Allegheny County Courthouse

Introduction

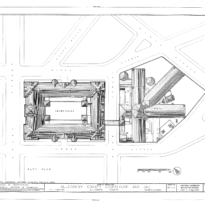

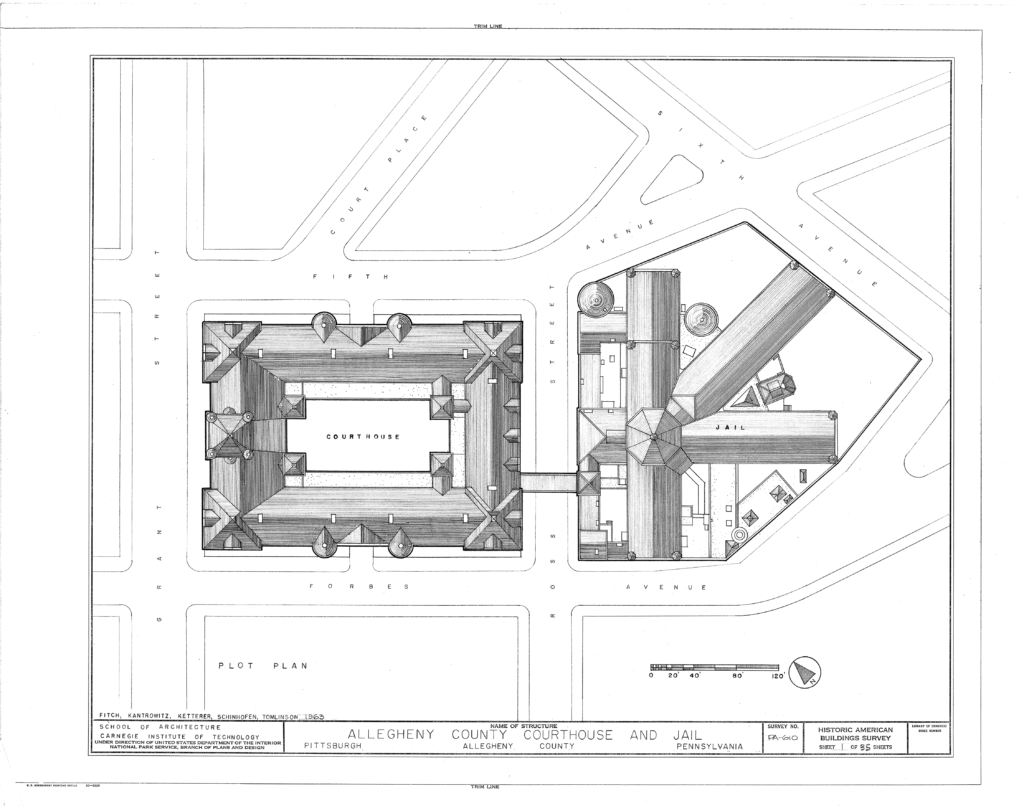

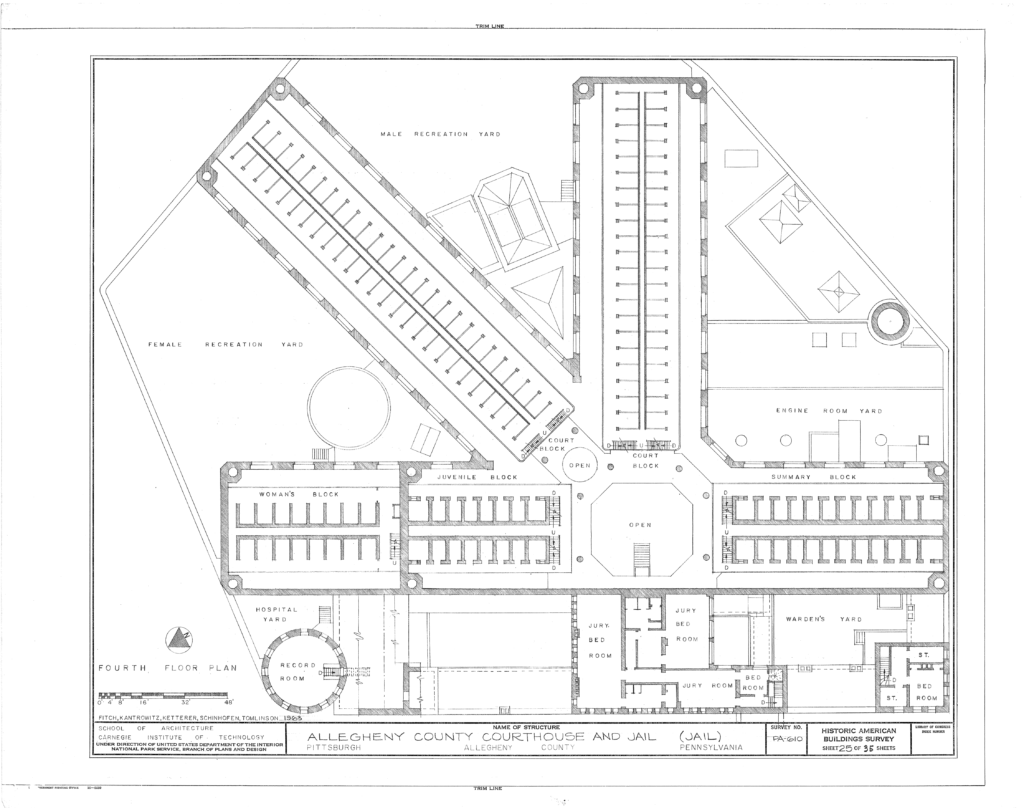

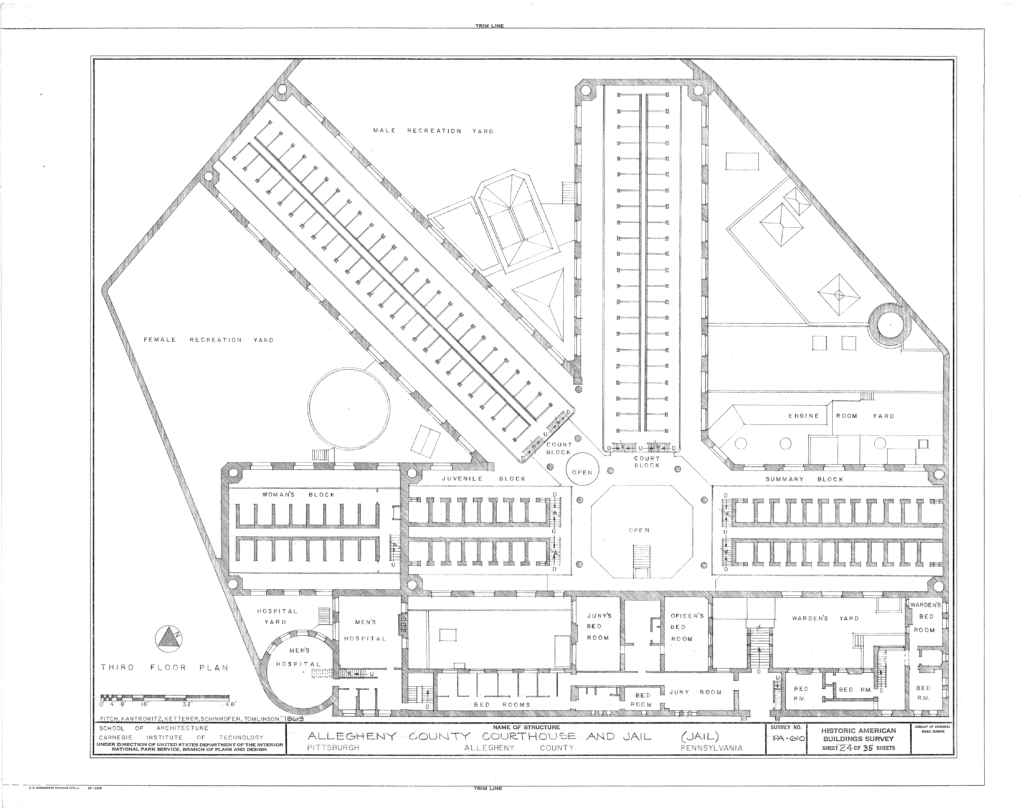

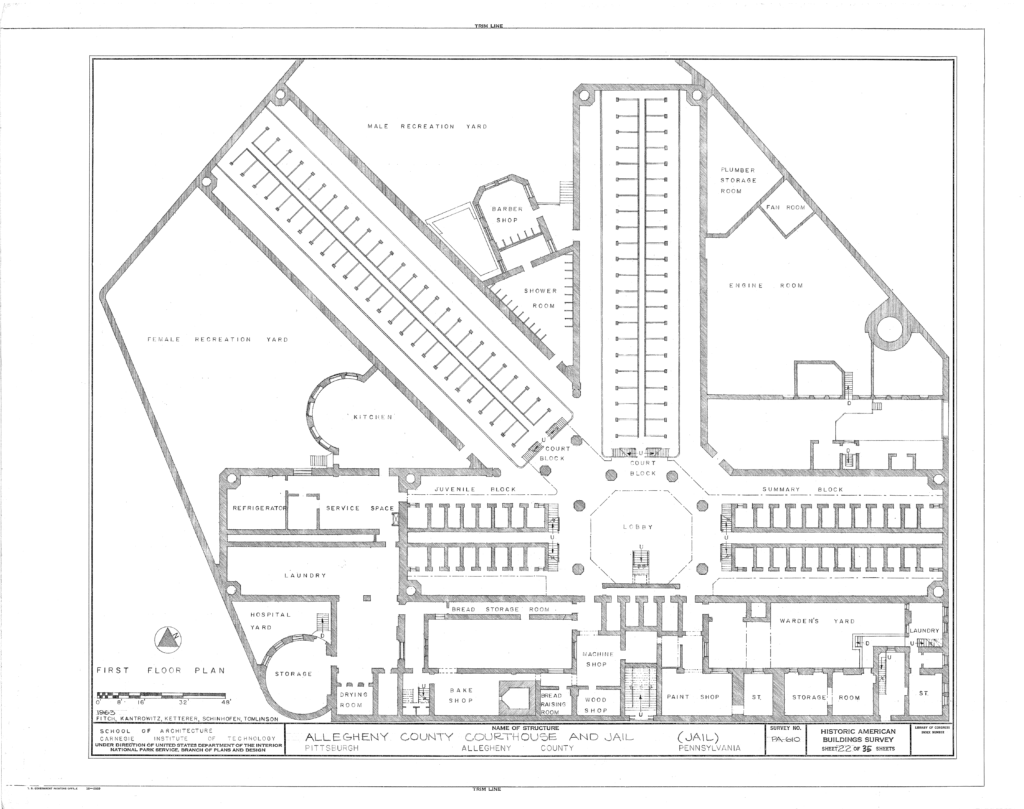

The original courthouse was destroyed by fire in 1882. The following year Richardson won the competition to design its replacement. His design comprised of two parts: the courthouse in the front, and the jail, linked a bridge, in the rear.

