Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Assumption

Introduction

The current Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Assumption in San Francisco is the third church that serves as the archdiocese of the city. The first (1854) is still standing and is known as Old Saint Mary’s Cathedral, the second (1891) was destroyed by fire in 1962.

Immediately after that disastrous fire, Archbishop Joseph McGucken gathered his advisors to begin the process of planning and building a new cathedral. For such a project, the archbishop contacted three well-known local architects, Angus McSweeney, Paul A. Ryan and John Michael Lee, who began presenting preliminary sketches for the new cathedral that ranged from the traditional Romanesque mission to the Californian style. The plans soon took a dramatic turn as a result of a heated controversy resulting from an article written by architecture critic Allen Temko, who advocated a move beyond traditional architectural concepts to create a bold new cathedral, showing San Francisco as an important international urban center. To build a cathedral that would reflect the soul of the Californian city, Archbishop McGucken added two internationally renowned professionals to his team, the Italian Pietro Belluschi, dean of the School of Architecture of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who was in charge of the designs and Pier-Luigi Nervi, an engineering genius from Rome, who took care of structural concerns.

In August 1965, the ground began to be prepared and the apostolic delegate Luigi Raimondi blessed the cornerstone on December 13, 1967. The building was completed in 1970. The new cathedral was formally blessed on May 5, 1971.

Location

The cathedral is located at 1111 Gough St, San Francisco, United States, on the top of the city hill, in the neighborhood known as Cathedral Hill.

Concept

In addition to reaffirming the status of San Francisco as an international urban center, the new project should reflect the greatness of the city by incorporating the new liturgical directives promulgated by the Second Vatican Council held in Rome.

Liturgical directives

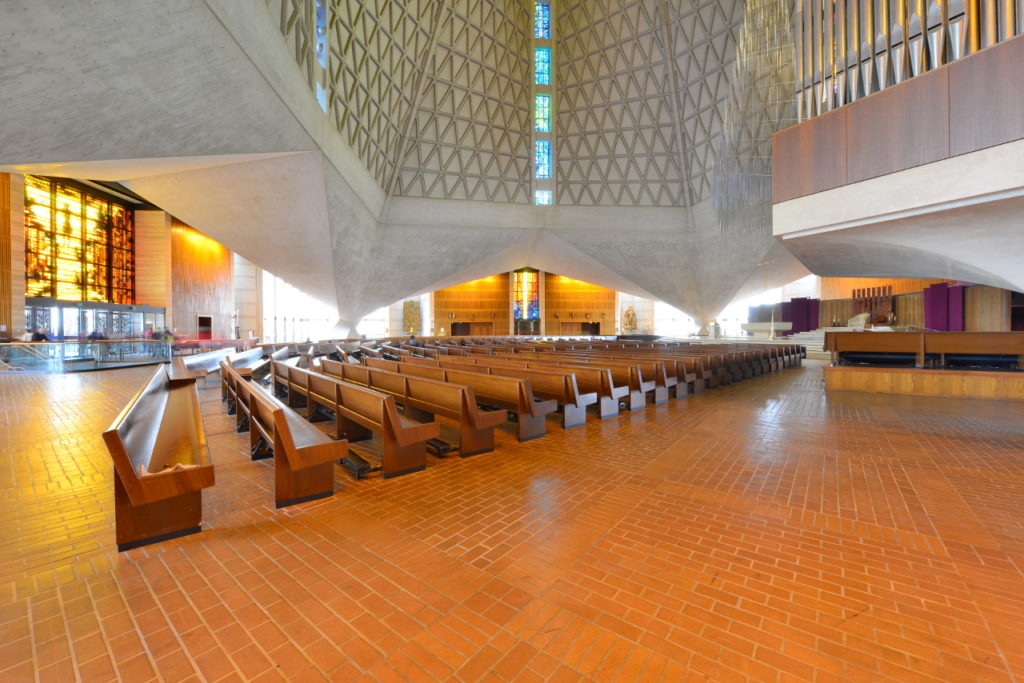

A new liturgy emerged from the council that lasted three years: “the church must focus, the council must move towards unity and integrity.” The effects of this statement were both architectural and liturgical. The council recommended that the new churches focus on unique and unobstructed spaces, where the sanctuary, the nave, the baptistery and the narthex can join. The effect of these design standards was expected, would unite the congregation and the priest. Although it precedes the board of directors, Belluschi’s design was adjusted to liturgical changes. The independent altar of St. Mary is slightly elevated, surrounded on three sides by congregational seats. The seats open outward so that no seat is more than 30 meters from the altar, and all are attached under the canopy of the bellicose hyperbolic paraboloids of Belluschi and Nervi.

