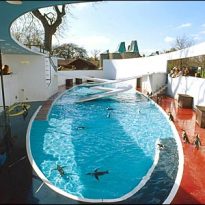

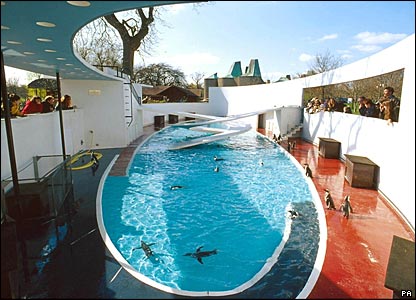

Penguin pool at the London zoo

Introduction

The Penguin Pool in London Zoo is a modernist monument and a feather in the cap of the Zoological Society of London. As well as being a building protected from the “art deco” style, it rises from the centre of the zoo’s park, having been subject to renovations in 1987, but without major changes in general since it was built in 1934 by architect, Berthold Lubetkin, and his company, Tecton, who were also commissioned to design The Gorilla House.

The Penguin Pool is a Grade I protected building within the scale of importance of the building protection scheme of the United Kingdom.

It was subject to restoration works in 1987, and was later converted into a water feature, as the penguins were moved to a larger space with a more natural habitat close to the Barclay Tribunal in 2004.

According to Chris West of the Zoological Society of London in an article in The Guardian, the penguins suffered joint pain due to having to walk all day on concrete, the pool was too shallow for the penguins to dive or swim, and they had no privacy.

Location

The Penguin Pool is situated in London Zoo, inside Regent’s Park, between gardens and beautiful listed buildings, which are part of British artistic heritage.

Concept

Lubetkin’s personal philosophy regarding the designs for the zoo was that they could be approached in two ways:

- Through a naturalist focus, in which he would attempt to reproduce as closely as possible the natural habitat of each animal.

- Through a geometric focus, finding a way to present the animals to the public in a non-dramatised fashion, in an atmosphere similar to a circus.

It is according to the second philosophy which Lubetkin designed The Penguin Pool.

It is possible that at the time of creating the project, the architect thought more about the spectacle than the penguins; more about the fantastic vision for the public than the stress that this would cause for the birds, to feel constantly observed in all their activities and in a way that (although novel and well-intentioned) only resembled their natural habitat in the colour of the ramps. Lubetkin was less concerned with the simulation of “freedom” for the animals and offering them a place where they could behave naturally, than with the visitor experience.

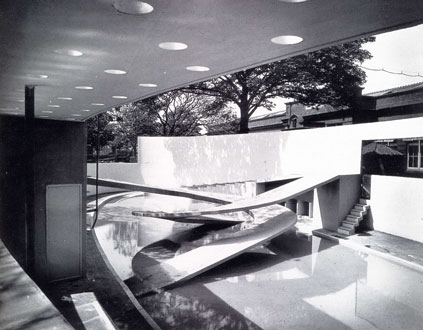

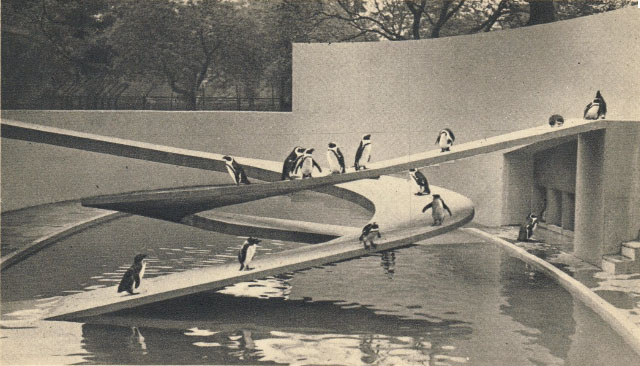

Based on an egg shape, the enclosure included two intertwined, spiral ramps, seemingly inspired by the propellers of an aeroplane or perhaps the playful forms of the Arctic.