Location

436 Grant Street, Pittsburgh, PA

Concept

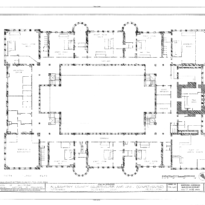

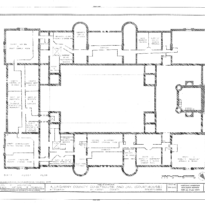

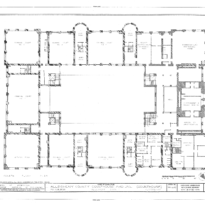

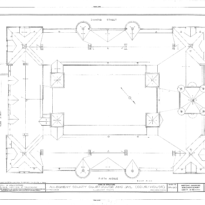

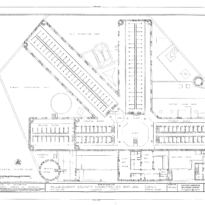

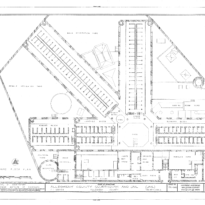

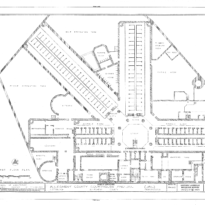

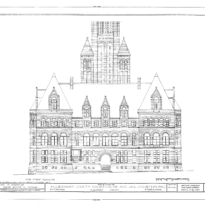

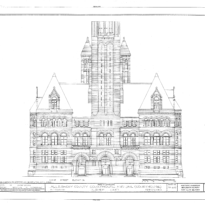

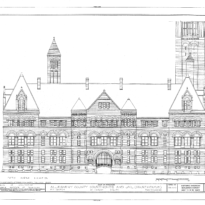

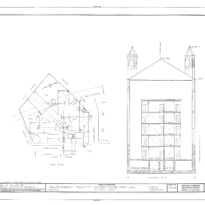

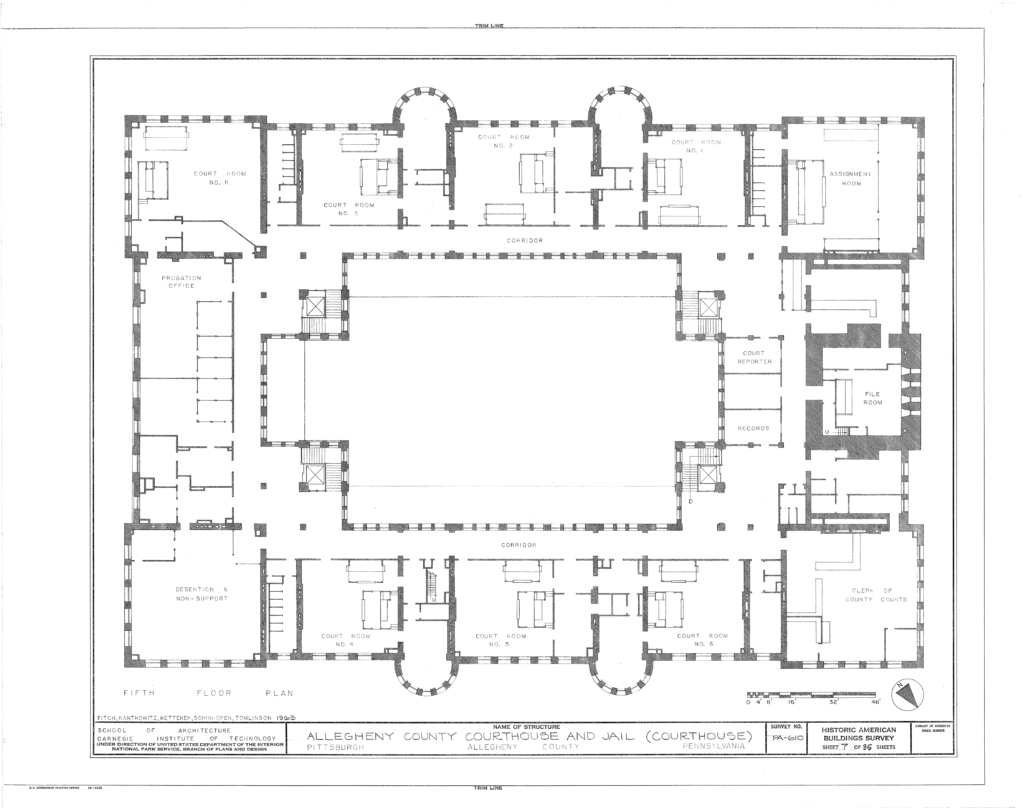

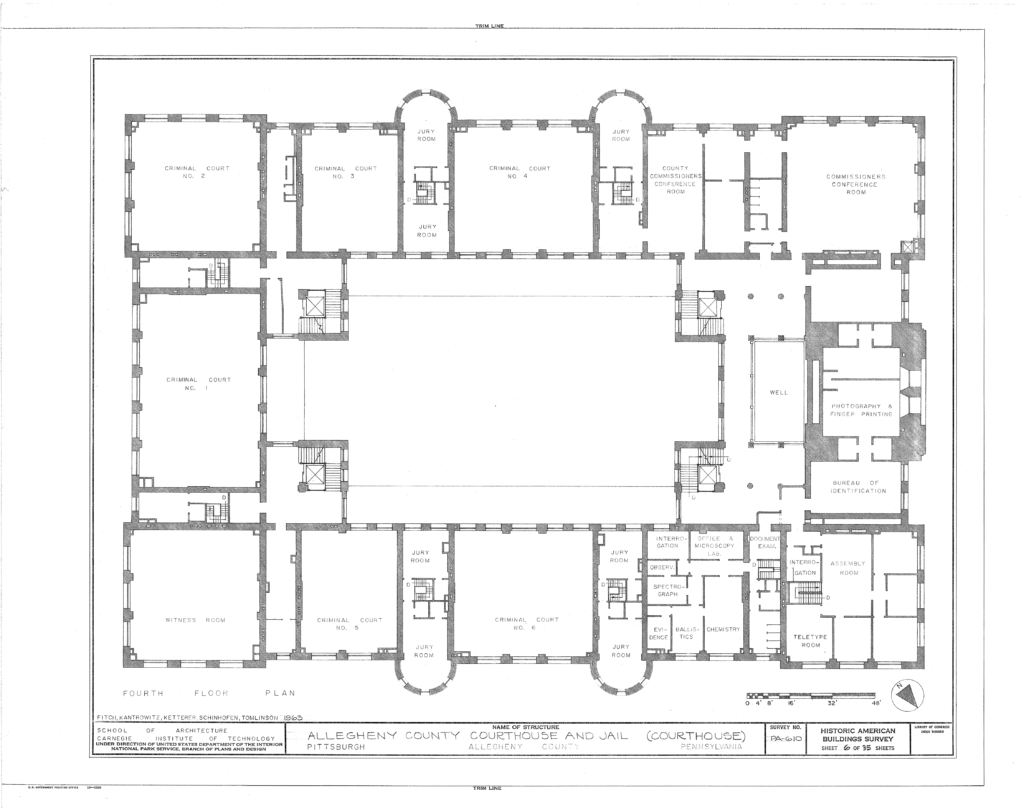