Architectural design

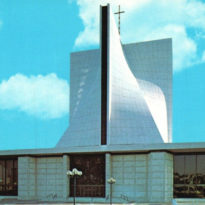

The contours of the new cathedral were clarified through a series of press conferences held in 1964. The surprisingly modern design that was presented was received with great recognition. Archbishop McGucken’s team of architects had clearly designed a cathedral equal to the greatness of San Francisco, and which, according to Nervi, was “The first cathedral truly of our time and in harmony with the liturgical reforms of the Council.”

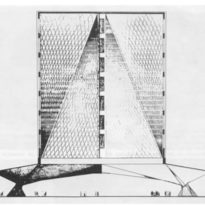

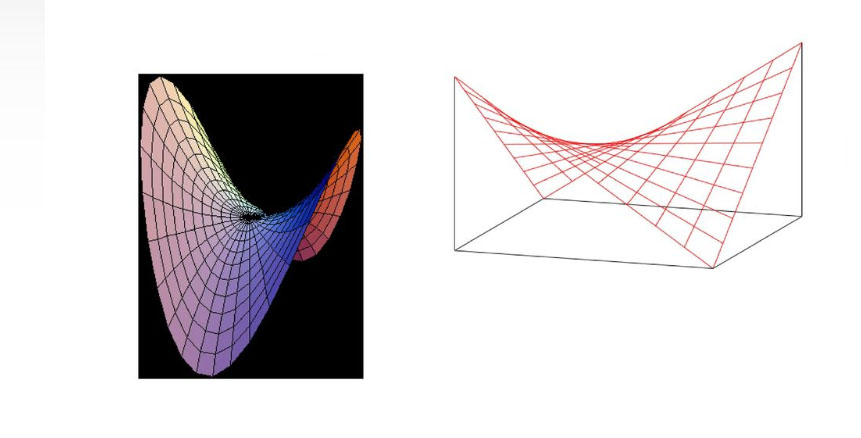

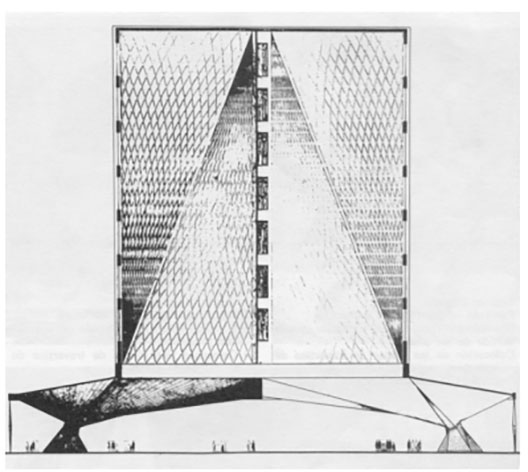

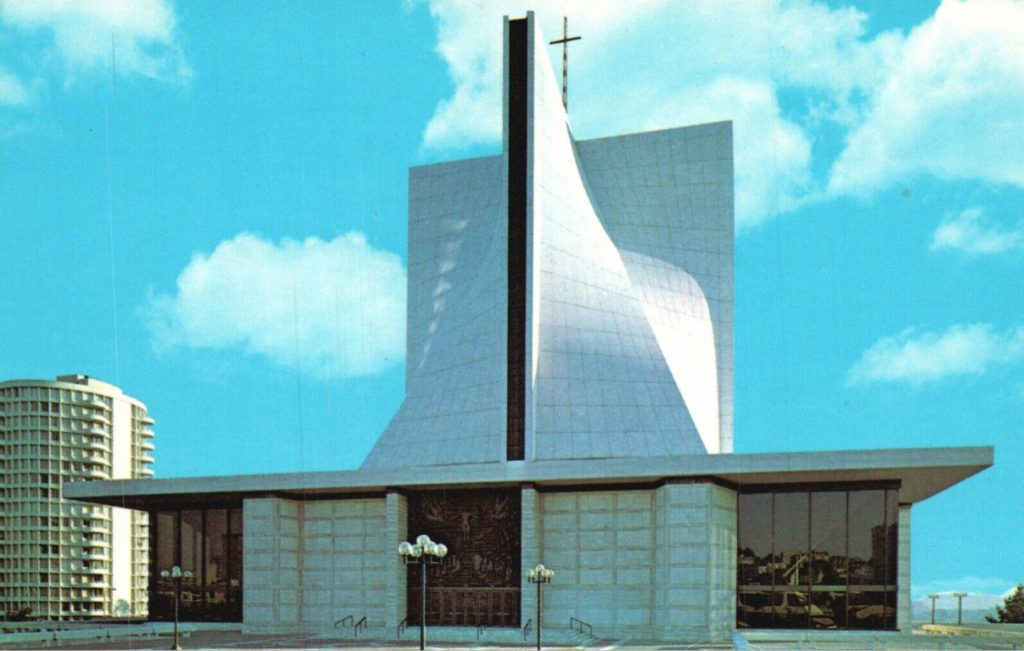

The striking design of the cathedral is derived from the geometric principle of the hyperbolic paraboloid, in which the structure curves upwards in graceful lines from the four corners that join at a cross.

Belluschi and Nervi produced a series of design models of which Nervi made several test models considered “daunting” by Belluschi. At the Istituto Sperimentale Modelli e Strutture in Bergamo, Italy, Nervi tested these models for their performance and appearance: some models tried to solve how the paraboloids would meet the requirements of the terrain, while others tested the effects of gravity loads and seismic activity.Nervi built a 1: 100 scale model