new relationships between interior and exterior spaces, devoting attention to detail to empathize with the children who would live there.

Structure

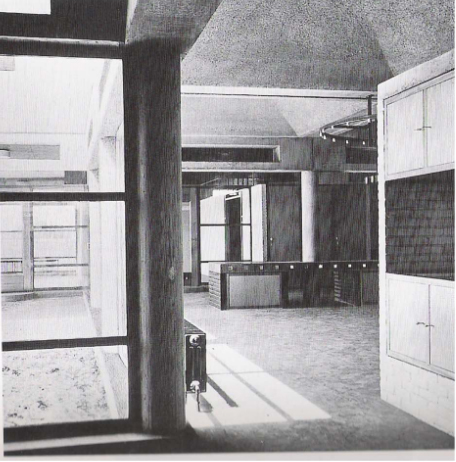

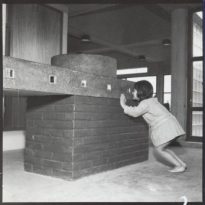

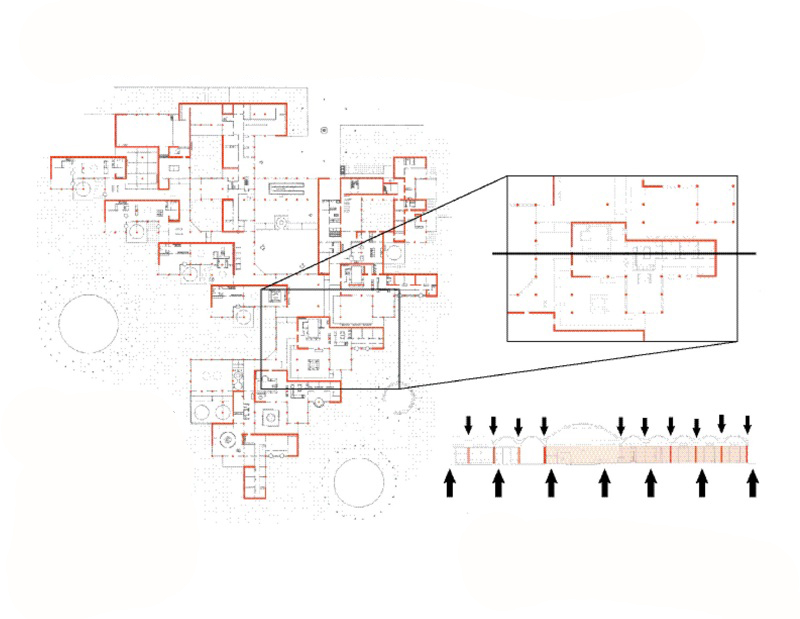

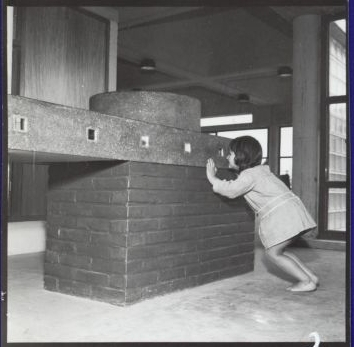

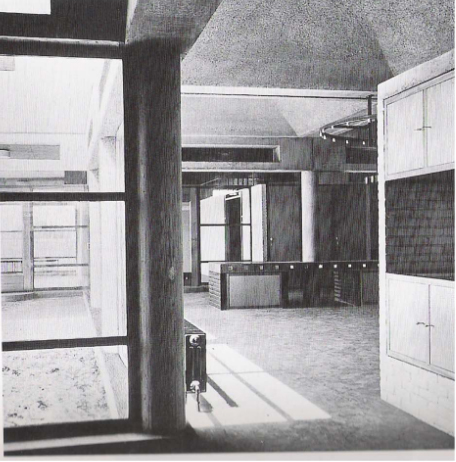

Underneath the architectural balance that is offered to the sight is a strictly confirmed architectural order, consisting of columns, cargo walls and architraves that combine to form an orthogonal grid. The roof domes at the top of the grid provide continuous spatial articulation.

The geometrical order of the building is articulated by a contemporary version of the Classical Orders, composed of columns and architraves. The columns are thin concrete cylinders with the fine grooving on the left side of the formwork. The architraves are concrete beams, each with an oblong slit in the center. Its united extremities give the impression of a capital, although the capitals as such are absent.

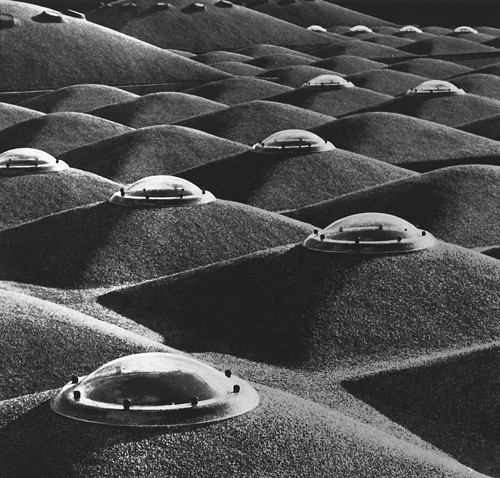

In the design of the pavilions that make up the building, Van Eyck uses standard modules that are repeated with subtle variations. The complex comprises a total of 336 modules formed with round columns at the corners and grouped around an inner courtyard, covered with precast concrete convex ceilings and above domes of a synthetic material.

The small domes form a grid that extends evenly throughout the building so that the general pattern can be read at each point. Along the axial lines of this grid, pillars, architraves and solid walls mark a series of well-anchored and enclosed spaces: the adjacent lounges and courtyards, the party room, the gymnasium and the central courtyard.