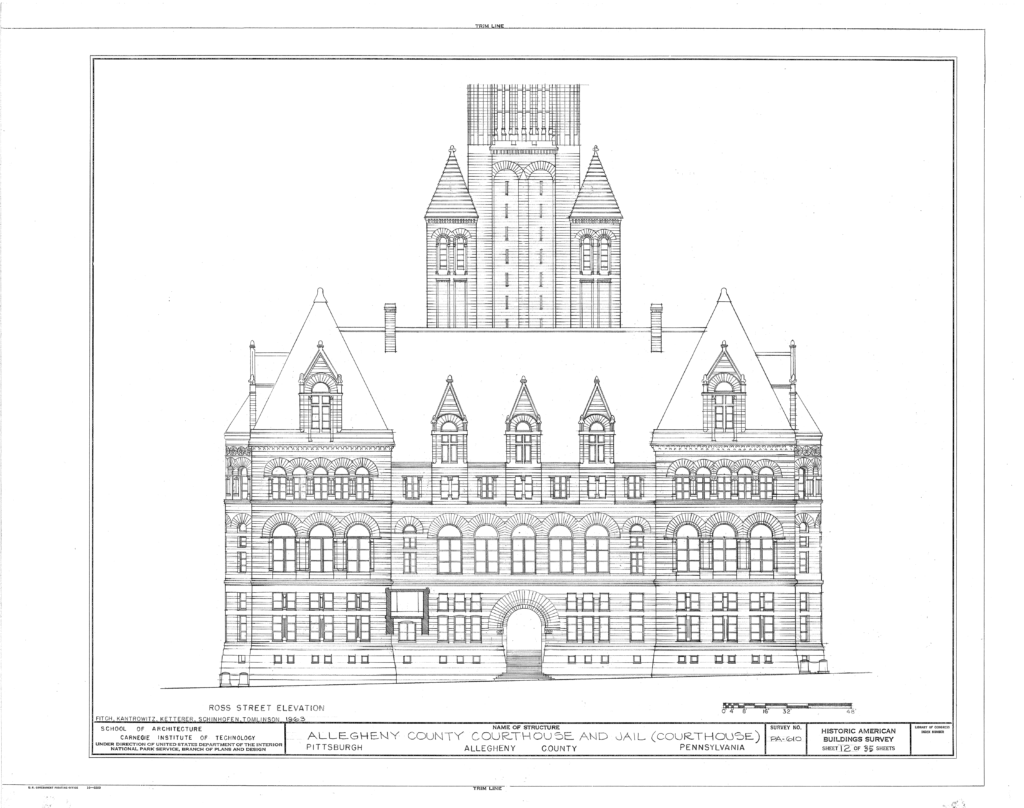

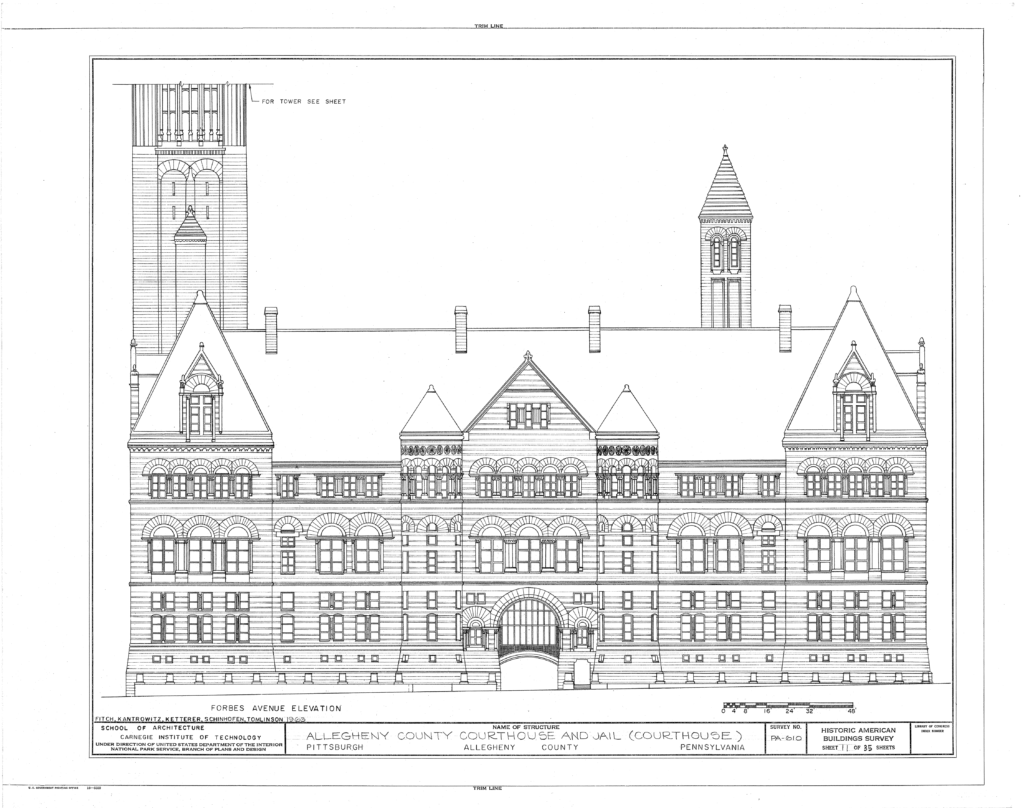

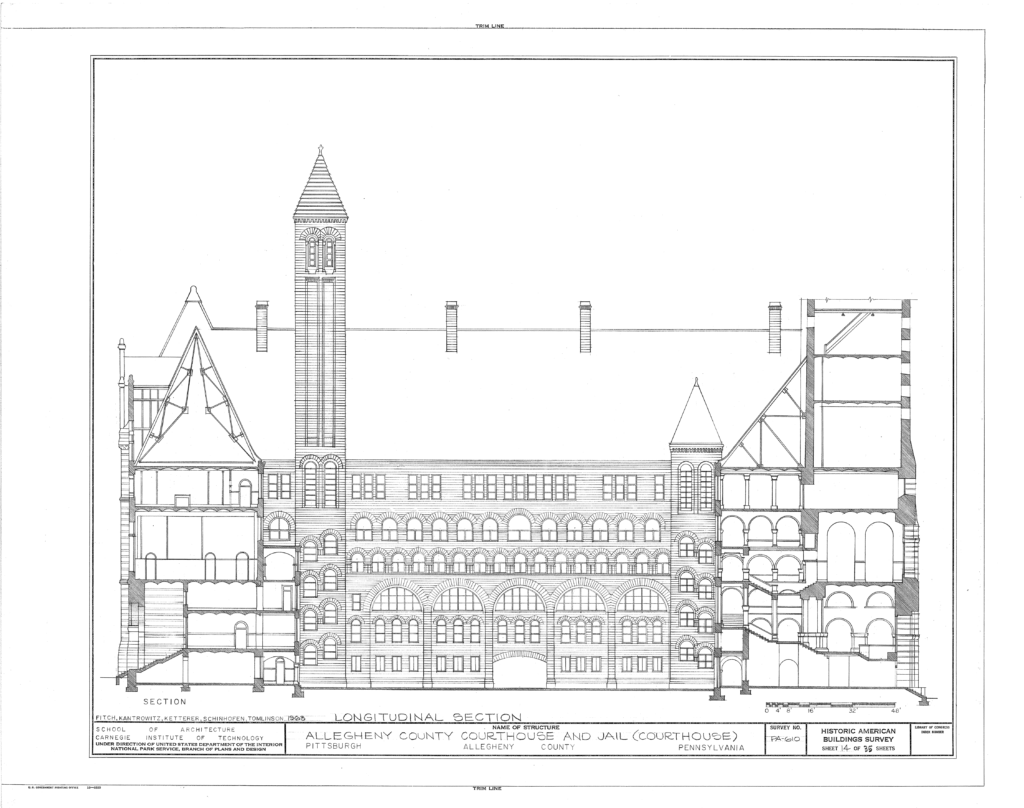

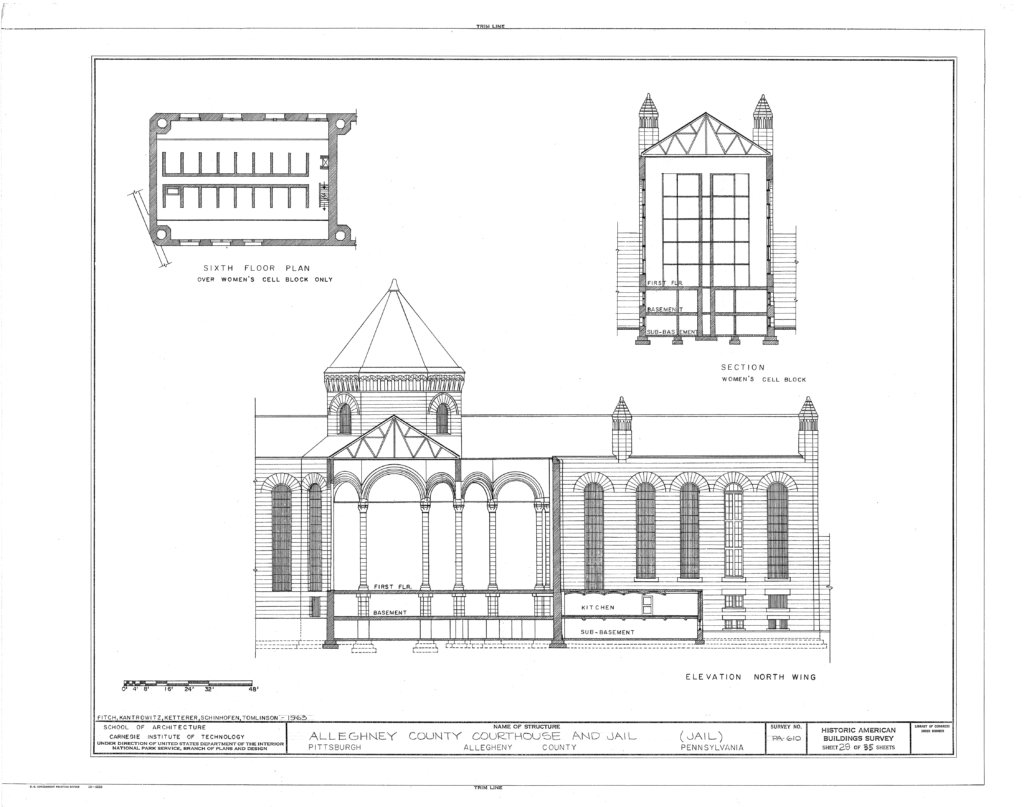

Similar to the earlier designed City Hall of its sister Pennsylvanian city, Philadelphia, Richardson chose a hollow, axial rectangular scheme enclosing a 70’ x 145’ courtyard. He also echoed the Philadelphia building by placing a center bell tower in the front of the main façade. The building has four floors of a single-loaded corridor with courtrooms that ring the exterior perimeter. The corridors line the courtyard.