for wind tunnel tests, also resin models at 1: 40 and 1: 37 scale for seismic tests and a large 1: 15 scale model in reinforced concrete for gravity loading tests These experimental tests allowed the engineer to develop a level of design freedom by developing new limits and shapes Through these tests, Nervi determined that, both to accommodate settlement requirements and for stiffness In the building, the paraboloid structure would have to be reduced and placed on a larger square base. Nervi sent the resulting drawings to an American engineering company, where the design was tested in the digital space with the STRESS software developed by MIT.

It is not clear to whom the authorship of the building should be attributed. It seems that Belluschi developed the main design of the building, although some reports attribute Nervi most of it.

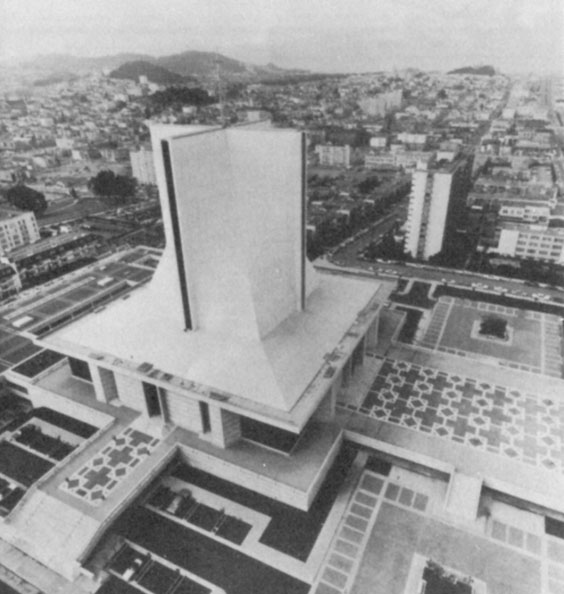

Spaces

The building stands on a 75x75m square floor that rests on an elevated base that contains a meeting room, a rectory and a parking lot. Inside the temple the plant is distributed in a cruciform church (Greek cross) of equal arms from the center with an address dominated by the location of the main accesses and the main altar. The remaining four corners are dedicated to secondary altars. The enclosure can accommodate 1200 attendees.