Description

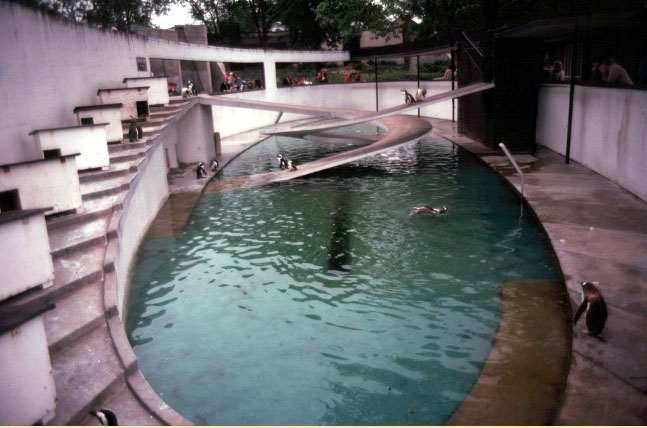

The general elliptical shape of the pool is accompanied by the intertwined spiral slides which connected the different levels. These arched ramps lend a dynamic appearance to the construction. The large, blue swimming pool provided the birds with a bathing area and lends to the whole a contrast to the white concrete which is used for the rest of the structure.

This construction wisely combines practical considerations, such as a shaded area for the penguins and smooth access slopes to the pool, with a broad aesthetic declaration of form and line.

The energy of the pool is concentrated on the two aerial ramps, in pure white which seems to perform a dance around the central oculus, which allow the observer to see in their joints, changes of direction and separations an image of the meeting point between the imagination, the mind’s eye and other unrecognisable perspectives between culture and nature.

This work of Lubetkin’s provides a visual representation of movement between the species, space and time. If, as he stated, life consists of taking part in a dynamic process of transformation, then his pool is an invitation to the same.

Spaces and Materials

The architect envisioned the opportunity to design a habitat for the penguins as one allowing them to display all their distinctive characteristics: gliding, kicking, swimming gracefully, nesting and the native calls of their species. Following the modernist method, he aimed to make the design adapt to the needs of its occupants. All these guidelines are executed and exhibited through the environment he went on to design.

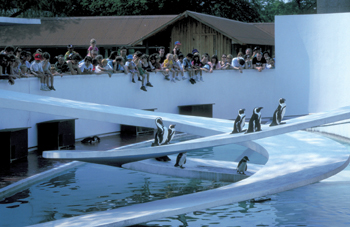

Firstly, the spectators could easily watch the penguins playing on the concrete steps which led to the ramps. From there, the penguins dropped onto their stomachs on the slides, emerging into the pool.

Ramps

The penguins were very active on the slides. It was the use of reinforced concrete that made their construction possible; a material which was a novelty at the time and could be used because the construction was exempt from the building codes in force in the City of London.

Diving tank

It was easy to watch the agile penguins diving, especially due to the contrast of the animals with the square mosaics on the bottom of the pool which made the blue of the pool appear startling.

Nests

The nesting-boxes were kept at the borders and corners of the enclosure, close to a tree which dropped its foliage and branches on the sand below, so that the penguins could build their own nests.

Walls

The high lateral walls of the pool, with their smooth curved forms kept the calls of the penguins inside them. Their sounds made echoes on the walls and could be heard throughout the area around the pool.

The Penguin Pool is particularly important as it was one of the first attempts to explore the creative possibilities of a construction material only recently available in 1934: reinforced concrete.

Structure

The entire structure which encloses the pool signifies a new rhythm of transformation. It is built from reinforced concrete and composes the large swimming pool, a diving tank and nesting-boxes. The whole installation is inside a large ellipse, with snaking slides, and surrounded by a wall at chest-height to allow spectators to see inside the enclosure. As in the Finsbury Health Centre and many other works of the Tecton group, the structure was designed by engineer, Ove Arup.

The area of the pool which faces South-West is closed off by a half wall, and to the west of the longitudinal axis the wall doubles in height. The taller wall extends toward the shallow stairs until reaching the top of one of the central ramps which hangs over and crosses the pool by its shortest axis, towards North. In this North part, on the wall, there is a large viewing window which extends around the pool to its opposite point.

At the end of the longitudinal axis, in the Eastern part, the structure has an eave, the canopy, perforated by three lines of regularly-spaced holes which allow for the passage of sunlight. This canopy is supported on three steel columns painted black, and continues before turning into the roof of the diving tank at the Southern point of the pool.