Spaces

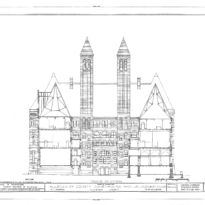

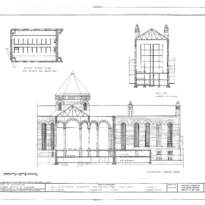

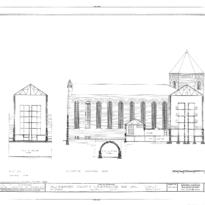

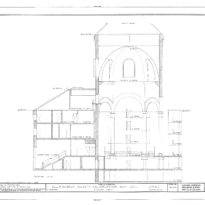

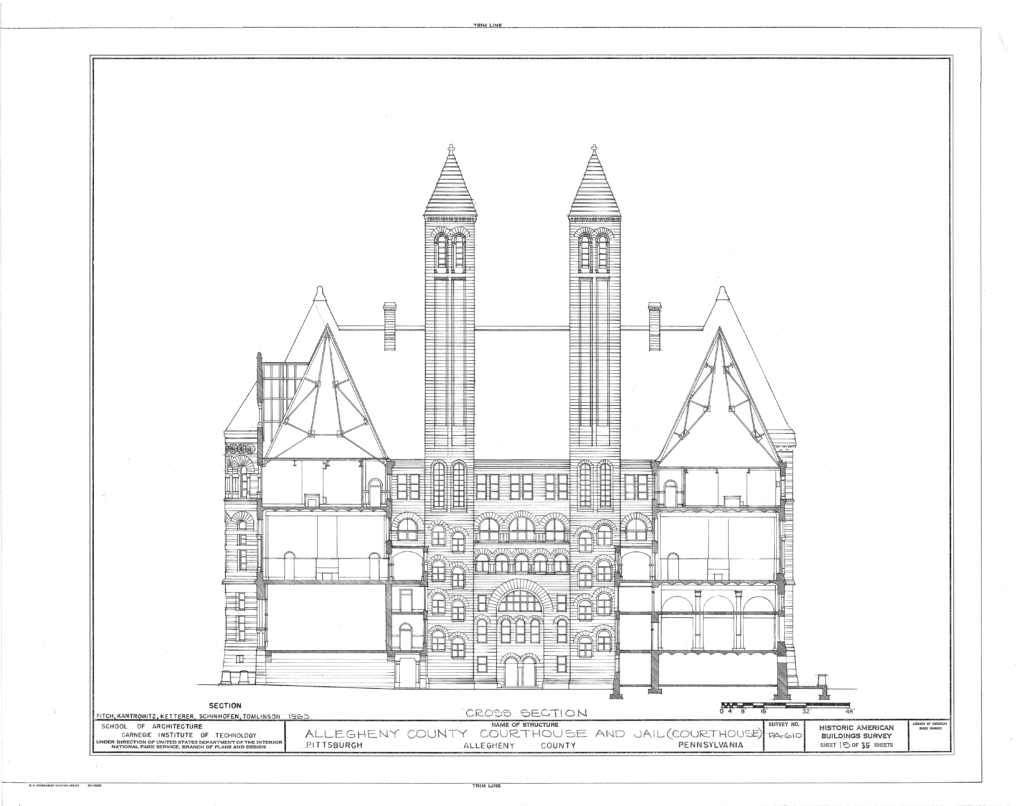

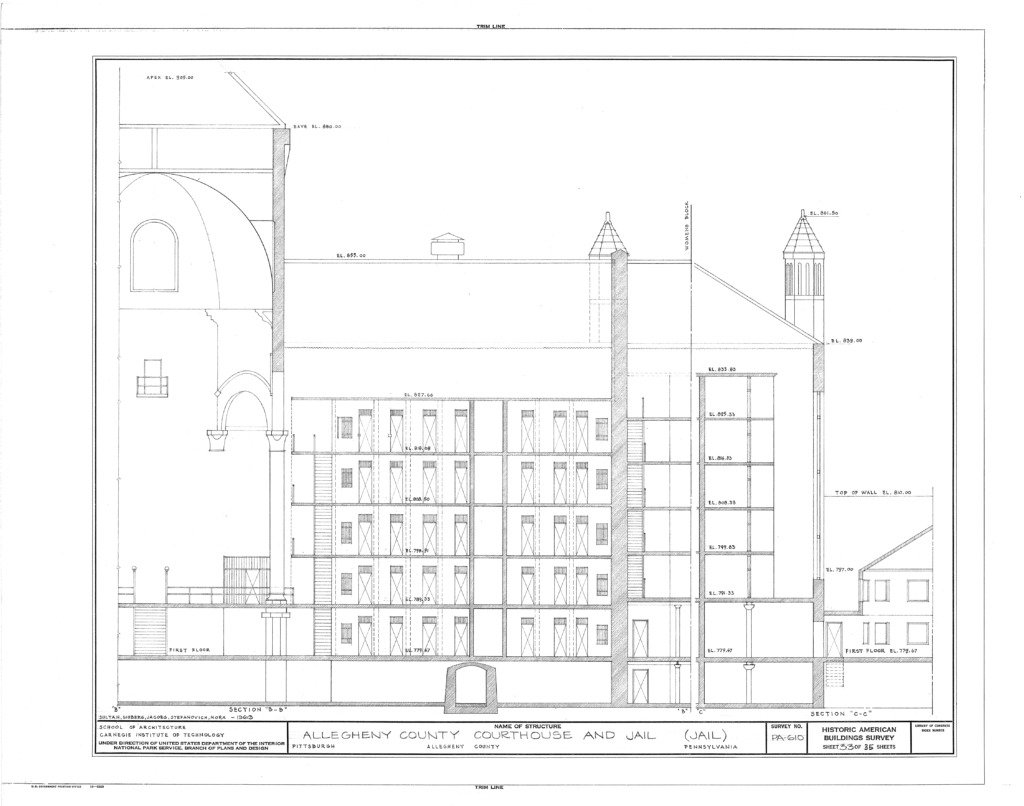

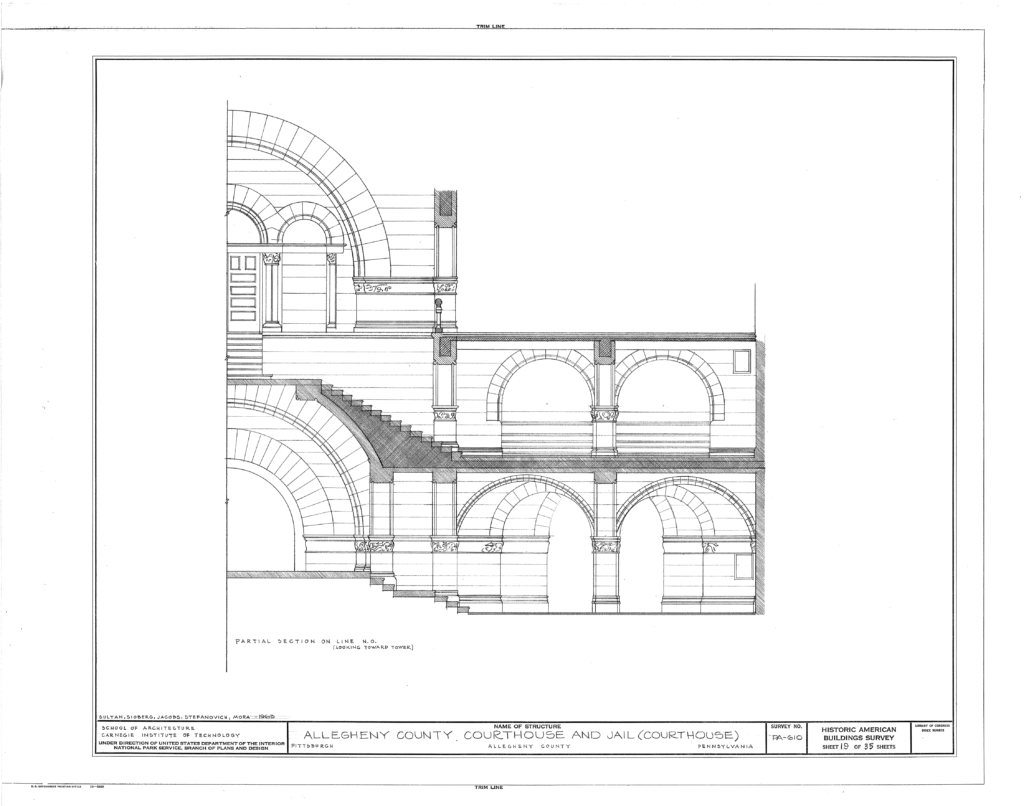

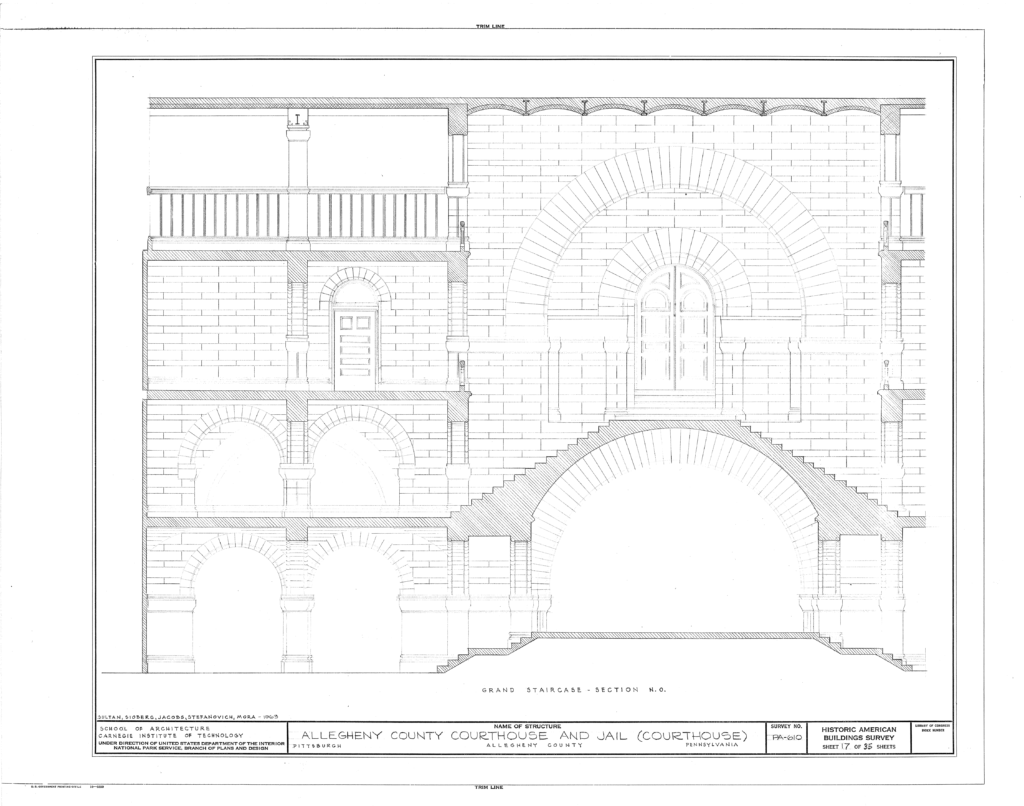

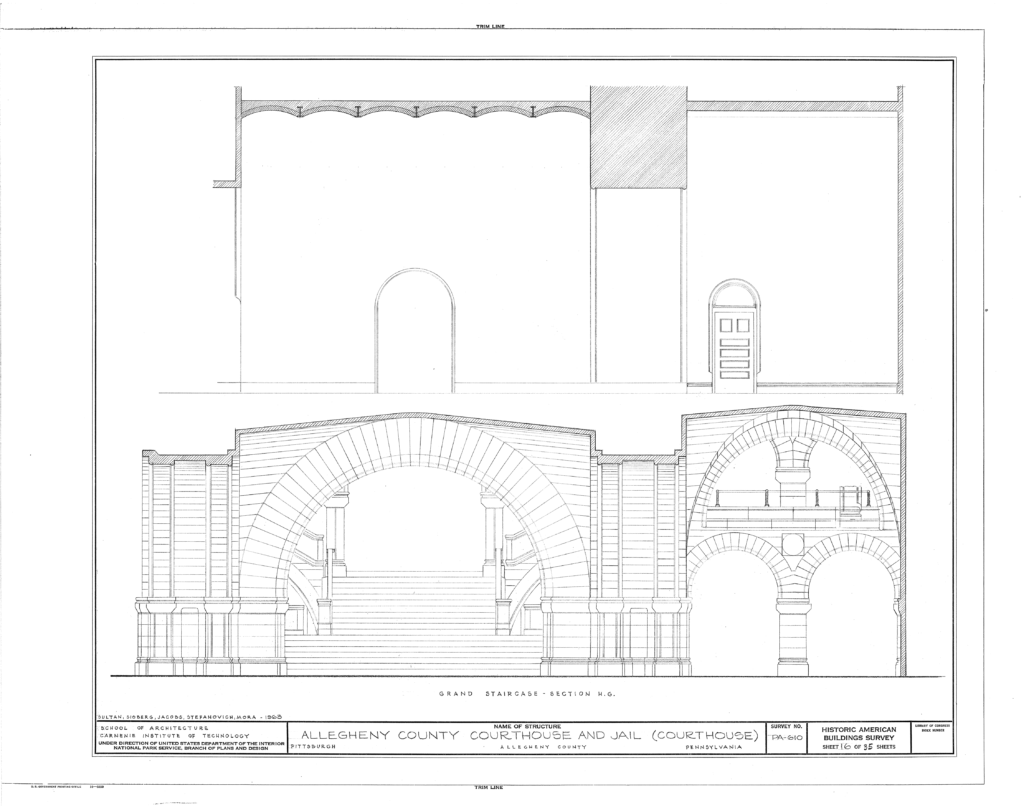

One enters the building through one of three monumental triumphal arches, one in the middle of the tower’s base, and one to either side of the tower into a Piranesi-esque grand stairway that leads to the courtroom floors. The courtrooms are double-height spaces, allowing an intermediate floor of smaller spaces to be placed where practical. This height allowed the courtrooms to be daylit from both sides because a row of windows to provide daylight from the courtyard are located above the shortened height of the corridor ceilings.