The access plaza has a floor whose design consists of basic shapes. Concrete pieces with diamond drawings in the center made of brick that in turn form brick crosses surrounded by a concrete circle.

Altar

One of the modifications resulting from the Second Vatican Council was that the altar should be turned so that the priest confronts the faithful. The altar of Sta María is austere and simple, a stone that stands on a platform surrounded by seats on three sides.

Organ

A large organ built by an old Italian firm from the city of Padua, Italy, Ruffati & Sons, who moved to the place to install it, is placed on an independent and sculpted pedestal.

Structure

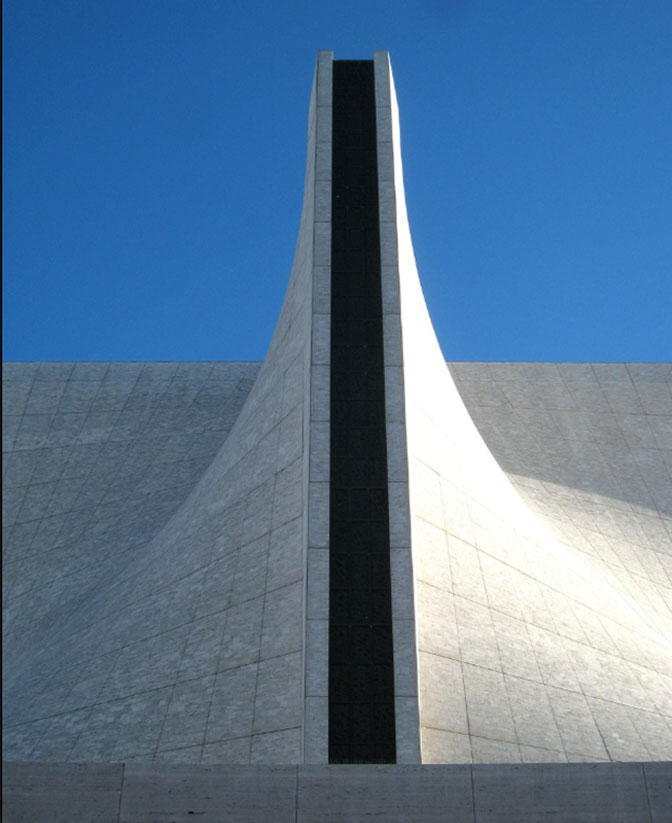

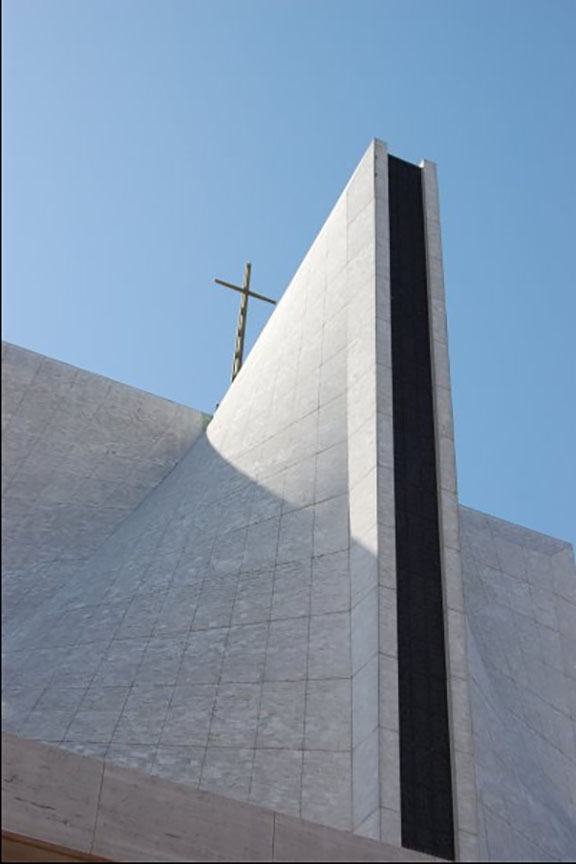

Eight hyperbolic paraboloids concrete coated in travertine hang from a 58m high steel structure. Hyperbolic paraboloids are doubly ruled surfaces shaped like a saddle.