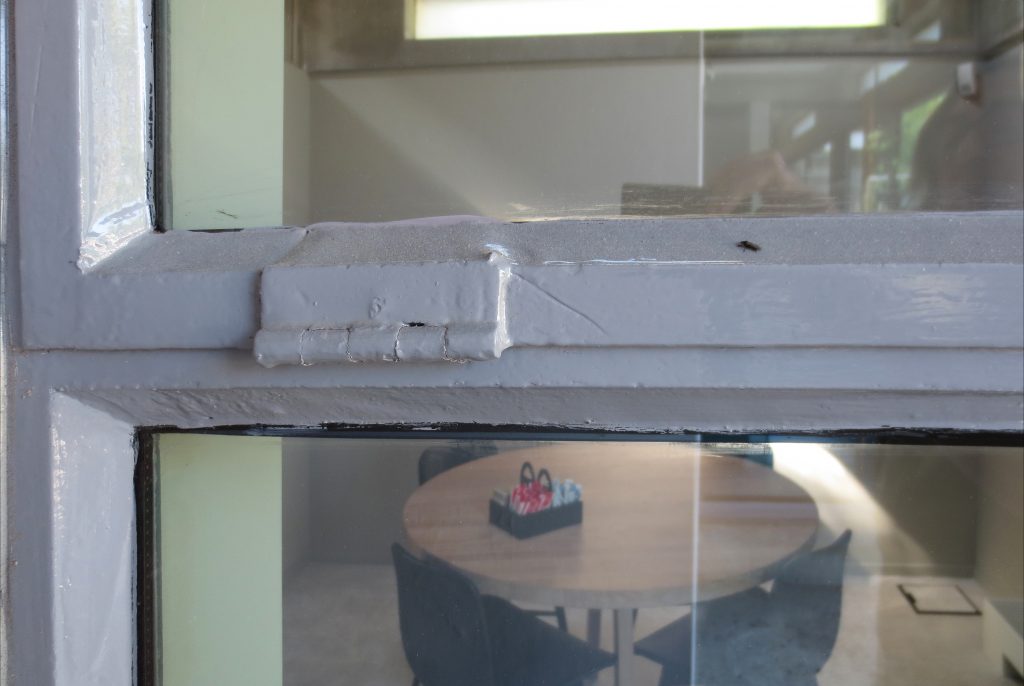

Materials

The buildings have been built with reinforced concrete panels and both opaque brick, dark brown, and translucent glass. The floors are also made of concrete.

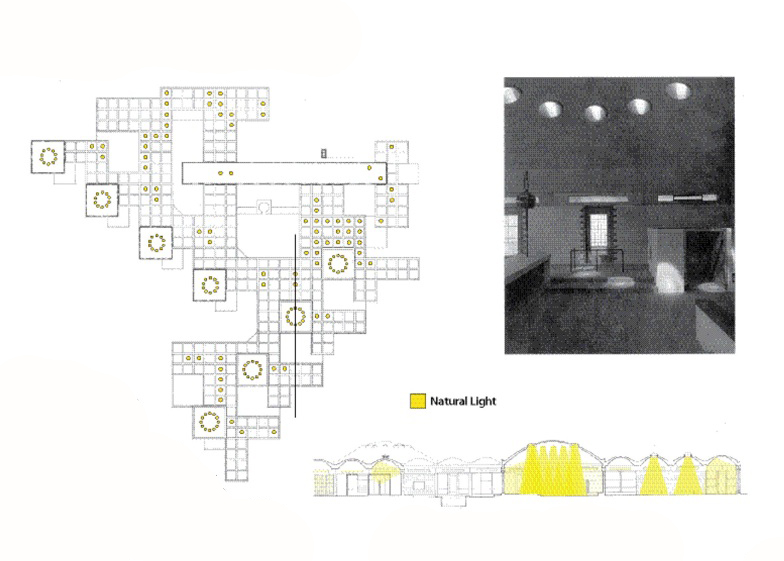

Domes

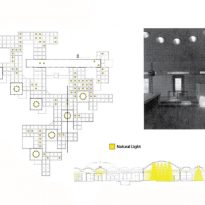

The central area of the project is covered with a hundred pyramidal domes of square base, 3.36m of side, prefabricated in concrete and some of them with a central skylight. The domes are supported by a grid of equal dimensions created by round pillars and concrete T-shaped jigs made in situ.

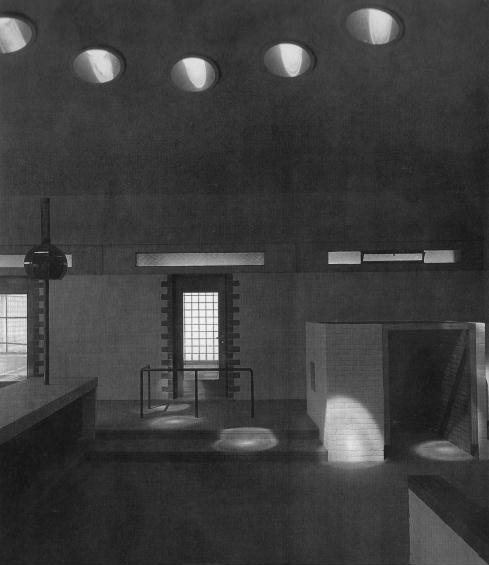

Skylights

Some of the domes are covered with skylights that allow the entrance of natural light. The rays of light penetrate the semi-dark rooms creating images of great visual interest. Along the main corridors are glass walls that overlook the many courtyards of the building, allowing for beautiful views, in addition to providing light to most areas of the orphanage

Video