Materials

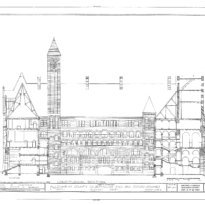

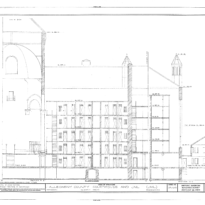

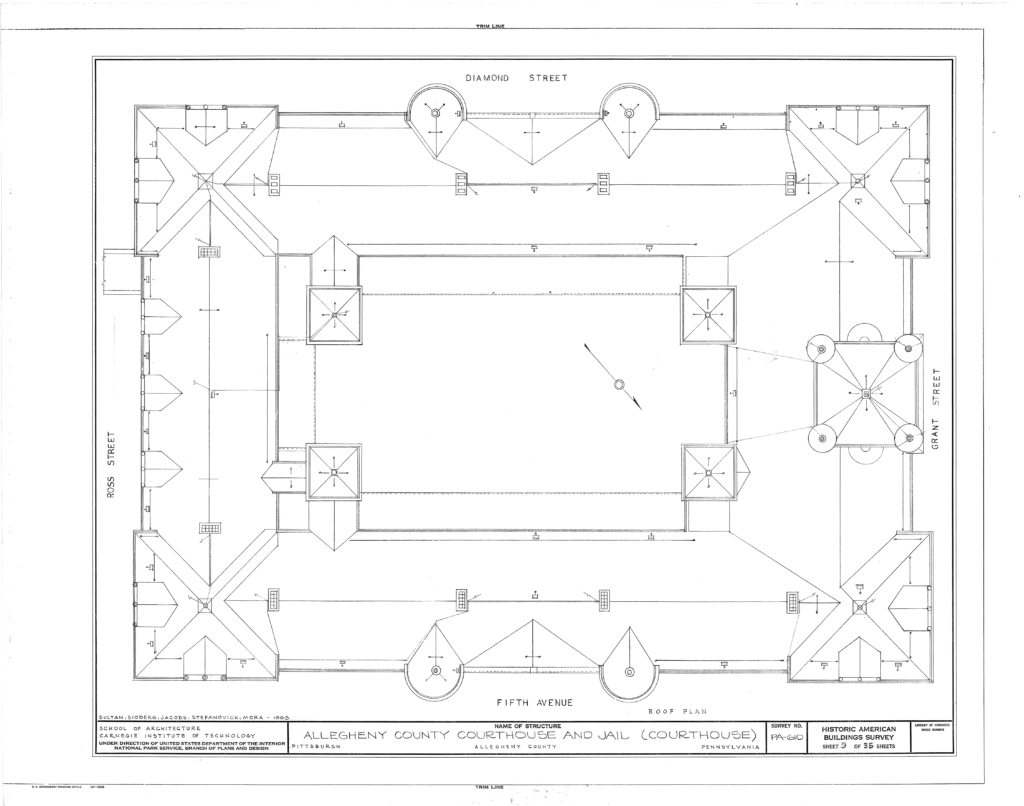

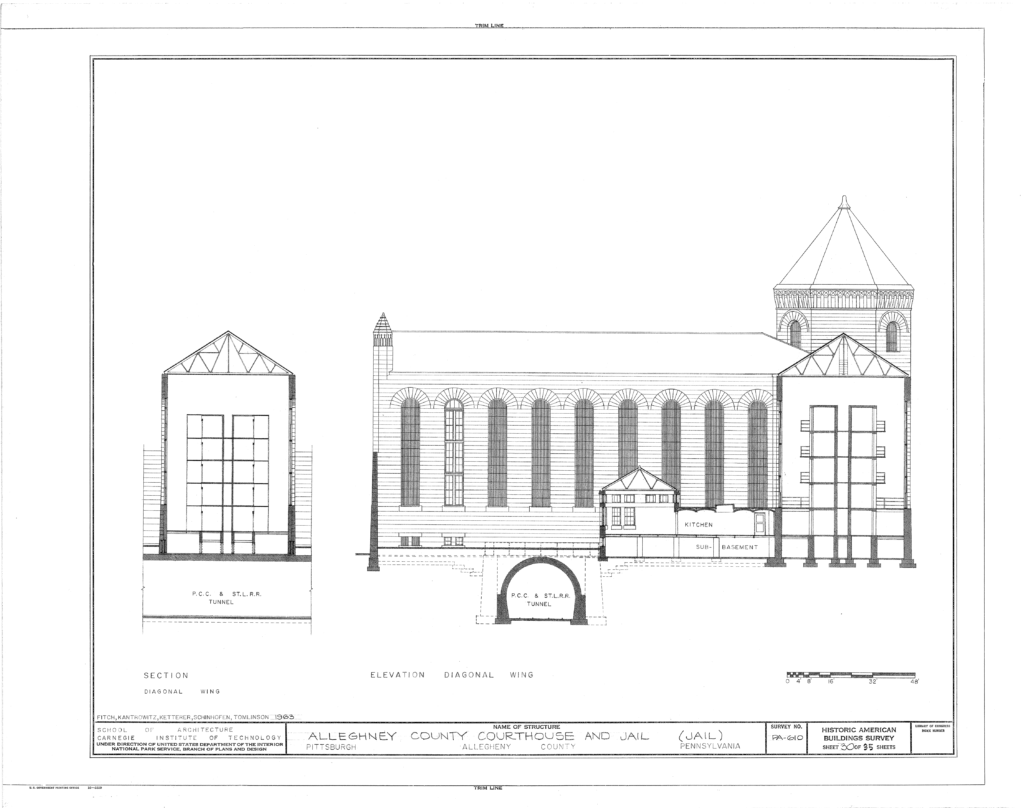

To order his massing of the complex program, Richardson chose a symmetric courtyard plan in which he emphasized the four corners with pavilions that project from the body and the roof of the building. He also expressed the entrance on each of the building’s long sides by projecting the semicircular stairways that frame these entrances. The building is duly famous for Richardson’s design of the exterior pink Milford granite rock-faced ashlar walls with red mortar in which he alternated the height of the coursing between narrow and tall courses. As this building was designed following his return from his European tour in 1882, historians have noted his post-trip tendency to abandon his once-trademarked polychrome palette of a light stone body with dark stone detailing in favor of a more reposeful monochromatic body. The elevation he articulated into a series of four horizontal layers; base, courtrooms, upper cornice, and high-pitched roof. He used red terra cotta tiles to cover the buildings various roofs.

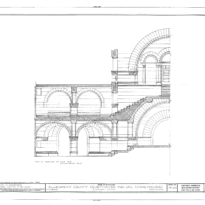

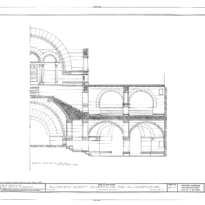

While he treated the exterior elevations in a conventional, i.e., formal, manner, Richardson’s post-Europe interest in evolving a truly individual, modern American style is very evident in how he designed the courtyard elevations. All carved figural ornament has been eliminated. These surfaces consist only of rock-faced walls with the voids for the windows formed with arches with oversized voisssoirs. The courtrooms on the two long sides are expressed as “aqueducts,” continuous arcades that are buttressed at each end by a staircase tower, whose function is expressed with the diagonally aligned windows. (Note that by pushing the stairs into the courtyard, he was able to maximize the use of the floor area for programmatic functions.) The clerestory windows above the corridors are located directly under the main arches, while the lower corridor is expressed as a three-arched arcade inserted within the piers of the main arcade. The courtyard elevations have achieved a meaningful, architecturally-powerful, ahistoric aesthetic without the use of any historic ornament. One could say here is evidence that Richardson was on the verge of achieving his goal of developing a modern, American architecture for the time he was living in.