In its upper part, the steel structure takes the form of the Greek cross. The thin paraboloids, with an average of 14cm thick, sweep down to finish. The building sits on a pedestal of bricks, limestone and reinforced concrete. The weight of this structure descends on huge hollow vaulted arches that contain steel armor. These arches sprout from four equally massive springs, tied by a prestressed cable to the ground, which narrow and then reinforce outwards.

The total height of the building is 57.91m, but when the size of the cross is added, the height is 74.68. The cross is 16.76m high.

Pillars

In the corners where the secondary altars are located, the four reinforced concrete pillars are placed on which the roof rests, both the lower and the upper part. In the corners the windows with views to the city of San Francisco are also located.

Each pillars with an irregular hexagonal base aligns with the diagonals of the square with an inclination that favors the trajectory of the forces. The capital is also hexagonal with an inclined plane towards the center of the building. In its narrowest part, each pillar has a circumference of 7.32m and 27.43m is embedded downwards in the bed of the rock.

Roof

The low-pitched roof is composed of hyperbolic paraboloid segments in a way reminiscent of the Cathedral of St. Mary of Tokyo, by Kenzo Tange, which was built in the early 1960s, such that the cross section Lower horizontal roof is a square and the upper cross section, which rises 58m from the ground, is a cross. It was resolved at two heights, a practically flat perimeter and another central concentric with the first.

Each of the faces that form this roof is born in one of the edges of the capital of the pillars on which they rest. At the same time, the inclination is so pronounced that it seems in itself a capital on which the central vault is supported, which is what forms the cross. The roof is crowned by a 17m high cross.

The upper part of the roof is formed by two paraboloids defined by two equal and symmetrical warped quadrilaterals in relation to the low deck plane. These intersecting quadrilaterals form the cross that crowns the building, turning each half of the square into one of the arms of the cross, which are joined with bands of colorful stained glass that stand out with sunlight. The hyperbolic prestressed concrete arches of the great Greek cross-shaped dome are a masterpiece of steel and concrete. Inside they are formed by 1680 prefabricated triangular pieces with 128 different sizes that transfer the entire weight of the structure to the ground.

Materials

Reinforced concrete and steel were used in its construction. The concrete was poured into the formwork mounted for the construction of the pillars, formwork whose form was made following the straight lines of the ruled of the warped quadrilaterals. The formwork ribs were placed on the outside of the formwork so that once the surfaces were removed they would be smooth and without marks.

Externally the arms of the cross are covered with rectangular travertine marble plates whose joints follow the direction of the straight lines of the paraboloid that forms the cross.

Inside the surface of each warped blade is defined by the texture of the various triangular shapes that form it and whose ribs strengthen the thin surface while remembering the Gothic style. The thin and hyperbolic paraboloids are composed of four layers, two layers of precast concrete molds, a pneumatically sprayed gunite layer and an outer layer of white travertine cladding tiles. The red brick floor of the cathedral recalls the ancient architecture of the Mission and the rich heritage of the local church.

Stained glass windows

Each of the four sides of the dome of the church has stained glass windows of György Kepes that continue until the culmination of the Greek cross. Sunlight shining through the stained glass windows and the perimeters of the structure help to illuminate the interior areas of the church and less use of electricity.

Belluschi brought Kepes, who was then a professor of visual design at MIT, to the project. The designer, who was interested in the psychological effects of light, had organized the exhibition “Light as a Creative Medium” at Harvard in 1965. Although Archbishop McGucken asked Kepes to include the symbolism in his design, Kepes insisted that the windows would remain non-figurative and that their effect, the emission of light fields, would have priority over their content, although it allowed an element of symbolism: the west window is red to represent fire, the gold of the south to represent air , the blue of the north to represent the water and the green of the east to represent the earth. Above, the Greek cross is represented in amber.

Hanging from the amber cross is the 36.58m high baldacchino by Richard Lippold, which suspends 14 levels of triangular aluminum rods with a fine gold wire and in whose center a gold crucifix also hangs.

Video