Structure/Mechcanical

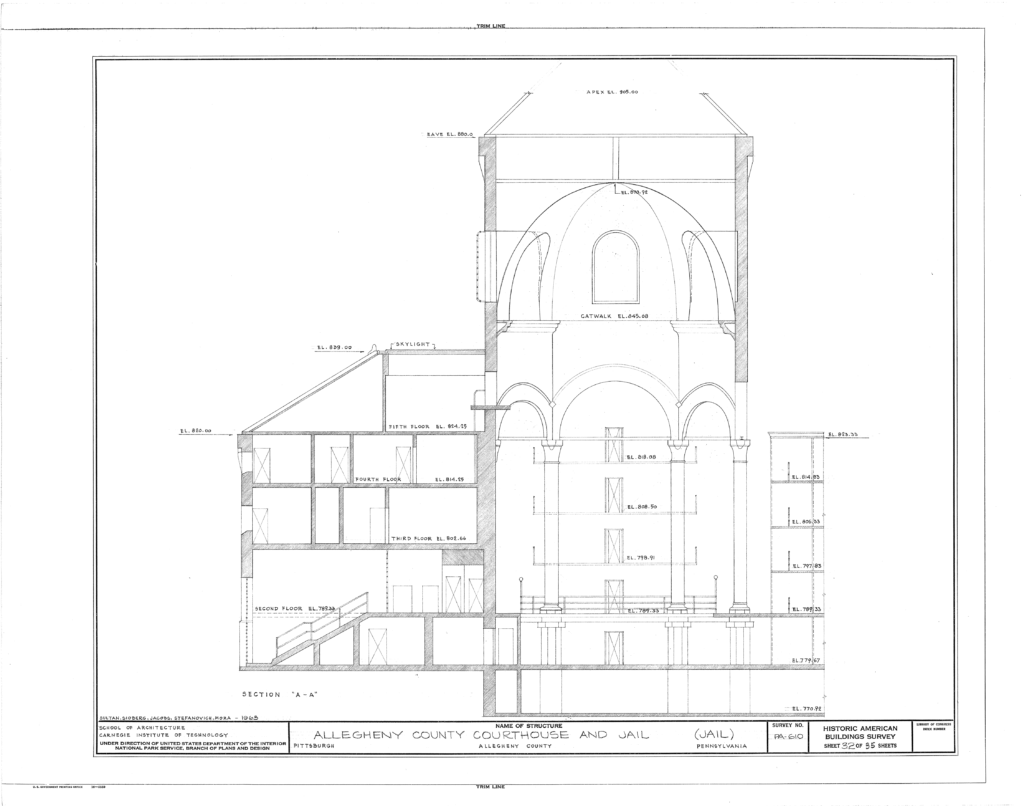

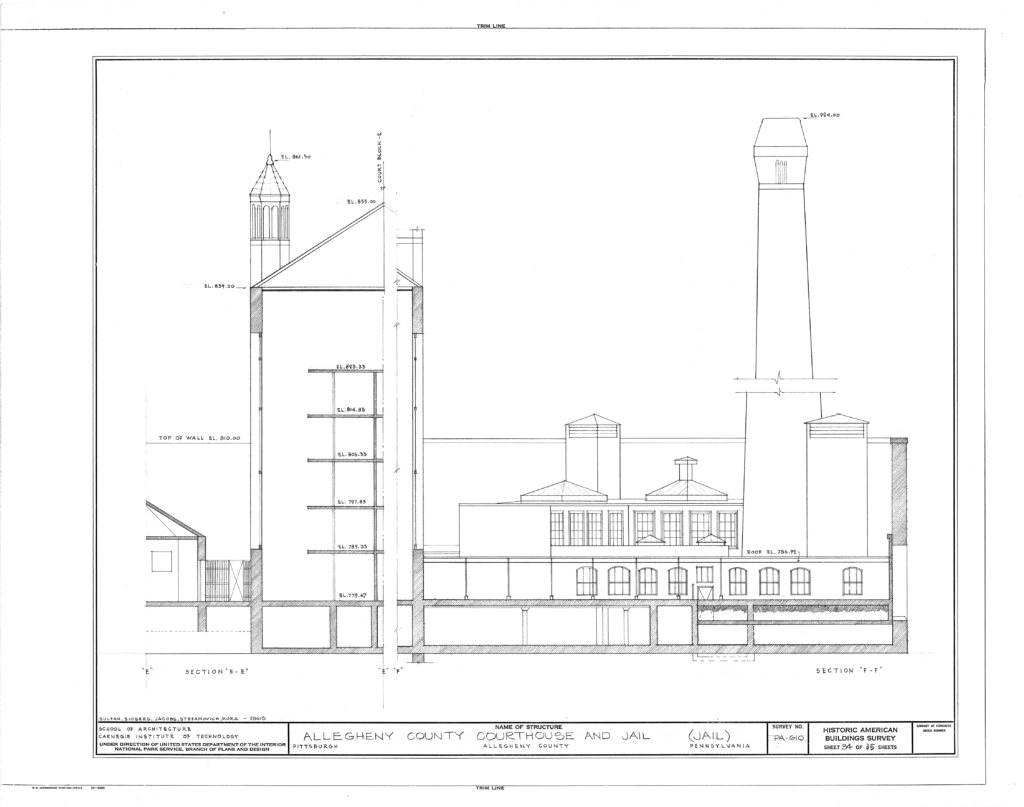

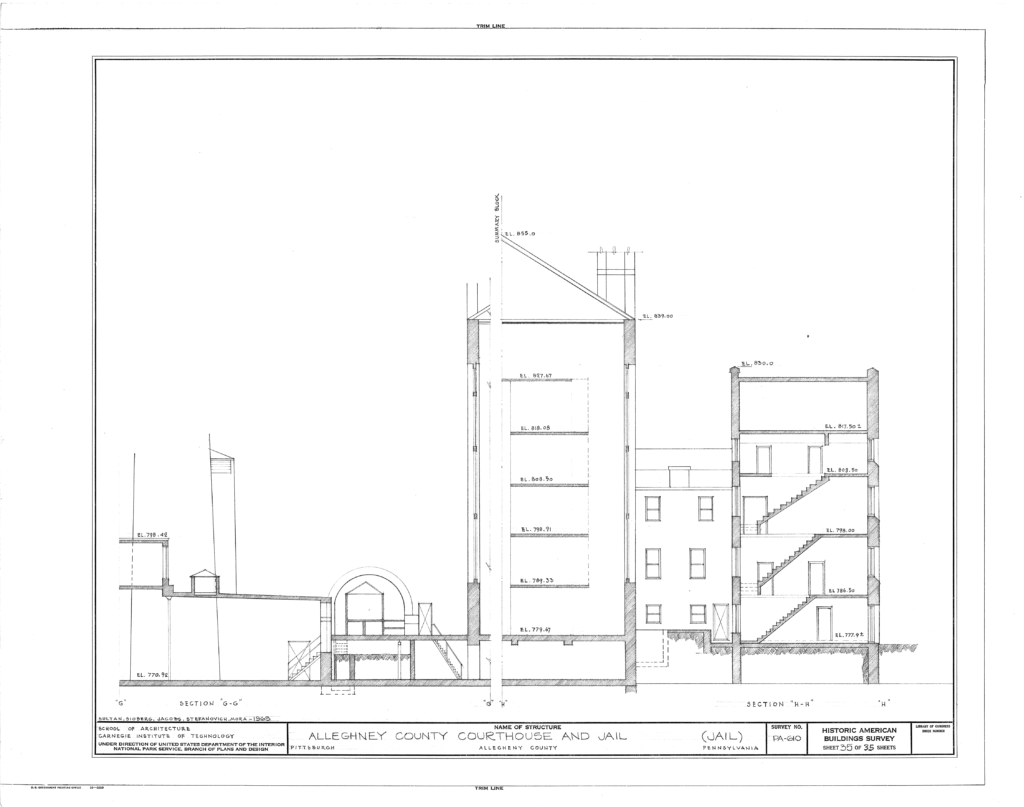

The 249’ tall tower had a very functional purpose, in addition to marking the building’s location in the urban landscaper: by reaching as high as it could, it was trying to extract the freshest air available in Pittsburgh’s steel industry-polluted environment. Intake vents in the upper portion of the tower pulled air into the ducts that brought the air to a conditioning system located in the basement. From here it was then distributed throughout the building, with exhaust air being vented through two shorter towers located at the rear of the courtyard, on axis with the front tower.

Richardson gave the tower an appropriate unbroken vertical expression to balance the horizontal base. This he achieved by detailing each corner as a curved turret, thereby avoiding the formation of a sharp corner that allowed an observer’s eye to continue around the corner without interruption. He then detailed the elevation of the field that stretched between the corner turrets as a hierarchy of arcades that began with the monumental entry arch in the ground floor; then doubled to two arches in the second level. Above the base of the tower, the body of the tower started with the same dual arcade, albeit it was blind to permit the storage of records. It then turned into a three-arched arcade that was capped with a range of four single-story high arches. A very tall, pitched roof topped off the uncompromising vertical. Richardson complemented the geometrical progression in the number of arches at each level by creating a sense of false perspective, that further enhanced the verticality of the tower, by increasing the number of floors in each layer: the lowest, 2-arched portion extended for 10 stories; the middle, 3-arched portion extended for 4 stories, and the upper, 4-arched level extended only one story. The vertical push into the sky was reinforced with a turret and conical roof placed on top of each corner cylinder.